A few days ago, Ram and I were walking from his house to the main road. Ram is the head of NEFAD and my partner here. It was just after lunch, and while the temperature was by no means extreme (it was probably in the mid-eighties at most), the humidity and lack of a breeze meant that after only a few moments outside, one is inevitably drenched in sweat.

Fresh off of a long conversation over lunch, we walked in silence for the most part. I was still familiarizing myself with his neighborhood. Schools, shops, and homes crowd the small, winding road between the main drag and Ram’s house.

Ram’s neighborhood was spared the worst of the earthquake – most of the homes are solidly built and newer construction. No matter what the neighborhood, however, the most ubiquitous sign of the earthquake is found in the crumbling brick walls that generally separate compounds from the road and each other.

These walls are usually made from brick and mud and overnight a significant portion of them crumbled. fell. Throughout my own neighborhood and Ram’s one could see new walls being built – sometimes of concrete and sometimes crafted from the rubble that remained. (I have been told that new regulations require all newly constructed walls be under 4 feet high. I’m skeptical, because I would imagine that regulation is in meters and 1.2192 meters seems arbitrary.)

In any case, Ram and I passed plenty of walls like that. But one in particular stood out because, instead of any attempt to rebuild, two gargantuan spools of razor wire were simply piled onto the rubble.

When Ram caught me looking at it, he told me that it was military barracks. He told me that the Nepalese government had detained many people there during the civil war, and that between September and December of 2003, 49 people were detained there who never made it out. There is no record of their execution or transfer – they simply vanished.

It was a stark reminder of how there is no separation here between these disappearances and everyday life for the families – it is not some theoretical or abstract concept. Ram walks by this military barracks every day. He is immersed in it.

For half a second, I thought to snap a picture of the spools of razor wire, but two things stopped me: the first was the lighting – it was midday and the lighting was horrible. The second was the young man in the guard tower wielding an L1A1 that reminded me that it was a military barracks and it’s generally a poor decision to photograph those.

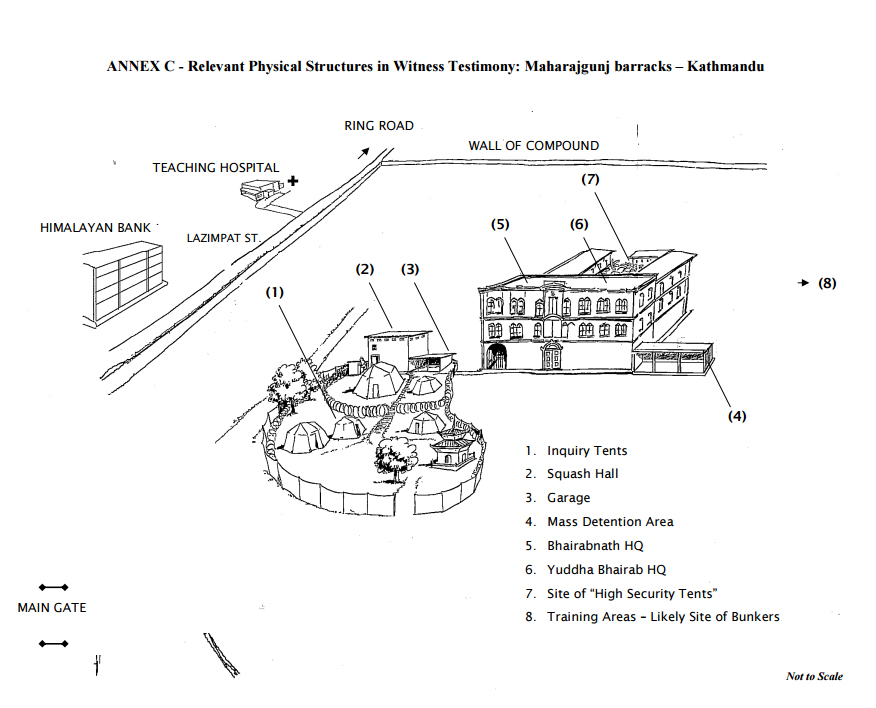

So I hope you accept my apology for not appending a photograph. Here’s an illustration from the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Nepal’s report entitled “Report of investigation into arbitrary detention, torture and disappearances at Maharajgunj RNA barracks, Kathmandu, in 2003–2004:”

And feel free to take a look at the reports by the OHCHR and Human Rights Watch here and here, respectively.

Those aren’t exactly summer reading. They are incredibly depressing, actually. Now, imagine having to think about those two documents every evening on your way home. That is the nature of impunity.

Posted By Dustin Pledger

Posted Jun 29th, 2015

3 Comments

iain

June 29, 2015

Interesting blog! Also raises a question abut the thinking of the military in Nepal. Having yielded peacefully to democracy in 2006, are they adamantly opposed to transitional justice? One would hope not. It would be fascinating to get the perspective of the soldiers and even some profiles. Also, does NEFAD/Ram work for families of the military who lost family members to the Maoist rebellion? Any reason not to? Welcome your thoughts!