The Uganda COVID Quilt

Background

In late 2021 a group of ten women met in northern Uganda to describe the impact of COVID-19 on their families and communities through embroidery.

In late 2021 a group of ten women met in northern Uganda to describe the impact of COVID-19 on their families and communities through embroidery.

The pandemic was raging at the time in Uganda. While the level of death fell far short of that in northern countries, several staff members at our partner organization, the Gulu Disabled Persons Union (GDPU), which operates in Gulu district, had been seriously ill. The pandemic had also claimed the life of Dolly Oryem, a beloved primary school teacher who had worked with GDPU.

The biggest fear was the shortage of vaccines. As Anna Braverman, our 2021 Peace Fellow at GDPU, had written, this was forcing Ugandans to experiment with dangerous local concoctions. Schools had remained closed since the start of the pandemic in March 2020.

The ten women who met to tell their COVID story had all been kidnapped when they were girls by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel group that terrorized Gulu district between 1994 and 2002. The girls were forced into sexual slavery. Many of them bore children to LRA soldiers before they were able to slip away and return to their villages. Often, they were met with suspicion and viewed as collaborators.

As the women struggled to find their footing, they gravitated to other survivors who had suffered the same dreadful experience and formed an association, Women in Action for Women (WAW), under the leadership of Victoria Nyanjura. Victoria contacted AP in the summer of 2021 and requested embroidery training. This produced a series of astonishing but harrowing images which were assembled into the Ugandan War Survivors Quilt. Peace Fellow Anna Braverman wrote powerful profiles of the artists for our website.

Like many before them, the artists enjoyed stitching in the company of other women who had been through a similar experience while at the same time learning a new skill. After completing their war stories they quickly embarked on a new stitching project to describe Africa breads.

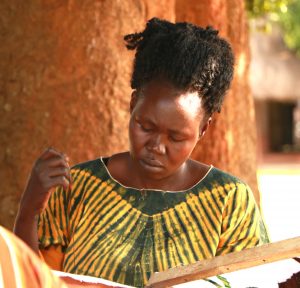

They were also quick to respond to our call for embroidered stories about the pandemic. AP covered the cost of material and outdoor trainings, and this offered the artists a welcome respite from lock-down (photos). Their stories are found on this page and they show – like other COVID-19 quilts – how the pandemic has hurt communities and groups that were already outside the mainstream of society.

They were also quick to respond to our call for embroidered stories about the pandemic. AP covered the cost of material and outdoor trainings, and this offered the artists a welcome respite from lock-down (photos). Their stories are found on this page and they show – like other COVID-19 quilts – how the pandemic has hurt communities and groups that were already outside the mainstream of society.

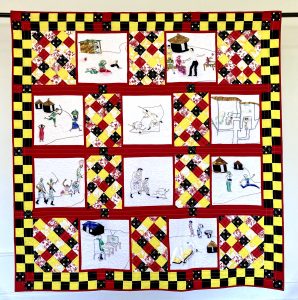

Joan Taylor, a well-known quilter in Ohio, assembled the ten stories into the fine quilt shown on the next tab. She placed the blocks on a background of red, yellow and black – the colors of Uganda.

As of writing, AP has received almost 200 COVID stories from six countries – Bangladesh, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Kenya, and the US. These are being profiled in a catalogue for publication in the spring of 2023. The quilts will then be exhibited widely.

Back in Uganda, WAW members continue to seek out new stitching opportunities. In the summer of 2022, they received training from Bobbi Fitzsimmons, AP’s Quilt Coordinator, and made embroidery for Southern Stitchers, our new online embroidery store. At time of writing, two of the ten artists have sold blocks. (December 2022)

The Uganda COVID Quilt

Artists and Squares

Christine Akuma

Christine and her family rented a house during COVID-19, but had no money and Christine fell behind on the rent. Her story shows her landlord chasing her family out of the house. She and her son are sitting outside after being evicted with her belongings on the ground next to her. Christine was keen to embroider this story because unfortunately, it is not unique in Uganda and she wanted to share the hardships with others.

Christine and her family rented a house during COVID-19, but had no money and Christine fell behind on the rent. Her story shows her landlord chasing her family out of the house. She and her son are sitting outside after being evicted with her belongings on the ground next to her. Christine was keen to embroider this story because unfortunately, it is not unique in Uganda and she wanted to share the hardships with others.

Irene Lumunu

Irene saw first-hand how skeptical people were towards the COVID-19 vaccination. People were very reluctant to get the vaccination even after volunteers held sensitization campaigns. Irene wanted to tell this story in the hope that it would encourage more people to get the vaccine and show that there is nothing to be afraid of. Irene’s story shows a doctor trying to convince patients to get vaccinated.

Irene saw first-hand how skeptical people were towards the COVID-19 vaccination. People were very reluctant to get the vaccination even after volunteers held sensitization campaigns. Irene wanted to tell this story in the hope that it would encourage more people to get the vaccine and show that there is nothing to be afraid of. Irene’s story shows a doctor trying to convince patients to get vaccinated.

Concy Lalam

Concy was devastated when her beloved Auntie passed away from COVID-19. She had been Concy’s biggest supporter and confidant and when Concy received the call, she was not even aware that her Auntie had even tested positive. Concy described her reaction: “It was very painful. I did not hear that she was sick, only that she was dead. I never got to see her or talk to her.” Concy used her block – the stitching and the story – to help her as a way to process her Aunt’s death. It shows a family grieving as a loved on is buried.

