In between a trip to the Yuyanapaq exhibit at the Museo de La Nacion and a viewing of the documentary Lucanamarca, this past week was marked by the arrival of three American filmmakers from D.C. They are here to begin the process of what will eventually become the making of a documentary film on EPAF’s work (you can check out their production company here). The most fascinating part of their visit so far for me is that it has really illuminated the challenges that EPAF is facing working in Peru at the moment. Why? Well, the filmmakers had planned their visit with the hope of filming an exhumation being carried out by the EPAF team. However, the day before they arrived, something came up and the public prosecutor decided to cancel the exhumation. Thus, the filmmakers were left without an exhumation to film and so quickly had to come up with an alternative plan.

This setback is illustrative of a greater trend of obstacles that EPAF has faced over the last year, and something I’ve become more and more aware of during my time here. Exhumations, and the complex and extensive process of interviewing family members, examining the remains, and holding clothing exhibitions are highly dependent on the Peru’s judicial system. Now, I know that last week I wrote about the importance of the victim’s achieving retributive justice and I still believe that this is of the utmost importance for true reconciliation to occur in the country. However, through my experience at EPAF, I’ve come to determine that transitional justice in Peru, when it comes to recovery of the disappeared, is much too grounded in retributive processes. This does not mean that restorative justice has been completely ignored. Indeed, the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission was lauded for their comprehensive report (which will celebrate its six-year anniversary in August) and some of their recommendations have been acted upon by the state.

Nor does it mean that cases of forced disappearances are being prosecuted in the courts here. What it does mean is that almost every detail of the exhumation process is dependent on the legal apparatus. In order to even reach the exhumation stage, a case must be filed with the public prosecutor in the appropriate region (usually where the family of the disappeared are living, or where they suspect the body to be buried). From this point on, the prosecutor must be involved at every step of the process-which includes being present at the exhumation itself. This requires a substantial amount of time on the part of the prosecutor. In addition, cases of forced disappearance frequently don’t have a clear defendant. Many of the forced disappearances were likely carried out by the military and today, the state claims that all records of who was stationed at what based during the time of the violence have been burned. In the end, these two factors often result in these types of cases not being treated as a priority by the judicial system, and there is no real alternative for but to go through that system.

This dynamic poses an obstacle to EPAF, as they are constantly forced to cancel, reschedule, and often only participate peripherally in exhumations. It inconvenienced the filmmakers who had arrived hoping to see EPAF in action. But the people it hurts the most are those whose voices tend not to be heard: the families of the missing. When the cases they file are not prioritized, it means an even longer wait for the recovery of their missing loved ones. Often, family members know exactly where the grave is located, yet cannot access the remains without the oversight of the judiciary. Part of my work this summer is trying to examine how this process could be reformed so as to work principally in favor of restorative justice for the victims, without precluding retributive justice in the future.

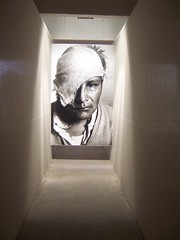

But getting back to the filmmakers. They ended up taking a trip to Ayacucho this weekend that I think will prove to be just as interesting as an exhumation. Zack went with them, so I’ll let you read more about it in his blog. In the meantime, below are some stunning photos from the Yuyanapaq exhibit I mentioned earlier.

Posted By Jessica Varat

Posted Jul 26th, 2009