When we arrived at Lelmolok IDP Camp, the women and men were assembled, waiting for us. We learned that only about five families still live at the camp; most everyone else has been resettled back to their land. The people who came to speak to us had walked – some five minutes, some half an hour – back to the camp, and were now gathered under the sparse shade of the camp’s young trees. We met with the women first, Charles and Francis (Kenyan university students who lead the mentoring program) translating for us.

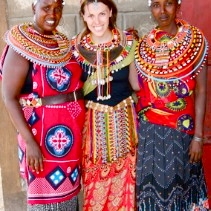

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Each woman told us her story of how she came to live in the camp, what her displaced life was like, and how resettlement was – or wasn’t – different. Here are two women’s lives, in brief: Susan and Margaret.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Susan is 28 years old, a mother of two, a member of the Kikuyu tribe, and was a farmer before the election violence. She used to grow cabbage, collards, and raise chickens. On the night of December 30, 2007, her farm and livestock were burned and her house destroyed. The following weeks were similar to that described by Beatrice in the previous interview – a week at the District Officer’s residence, then over to Eldoret’s cattle showground, and finally relocated to the camp. At first, Susan felt unsafe at the camp; local Kalenjins were restricting the Kikuyus’ movements outside of the camp’s boundaries, and threatening to harm anyone who strayed far from their tent. A reconciliation program was established in town, and it seemed to relax tensions for a time: Susan began to leave the camp during the day, even returning to her land for a few hours each day and farming with the hope that the next day her crops would remain untouched by her neighbors.

Susan and her family have resettled back to their land, but life has not changed significantly. Her family is still living in a tent, the same leaky one they had at the camp, and they do not have enough money to fully reinvigorate their farmland. Now that aid donations have stopped, it is essential that Susan grow most of her own food. She manages to grow collard greens and spinach, and has even started a local hair salon in the nearest town to earn an income. Her husband has taken on temporary work as a driver-for-hire, and between them Susan is hoping to have enough money to add more crops to her farm next season. That is, if the rains come (they are late) and the present crops yield a decent harvest to sustain them.

What you should know: the government gave most displaced families a one-time payment of 10,000 Kenyan shillings (about $130) to cover general costs during their displacement. This money was usually spent on food, bedding, and latrines for the camp. This money was not sufficient for rebuilding a home, since the average cost for a very basic home in Kenya is 50,000 shillings or, for a more permanent house (like many of them had before), around 150,000 shillings. Prior to May of this year, Susan’s family and others in the camp were receiving monthly aid rations as follows: 6 kg of flour per person, 2 kg per household of dry porridge, and one liter per household of cooking oil. I needn’t tell you this is not enough to live on, no matter how frugal a family, like Susan’s, tries to be.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Margaret is 56 years old, a single mother of five, and is the informal head of women at Lelmolok Camp (and Susan’s mother-in-law). Before the election violence, she was a farmer with a small business in town selling milk from her cows, vegetables from her farm, and assorted house products. Since being displaced, Margaret is limited to farming, and doesn’t produce enough to sell at the market. At the time of the violence, Margaret was living next door to her son and Susan. She heard commotion down the street and ran out of the house to see her son’s house on fire. Margaret and Susan, carrying Susan’s children and only what they had on, hid in a nearby field for two days, eventually reuniting with Susan’s husband. Margaret’s property – worth an estimated one million Kenyan shillings (roughly $13,000) – was turned to ash. Along with her belongings, Margaret had her children’s school certificates stored in the house. Without these documents, her children (ages 13 to 37) cannot get a job or continue schooling. When she went to the school for help, they printed a letter to serve as a substitute for the burned certificates – but there was a catch: these letters had to be signed by a local councilor for them to be valid. The local councilor demanded a bribe of 5,000 shillings for each child (more a month’s salary for an employed Kenyan – an impossible amount for Margaret who is without work), something he knew Margaret could not pay. Hence her son’s temporary work as a driver, despite his university education.

I asked Susan and Margaret what actions they would like to see take place against the perpetrators. Susan: I am willing to forgive because if I seek revenge it will be an endless cycle of violence. I asked how the violence could have been avoided. Margaret: Local leaders could be less divided – they are the ones who incited the violence so they are the ones with the power. And what is it that you want to be different about your lives? I asked. Both Susan and Margaret replied: a house. We just want a house.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Jul 31st, 2009