The Nepal Tiger Quilts and Bags

Background

Kancham, left, and Pooja made blocks for the Tiger Quilts. Kancham holds one of the first Tiger bags.

The three quilts featured in this pages honor tigers in Nepal. They are the product of a partnership between AP and a group of women who lost close relatives to the disappearances during the conflict in Nepal (1996-2006). Our friendship with these women is deep. It has forced us to think outside the narrow confines of a normal partnership and seek innovative approaches. For this we are grateful.

As we have explained elsewhere in this site, most of those who disappeared during rhe conflict in Nepal were seized by members of the security forces. A smaller number were kidnapped by Maoist rebels.

The district of Bardiya suffered more disappearances (272) than any other district in Nepal during the conflict. This was partly because the Tharu people who live in the region were viewed as sympathetic towards the Maoist rebels. But many of the disappearances were also the result of local jealousies.

AP’s involvement with the Bardiya cooperative began in 2015 and came about as a result of our partnership with NEFAD, the network of family members of the disappeared in Nepal. Most members of the Bardiya cooperative belong to NEFAD and between 2016 and 2018 we sent four Peace Fellows to help the cooperative members to describe their work through embroidery. We raised funds through a series of appeals on GlobalGiving, starting in 2015. The embroidery training was led by Sarita Thapa, the cooperative coordinator and an experienced seamstress.

Like so many others who have contributed to quilts, the artists used their first blocks to commemorate their lost loved ones and describe the circumstances of their capture. These blocks were turned into two striking memorial quilts by the artists themselves, with help from Bobbi Fitzsimmons, an AP Board member and experienced American quilter who visited Bardiya in April 2019. The quilts and the artists are profiled on these pages.

After producing the commemorative blocks, the women decided to use their embroidery skills to honor the tigers that live in the nearby Bardiya National Park. They wanted to produce something that would have wide appeal, and maybe even bring in some money.

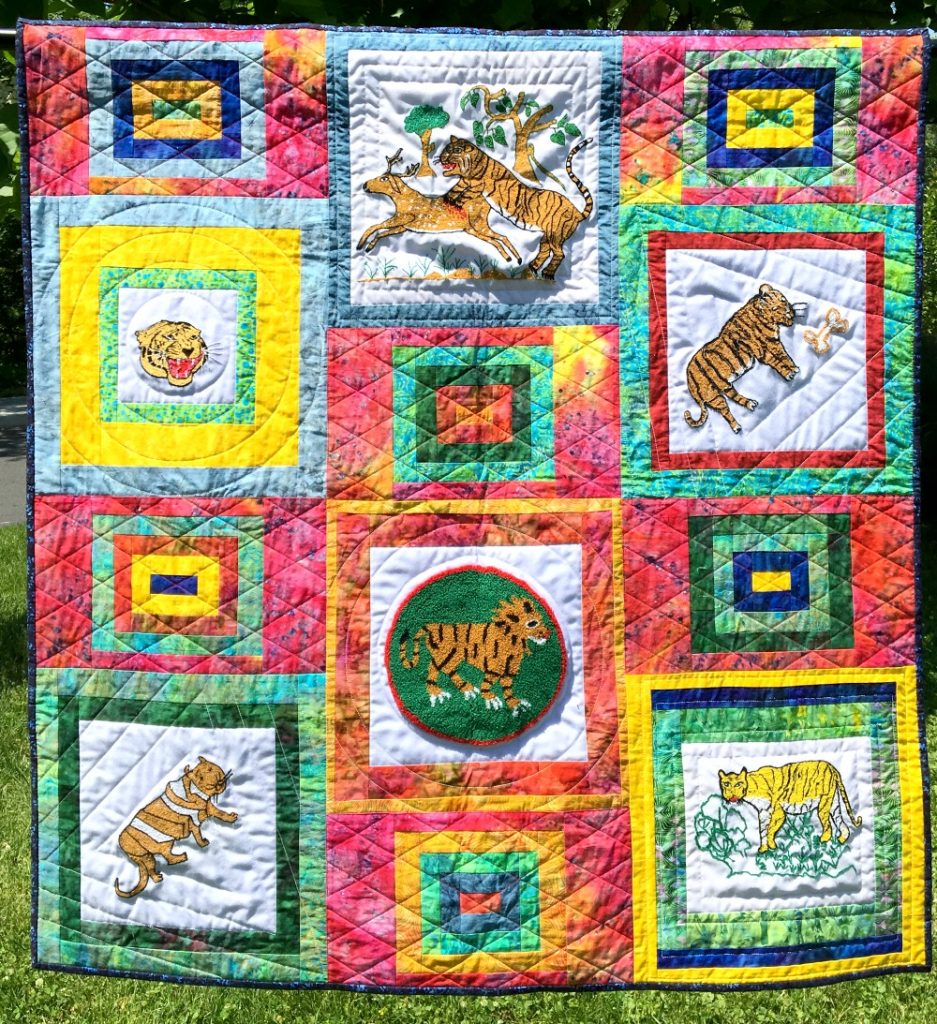

They made over 50 blocks featuring tigers. Half of the blocks were brought back to the US and assembled by Bobbi Fitzsimmons and Connie Moser into the three Tiger quilts shown on these pages.

Bobbi took one of the quilts with her when she visited Bardiya to work with the cooperative in 2019 and it now hangs on the wall of the cooperative’s office. The other two quilts have been shown at exhibitions, most notably at Karlsruhe in Germany in December 2018 (Photo).

