In the previous post, I shared a very general introduction to bonded labor. In the late 18th century, Nepal was newly unified as one state, and ruling families were given land grants in the Terai. The land grants entitled these new landowners to collect revenue from those who cultivate the land which is how the Kamaiya system developed. This impacted the indigenous Tharu ethnic community who lived in these regions.

You wouldn’t think that malaria would have much to do with this story of bonded labor, but the eradication of malaria in the western Terai led to the unexpected consequence of furthering land grabbing by new migrants. The Tharu people have greater genetic resistance to malaria which was a great superpower to have if you lived in the lowland plains regions of Nepal.

When the Nepalese government worked to eradicate malaria in the 1950s and 60s, non-Tharu migrants moved in and occupied land Tharu people lived on, but may not have had written records for. Settlers could register the land in their own name and force Tharu families to work the land as agricultural laborers.

Visiting the Tharu Cultural Museum in Dang is an interesting experience knowing this background. The site of the museum used to be a boarding house for freed Kamlaris, a form of bonded labor specific to women and girls. As the girls grew up and moved away, the site was being unused.

The location was a reminder of the legacy of marginalization of an indigenous ethnic community. By turning it into a cultural museum, the site was transformed into a place of cultural pride and memorialization.

The name “museum” may not actually be the most accurate characterization. BASE is leading the conversion of this space into a multipurpose community gathering site, income-generating attraction, and center for cultural preservation. BASE runs livelihood training programs from the location with some of the products produced destined for sale in the museum’s gift shop.

We visited a tailoring training where women practiced creating traditional Tharu dresses for sale at the museum. Visitors also help pay for the latest construction developments through the museum entrance fee, traditional dress rentals, and an on-site restaurant.

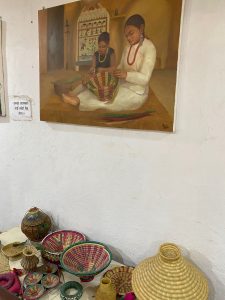

In the museum exhibits, various traditional tools were on display that I recognized from the designs the embroidery training participants chose to depict.

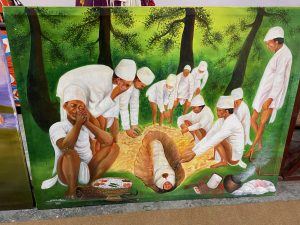

Paintings on the walls showed different life stage events and community events.

It was interesting to learn more about the communal governing system where households vote for the local leader who serves a one year term. These elections always coincide with the Maghi Festival in January or February.

I was encouraged to try on one of the traditional dresses available for rent at the museum and I’m so glad I got to wear not just the dress, but all the embellishments and jewelry that make the whole outfit.

We ordered some traditional items off the menu to try out. Our shared plate included some cooked and spiced snails, breaded and fried river fish, steamed rice flour bread sticks, crunchy fried lentil and rice patties, and some rice beer.

All-in-all, it was a really fun day!

A big takeaway for me on the visit was the exciting potential for multi-use public spaces in community building. A physical location that serves multiple goals seems well positioned to cater to both in-group and out-group guests such as, in the cultural museum’s case, both Tharu and non-Tharu visitors.

This theme would carry over a few days later during a visit to the Disappeared Persons Memorial Park in Bardiya.

Posted By Therese McCarry

Posted Jul 20th, 2022

1 Comment

Minar

January 28, 2023

Thanks for sharing the ritual culture, that few people talk about it.

have nice day.