The group of young people, probably my age, wears matching black and red T-shirts. The backs read, “Building a better future” in bold, white letters. They stand in a row, arms around one another, grinning, laughing, chatting in English, while posing for a group picture. The background of this photo: the thousands of pointed white headstones of the Srebrenica Genocide Memorial.

I follow silently behind Beba, fuming at the appalling indifference of this group. Beba, thankfully, seems not to notice as she walks slowly among the countless rows of graves, surely recognizing names and remembering friends. As I kneel on the grass to photograph one of the headstones, I become acutely aware of the fact that someone’s body lies beneath me. It’s as if I can actually feel the bones crunching under my feet. I read the headstone. This person was born the same year as my mother. In July 1995, my mother was seven months pregnant with my baby sister. In July 1995, this person was slaughtered and thrown into a mass grave in an effort to wipe out an entire group of human beings.

The anger I feel while standing surrounded by pink flowers and white marble is not wholly surprising to me. I often joke when people ask me how I do not get depressed studying genocide as a full-time career and say it’s because it makes me pissed off, not sad. Wanting to scream at these unmoved “Future Builders,” who’s laughter seems to echo off the surrounding hillsides, I find this suspicion I’ve had of myself is confirmed.

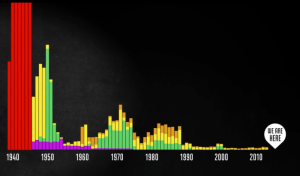

I recently watched a video (above) illustrating the death tolls of different groups, soldiers and civilians, during World War II. The sleek animated infographic shows the magnitude of the human cost of the war, including the Holocaust. At first, I was impressed. What a simple and effective way to show the perspectives of lives lost. I had never realized just how many Soviet soldiers had perished, nor what an astonishing proportion of Holocaust victims were from Poland. However, I became apprehensive as the narration described the Japanese as losing “only” 200,000 in the invasion of China and didn’t even include a bar to show the homosexuals, Catholics, and disabled killed in the Holocaust because it was “relatively small.”

A screenshot of “The Fallen” by Neil Halloran, comparing battle deaths from WWII to conflicts in following years.

My apprehension turned to frustration as the video zoomed out to show the looming bar of millions of battle deaths in World War II compared to soldiers killed in subsequent conflicts. The 1990s, containing the Rwandan and Bosnian genocides, where civilian deaths far outnumber military ones, become mere blips on the radar of the 20th century. Nevertheless, the video’s creator, Neil Halloran, argues the world is becoming more peaceful:

“We give such importance to the word ‘peace,’ but we don’t tend to notice it when it occurs or report on it. Sometimes it takes reminding ourselves of how terrible the world once was to see the peace that has been growing around us.”

I am not disputing the data presented in this video, but its conclusion that since there are less deaths in the last few decades than in World War II, the world, especially the “Great Powers” should give themselves a pat on the back, is dangerously misguided. Certainly, I am glad that there are less deaths now than in the 1940s but I fear this comforting rhetoric moves people to complacency.

The names of those killed engraved in stone.

I stand surrounded by graves of innocent men and boys and think, this is not what peace looks like. I think back to September 11, 2001, when 2,977 innocent people died in the blink of an eye and the thousands that followed on all sides in the wars to follow. I think of the 202,354 dead in Syria. The 2,000 killed in a single day in Nigeria by Boko Haram.

In comparison to WWII, entire civil wars and genocides become statistically insignificant. And I wonder to myself, how could we let this happen? When in the last 70 years of “never again” did we create the equation that peace equals less than x number of deaths?

I watch the “Future Builders” cheerfully climb into their fleet of mini vans, uploading their group photos to Instagram and preparing for the next item of their itinerary and I wonder how many more bodies need to be buried under this blood-soaked soil to stun us into silence. How many years passed does it take before a graveyard becomes a tourist attraction? How many miles must lie between “us” and “them” before we are moved from apathy to action?

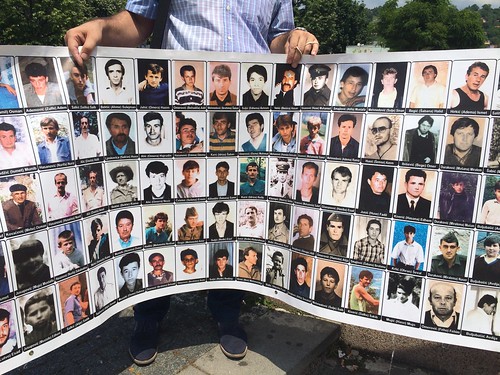

At a monthly protest in Tuzla, families bring banners depicted the faces of thousands lost in the Srebrenica genocide.

We can quantify bodies and put them on a graph but in doing so we lose the ability to comprehend the unquantifiable: the anxiety of waiting decades for your loved one’s body to be found and identified; the trauma of knowing how they were brutally murdered or, perhaps, the nightmares of not knowing and forever wondering how it happened; the oppressive quiet surrounding destroyed houses and empty schools; the countless family photos lost as families fled their homes with every intention of coming back.

I am not innocent of this kind of distanced thinking I describe here. At one point, I find myself noting that this gravesite is smaller than I expected, comparing it to the massive Arlington Cemetery back home in Washington. There, headstones go as far as the eye can see, but here, if I stand back far enough I can just make out the site’s perimeter.

And then I remember my friend back in Tuzla, Zifa, who will finally lay her son-in-law’s newly identified remains to rest here next month alongside her son, brother, and nephews. There is simply no acceptable number of deaths. Even just one is far too many.

Posted By Sarah Reichenbach

Posted Jun 15th, 2015

2 Comments

emily w

June 29, 2015

Wow, what a powerful reflection Sarah. It is certainly easy to look at victims of mass atrocity as merely statistics and numbers. It is more comfortable to speak about mass atrocity in academic terms, because once we begin to consider the lives behind the numbers, it almost becomes too painful to bear. When we think about the impact of just one life lost — the impact on family, friends, community, the missed opportunity of a life long lived, and basic human existence and contribution to life on this planet — then we really begin to approach the fringe of understanding the true cost of violence and war, and why we commit our lives to this work of preventing mass atrocity.

Artie

March 10, 2017

That’s really thinking at an imspvrsiee level