Concy was devastated when her beloved Auntie passed away from COVID-19. She had been Concy’s biggest supporter and confidant and when Concy received the call, she was not even aware that her Auntie had even tested positive. Concy described her reaction: “It was very painful. I did not hear that she was sick, only that she was dead. I never got to see her or talk to her.” Concy used her block – the stitching and the story – to help her as a way to process her Aunt’s death. It shows a family grieving as a loved on is buried.

Nancy Layet

Nancy’s square tells the story of domestic violence, which spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic. Men would neglect women and children, and only return when they were drunk. Nancy said that making this square was painful, because it reminded her of all that women had suffered during the pandemic. Her design shows a pregnant woman standing helpless as her partner runs away.

Nancy’s square tells the story of domestic violence, which spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic. Men would neglect women and children, and only return when they were drunk. Nancy said that making this square was painful, because it reminded her of all that women had suffered during the pandemic. Her design shows a pregnant woman standing helpless as her partner runs away.

Nighty Achieng

During COVID-19, Nighty sold produce on the streets to support her family. This became dangerous after the authorities implemented a strict lock down. The police would harass any groups larger than five people and Nighty frequently saw people being arrested and beaten. Her square shows vendors being violently hustled out of the markets by police.

During COVID-19, Nighty sold produce on the streets to support her family. This became dangerous after the authorities implemented a strict lock down. The police would harass any groups larger than five people and Nighty frequently saw people being arrested and beaten. Her square shows vendors being violently hustled out of the markets by police.

Margaret Okello

The police in Gulu District enforced a strick lopck-down to control the spread of COVID-19 and arrested any group of five or more people. Margaret’s square shows a woman who has tried to go to the market with her baby being harassed by the police. She tries to flee while a bystander watches helplessly. Margaret was feeling particularly depressed and hopeless at the time that she worked on this square.

The police in Gulu District enforced a strick lopck-down to control the spread of COVID-19 and arrested any group of five or more people. Margaret’s square shows a woman who has tried to go to the market with her baby being harassed by the police. She tries to flee while a bystander watches helplessly. Margaret was feeling particularly depressed and hopeless at the time that she worked on this square.

Mary Atim

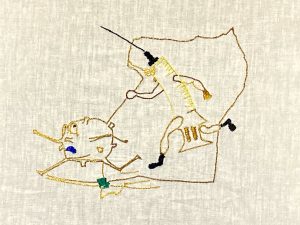

Mary was feeling frustrated with the government’s inaction when she made this lively image. COVID-19 was spreading rapidly through Uganda and she felt that the government was doing very little. Mary wanted to show that COVID-19 can be chased out of Uganda and hopes that her design will inspire people to get vaccinated. It shows the needle in hot pursuit of the COVID virus.

Mary was feeling frustrated with the government’s inaction when she made this lively image. COVID-19 was spreading rapidly through Uganda and she felt that the government was doing very little. Mary wanted to show that COVID-19 can be chased out of Uganda and hopes that her design will inspire people to get vaccinated. It shows the needle in hot pursuit of the COVID virus.

Judith Along

Judith was really unhappy when she made this block. During the height of the pandemic, schools in Uganda were closed and all teaching was conducted at home via television or the radio. Like many other parents, Judith also struggled to make ends meet. There were no jobs, and no money available. Judith could not afford electricity at that time. She is angry that her children and so many others had to suffer. Her embroidery shows a lucky student who has access and can continue to take classes. But even with this access, the quality of education declined due to online learning.

Judith was really unhappy when she made this block. During the height of the pandemic, schools in Uganda were closed and all teaching was conducted at home via television or the radio. Like many other parents, Judith also struggled to make ends meet. There were no jobs, and no money available. Judith could not afford electricity at that time. She is angry that her children and so many others had to suffer. Her embroidery shows a lucky student who has access and can continue to take classes. But even with this access, the quality of education declined due to online learning.

Concy Ajok

Before COVID-19 Concy Ajok ran a successful restaurant, but business slumped when the lock-down was imposed. On some days Concy was only able to serve one or two customers. Concy fought to keep her restaurant open as long as she could but eventually she had to close the doors for good. Concy found embroidery to be therapeutic during this time of isolation and wanted to share her story with others. Her square shows the all-too familiar scene of an empty restaurant while the owner looks on with utter despair.

Before COVID-19 Concy Ajok ran a successful restaurant, but business slumped when the lock-down was imposed. On some days Concy was only able to serve one or two customers. Concy fought to keep her restaurant open as long as she could but eventually she had to close the doors for good. Concy found embroidery to be therapeutic during this time of isolation and wanted to share her story with others. Her square shows the all-too familiar scene of an empty restaurant while the owner looks on with utter despair.

Stella Grace Awok

When Stella’s grandmother came down COVID-19 and was taken to the hospital, Stella looked after her in hospital. Luckily, her grandmother made a full recovery but Stella still remembers how scary that experience was. Stella’s block shows a nurse administering a vaccination. Stella decided on this design because people were resisting the vaccination even even though the vaccine was available. She wanted to show that the vaccine is nothing to be feared. Her design shows the virus in full flight.

When Stella’s grandmother came down COVID-19 and was taken to the hospital, Stella looked after her in hospital. Luckily, her grandmother made a full recovery but Stella still remembers how scary that experience was. Stella’s block shows a nurse administering a vaccination. Stella decided on this design because people were resisting the vaccination even even though the vaccine was available. She wanted to show that the vaccine is nothing to be feared. Her design shows the virus in full flight.