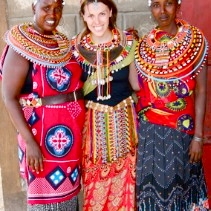

The Magic Five – the women who composed my timed and measured team of jewelry makers – deserve introductions. After only a few days, they became my sisters.

Photo: Kate Cummings, Umoja Uaso. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009. Kenya

Photo: Kate Cummings, Umoja Uaso. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009. Kenya

Naibala (“Nye-ball-ah”) is one of the elders in the community. Her name actually means “brown”, a nickname from the women because of her lighter skin (Rebecca, what is her real name? Rebecca yells to Naibala – what is your name? Naibala is too far, and Rebecca laughs, turning back to me: I don’t know). She is a storyteller, a mother of mothers, and has the loudest laugh (warm, just often enough). She is best at creating the multi-layered orange and yellow necklace, strung with wire.

Photo: Kate Cummings, Umoja Uaso. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009. Kenya

Dtipayon (“Dip-ay-own”) is an elder, too, but quieter. She is so beautiful in person, it is quieting just to see her. She works with hardly any breaks, only stopping occasionally for a pinch of chew (tobacco). She smiles during Naibala’s stories, and can sit in one position for so long without any signs of restlessness. Her piece of jewelry is a beaded bracelet, carefully strung through a piece of recycled car tire.

Photo: Kate Cummings, Umoja Uaso. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009. Kenya

Photo: Kate Cummings, Umoja Uaso. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009. Kenya

Anna is one of the youngest woman at Umoja, maybe no older than 22. She is giggly, and keeps a close eye on me. I held impromptu yoga sessions during our long days of immobility, and Anna was the most enthusiastic – and amused – participant. When she laughs (again, this is often), her cheeks rise so high they threaten to obscure her eyes. She has a little girl, named Becky, who loves to wear the women’s jewelry and imitate their undulating dance. Anna specializes in making a modern version of the Samburu headdress.

Photo: Kate Cummings, Umoja Uaso. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009. Kenya

Sericho (“Sayeree-cho”) is young, maybe 25. She has two children, the youngest of whom comes tottering for her from their hut each hour, indifferent to systems or time constraints. Timoke, the youngest, pulls on her beads, drags her dress in the dirt, and she – in one graceful motion – sweeps the child under her dress and nurses him, and he is immediately asleep. Sericho breaks into song, sometimes dancing in place; the others treat this as normal. She is making a modern necklace with many beaded strands, each with multi-colored extensions.

Sentiyo (“Sen-tay-oh”) is probably the same age as Sericho, but is not as gregarious. She has the ever-pouting child, Brett, who is no more than 2 and is also impatient for his mother at all times (tugging, pulling, crying). She employs the same technique as Sericho in quieting her baby (she has an older girl, also). She likes to joke with Sericho, and laughs more than she talks, which gently nods the plastic rose in her headdress. She specializes in a traditional necklace, with rounds of colorful beads and dangling seashells.

Each day, we gathered around 8:30 in the morning on the cowskin under the acacia. The women would bring their unfinished pieces with them, untouched since the day before when we stopped the clock. I laid out the scales (brought from the US) and, while the women beaded steadily, I asked Rebecca about the prices for each material that was being used. And, somewhere in the morning hours and the longer afternoons, we came up with some numbers. They are rounded, not sharp: in the systemless situation, guesses become facts and estimations turn into solid foundations for further calculations. These five pieces were among 35 pieces Rebecca is taking to the US, and each one needs to be priced (based on the estimations from the 5 that were thoroughly measured), so the estimations were extensive.

The enforced timing was almost unnecessary. The women worked with only about 10 or 15 minutes rest from 8:30 to 5 (we took lunch, don’t worry). They set the pace, and somehow there was relaxation throughout – songs, stories that entertained me despite my limited Samburu, and the ever-present children. In the end, the five pieces took anywhere from 9 to 19 hours to make; these pieces are selling for low prices that cannot cover these hours. I was advised by a specialist in African handicrafts to set the hourly wage at 31 Kenyan shillings: this is about 40 cents. And, I am told, this is fair. What’s more, this is higher than what they were charging in their market. The price I was calculating also included the materials, overhead, and a profit margin, so there is more to this number than the hourly wage.

Still, sitting with these women all day, I wanted more for them. And maybe more is possible with this beginning. With my (lack of) faith in systems, I need encouragement to believe. But this structured approach to making and selling their jewelry abroad might just help Umoja be the self-sufficient community it dreams to be. And, I needn’t remind you, this is up to Us as much as Umoja. It’s up to us to find out how to borrow from the right moneylenders to start up businesses in the area. Not because We may have money to buy jewelry: this is too simple. Up to Us because we all have control over how we interact with the extensive network of people present in each of our daily lives – in our coffee, our eggs, our cars. Behind each of these commodities or resources on which We depend are people; as personable and individual as Sericho, Naibala, and Rebecca. We cannot be reminded enough that the distance separating us is small; the realities connecting us are larger and, from this cowskin rug seat under the acacia, much more important.

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Jul 2nd, 2009