After meeting Sarita, Sabrita, and Fudiya, and hearing about Bipin and Dil, you may be wondering what can be done for the families of the disappeared. The fate of the families and their ability to receive answers about their loved ones is dependent upon a successful transitional justice process.

Transitional Justice (TJ) consists of a series of mechanisms implemented in countries after violent conflicts. It is a relatively new process that responds systematically to mass atrocities and war crimes to help communities and societies both acknowledge the past and move into the future. One of the primary goals of transitional justice is to keep a conflict from repeating itself. If the conditions that led to a conflict are not addressed and altered, it is more likely that the conflict will reignite.

For more information, the International Center for Transitional Justice has a great brief here: What is Transitional Justice?

Part of my work here this summer has been to get acquainted with the TJ process in Nepal and to write a report on the current status of the process as it relates to affected families. The current TJ process has been boycotted by many international organizations due to an amnesty clause included in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act of 2014. This clause, granting amnesty to those found guilty of war crimes, would completely undermine the process and perpetuate a culture of impunity. A Supreme Court case has since overturned the clause, but Nepal’s TJ process remains at risk of failing to complete its mandated responsibilities to victims.

Kirstin and Vicky interview Shree Krishna Subedi, one of the five members of Nepal’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Mechanisms for transitional justice vary based on the context in which a conflict occurred. I have spent much of the last few weeks interviewing family members of the disappeared and leaders in charge of implementing the TJ process in Nepal.

The most critical mechanisms being demanded by the 1,475 families of the disappeared are four-fold:

1. Truth: Families want an answer to two basic questions:

(1) What happened to my family member?

(2) Who is responsible?

2. Exhumations: Families wish for the exhumation process to begin so that evidence can be catalogued to answer the above questions. More importantly they wish to hold funerals to honor the lives of their loved ones, and must wait for the bodies to be returned.

3. Criminal Prosecutions: Once DNA evidence is catalogued and triangulated with witnessed reports, the process of criminal prosecutions can proceed. Nepal’s criminal justice process has been incredibly delayed. Nepal’s peace agreement called for the creation of two councils to lead the TJ process: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons (CIEDP) which have been roundly criticized by observers for delays in implementing their mandates. They have been functioning for three years and are only now beginning their investigations. Ram Bandhari, NEFAD’s founder, contends that this is because the commissions are serving political interests rather than the interests of the families. The delays have protected perpetrators.

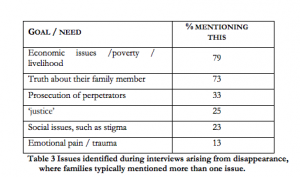

4. Reparations: Perhaps the most misunderstood of transitional justice mechanisms, reparations have been requested to aid families who lost their family’s breadwinner. A disproportionate number of conflict survivors are women who have difficulty joining the job market due to gender discrimination and who have fallen into a cycle of poverty. Following the conflict, the primary request of survivors of the conflict is assistance related to economic issues and poverty. Reparations are not merely monetary payments. They can consist of sustainable livelihoods programming, educational pathways for victims’ children, and other similar assistance programs as well as memorials to assure remembrance in regions most affected.

Simon Robins and Ram Bhandari report on the needs of families of the disappeared

While this post has been a bit technical, I assure you that the ‘mechanisms’ of transitional justice have profoundly human consequences. In a country whose civil war was fueled largely by economic feudalism and gender inequity in rural regions, it is incumbent upon the government to address the root causes of the violence. The reasons for committing to the transitional justice are not only moral (although they are that) but also a national security imperative to prevent the recurrence of conflict.

My interviews over the last few weeks in Bardiya and Kathmandu have highlighted the vast gulf between the high-level political mechanisms and the day to day lived experiences of conflict survivors. Bridges of communication must be built to cross this chasm, or the process runs the risk of failure.

Posted By Kirstin Yanisch (Nepal)

Posted Aug 20th, 2017