This still left left over 25 embroidered Tiger blocks which had not been used in quilts and the cooperative decided to turn them into embroidered bags, in the hope of earning some money and start a micro-business.

This was a new departure for AP as well as for the women. Up to this point we had viewed quilts as a tool for advocacy and story-telling, not income generation. We loved the idea of animal bags and have since suggested it to women in Kenya and Mali. But it immediately raised two important questions: First, could the women produce high quality bags? Second, would we be able to find a market for the bags?

AP and the cooperative members decided that it was worth the risk and invested around $500 in producing sample bags. Peace Fellows Vicky Mogeni and Kirstin Yanisch helped Sarita and her team to produce embroidered tigers in Bardiya and commission tailors in Kathmandu to produce a range of different model bags.

We profile some of the Bardiya artisans and their bags on these pages. There is no mistaking their enjoyment at working together and their pride in what they produced. Indeed, looking at their mostly smiling faces, it is easy to forget the pain they still live through.

But, as expected, it proved difficult to find a local market. Sarita won agreement from John Sparshatt, the owner of Wild Trak, a superb ecolodge on the edge of the Bardiya park, to display some of the bags (photo) to his guests. Kirstin and Vicky brought some bags back to the US and made some sales.

But by the tme Bobbi Fitzsimmons visited Bardiya in April 2019, the cooperative had decided that their first tiger bags, while lively and colorful, would probably not find a market. They took advantage of Bobbi’s visit to come up with new and more modern designs and to rethink the method of production. Their new bags can be seen on these pages. They hope to make and sell 100 Tiger bags in 2020.

The Tiger bags have led to other innovations. When we first began offering embroidery for sale (in Mali), we assumed that the stories of the artists would be the main selling pitch. It is certainly true that the Bardiya bag-makers have a powerful story to tell.

But – at their request – we are also embracing conservation. According to experts, the number of tigers in Nepal has doubled to 235 since 2009 – a rare conservation success story. Living next door to Tigers, and seeing their impact on tourism and the environment, the Bardiya artists want to contribute. In 2021 they will look for partners in Nepal and internationally to promote their unique message of human rights, conservation and women’s empowerment. (October 2020).

Artists and bags

Geeta’s brother, Lallu, was forcibly taken from his home in Sujanpur in March 2001. Her father went to see him in the barrack to sign for his bail. During his hearing, Lallu suddenly disappeared. Lallu was a student and was not a Maoist, but it was the worst time of the insurgency. Geeta mentions how the army often took young men who were considered a threat. Geeta was seven years old. She has four brothers and is extremely gifted in embroidery; she learned to sew very fast. Geeta received compensation for her loss and purchased some land with the money. Upon reflecting on the memory of herbrother, Geeta states: “He was very good and well educated. He was always trying to educate me.” Geeta produced blocks for both memorial quilts.

Sarita is the inspiration behind the Bardiya cooperative. She was eleven when her father Shayam was denounced by a cousin as a Maoist and detained. Sarita, her mother and younger brother were then ostracized and driven from the village. Sarita gave up school to concentrate on the search for her father which has cost the family an estimated 200,000 rupees ($2,000). She endured further tragedy after her husband died from a snake-bite. But these misfortunes only stiffened Sarita’s resolve. Sarita is a strong believer in embroidery as a means of empowering women and has led the projects to produce 50 memorial squares and Tiger bags.

Sunita mourns the loss of her sister, Kriti, an active Maoist cadre who was killed in a confrontation in 2001. The Maoists buried Kriti in the jungle, and her body was later retrieved – one of only two of the 25 victims who could be reburied by family members. Sunita and her parents plan to use the government compensation to build a house in Kriti’s memory. Says Sunita: “I can’t forget. She was a good person.”

Pooja’s father Hukum had been farming in India when he disappeared in 2001. Soldiers took Hukum to an army base near the family home and national park. He never reappeared, and Pooja – who was a year old at the time – remains protective of his memory. She concedes that her father had once been a Maoist sympathizer but says he was no longer active: “He was living an ordinary life.

Alina was an infant when her father Hira Mani disappeared in 2003. Hira made furniture and earned 90,000 rupees a month – a significant amount. One day, he went to work at a neighbor’s house and never returned home. Soldiers came to the family home and questioned Manju, her mother. Manju was about to follow them when a neighbor stopped her, afraid that they would take Manju away as well.

Belmati is older than most of the other cooperative members and she rarely smiles. Belmati lost a son and two daughters-in-law during the conflict – a devastating loss for one family. When AP first met Belmati in 2016 she had only received 100,000 rupees in compensation. The cooperative brings companionship to Belmati, but it will never make up for the loss of her family members: “I remember them all the time, when I’m working or when I celebrate a festival, or when I see other children. I have kept my son’s clothes…we want compensation and proper answers…we lost everything.”

In the afternoon of 2002, Kancham’s family threw a modest party at their home. The army was out patrolling and heard that Maoists were hiding in the village, so they came and watched. They shot through their family window without warning, killing Kancham’s brother. Later, the army returned and burned down their home. Kancham was nine at the time and was not home when this event took place. Her brother was 26 and married with two kids. After he died, his widow went with another man and took their children. Kancham did not receive compensation for the loss of her brother, as the payment goes to the wife or the kids. Kancham remembers her brother with fondness; she states: “He could support his family well.”

The First Nepal Tiger Quilt

The Second Nepal Tiger Quilt

The Third Nepal Tiger Quilt