Some conflicts are either too political or too complicated for outsiders (and maybe even insiders) to understand, and yet one is nevertheless expected to take a side. Although I studied Middle Eastern history in college, knowing that the Lebanese Civil War was so complex, and that I would never fully understand it, I chose to remain blissfully ignorant, essentially ignoring it in my studies. However, when I found out that I had been accepted to an internship position at a peacebuilding NGO in Lebanon for the summer, I realized I needed a crash course on the subject to, at a minimum, recognize some of the names of certain key figures, and have a rough idea of what had happened (for a general overview, I would recommend Al Jazeera’s 15-part series on the War in Lebanon from 2001).

One of the most well-known symbols of Beirut: Mohammad Al-Amin Mosque and St. Georges Maronite Church standing side by side in Downtown Beirut

Surfing through Wikipedia, it’s easy to fall down the rabbit hole, reading about one massacre, carried out in retaliation for another, which was reprisal for an assassination, which was spurred on by other killings, and so on, and so on; a vicious cycle of violence begetting more violence which engulfed the country for fifteen years.

Hindsight, they say, is 20/20; and as a foreigner scrolling through Wikipedia, this was plain enough for me to see, but for someone who had been affected by the conflict or been at the heart of the violence, it must have been blinding, a state that contributed to the perpetuation of these injustices.

While watching video clips and documentaries on YouTube, someone I noticed who seemed also to recognize the danger of this cycle was a former combatant named Assaad Chaftari. He was featured in two videos: an Al Jazeera report on the over 17,000 individuals still considered ‘missing’ from the civil war and a France 24 report on the legacy of the civil war.

At the time I did not expect that I’d have the opportunity to meet Assaad in person, but when talking with JP about potential topics for blogs, he suggested a list of organizations and individuals whose work I could highlight, and given that he and Peace Labs had collaborated with Assaad and Fighters for Peace, he contacted Assaad and asked if he would be interested in meeting with me. The following stems from our July 31, 2017, meeting and includes context derived from a range of external sources.

Assaad studied engineering before the war, but eventually became a high-ranking intelligence officer in a Christian militia during the war – a status which put him in the position to be responsible for many deaths throughout the conflict. However, he’s now vice-president of the organization Fighters for Peace, and is still involved in Initiatives of Change (IofC), the organization he credits for having transformed him.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Buchman

Frank Buchman, founder of IofC

IofC started with the work of the American minister Frank Buchman, who in the 1920s was instrumental in the development of the Oxford Group, an organization that sought to address societal problems through personal transformation. In the 1930s, during the build-up to WWII, the organization took on a new name derived from the argument that, rather than rearm militarily, European nations should rearm morally. The name Moral Re-Armament is still used in Lebanon, but the organization was officially renamed Initiatives of Change (IofC) in 2001.

http://www.iofc.org

Fighters for Peace is a much newer organization: a Lebanese NGO comprising former fighters from the Lebanese Civil War who came together in 2012 in response to the violence in Tripoli, with a desire to prevent a new generation from repeating the mistakes of the past. The two main goals of the organization are: 1) creating awareness about – and immunizing youth against – violence and radicalization; and 2) changing the hearts of ex-fighters.

http://fightersforpeace.org

According to Assaad, former fighters may be in a variety of situations regarding their past. Some may praise the war and the wartime as a period when life was easier and when they were appreciated or even celebrated as heroes. Others may be totally silent, never speaking of it, assuming their children and grandchildren don’t know that they were a part of the war. Some may even regret their actions, but keep it to themselves for a variety of reasons.

This situation is detrimental, however, particularly for the youth who subconsciously inherit certain ideologies or mindsets from school, their parents, their society/community, politics, and the media. For this reason, Assaad says he could not continue hiding, as many still do, saying that he wasn’t wrong, that this was the logic of the war, that he was defending himself/his cause, or that he was only following the orders of his many superiors.

In 2000 Assaad published an open letter in the Lebanese press both apologizing for his actions during the war and stating his forgiveness of those who acted against him and his family or community. “At the end, it was clear that I had to take this commitment for the sake of redeeming, maybe, what I had done and for the sake of the generations that would follow. Because I was somewhere a victim of the silence of the generations who came before me, and I did not want my son and the youth to be my victims again. Sometimes staying silent is a worse sin than what you did.”

Assaad began this transformative journey towards the end of the civil war, during a period he recalls as the darkest of his life. At that point, he and his wife were forced to leave Christian areas and live among their former enemies, leaving everything they had for their former friends and allies to appropriate. It was then that they encountered Initiatives of Change – a group he describes as saying: “We are against you in politics, but we are with you on a human level, and we want to seek what is good for you on a human level.” Assaad’s wife was the first to go, and eventually she convinced him to join her despite his initial suspicion and doubts as to potential hidden agendas, leadership, funding, and foreign influence. Eventually, though, he started to regularly attend their meetings and participate in their dialogues where he interacted with different groups, among which were the people he had once hated as enemies.

It was then that Assaad decided to change. “It does not begin by itself,” he says, “you have to open the door.” And he notes that “change is a process, a long process, a very painful process. Especially when there is blood on your past. Some things you can change easily, if you go and express your regret, redeem and/or repair, but you cannot bring back to life someone you’ve killed.”

For someone as zealously devoted to his cause as Assaad was, “admitting that you were wrong is the toughest part of it, maybe. Admitting it to yourself is as difficult as admitting it to others.” And doing it publicly is toughest of all.

Undaunted, after his transformation, Assaad started working to change others – to join a call for people to recover their moral compass, and to return to moral values and a non-violent ethics. A major component of this transformation has been his approach toward violence and war itself. He hopes that his apology and the apologies of others from different sides – different militias and/or religious/ideological causes – will help demonstrate to others that the use of violence in general is wrong, regardless of the cause.

Nonetheless, apologies, and even accountability, for a fifteen-year civil war, in which almost everyone, especially at the higher political levels, was implicated, are few and far between. As Assaad discussed this with me, he described the public apologies of which he was aware. Of these, Samir Geagea’s was perhaps the one that received the most attention. Geagea had been the leader of the Lebanese Forces party during the war, and later imprisoned (many say for exclusively political reasons) for eleven years in solitary confinement from 1994 until he was released after the Cedar Revolution and the Syrian withdrawal from Lebanon in 2005. In 2008 he presented an apology; however, the old political divisions remained, with those already in favor of Geagea supporting him, and those already against him seeing it as politically motivated: “An apology coming from the brain, not the heart.”

http://www.lebaneseexaminer.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/samir-geagea-1024×682.jpg

Samir Geagea

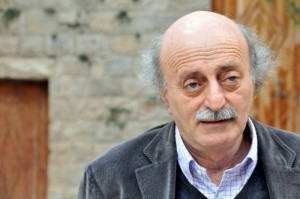

According to Assaad, Walid Jumblatt, leader of the Druze community in Lebanon, and son of Kamal Jumblatt, the assassinated founder of the Progressive Socialist Party, also expressed regret on two occasions, but “in the Lebanese way, where you speak of everything but you don’t speak of what is needed, but you express it one way or another.”

http://www.michaeltotten.com/archives/2009/09/the-warlord-in.php

Walid Jumblatt

The third Lebanese group Assaad mentioned was the Organisation de l’action communiste au Liban (OACL), which, he said, carried out a critical study of their behavior during the war, but did not publish it, keeping it internal to the organization. Assaad also noted that only one publicly expressed sentence of the former leader expressed regret.

The group Assaad felt was most serious in terms of its apology was the Palestinians. In 2007, their embassy in Lebanon issued a declaration apologizing for their actions during the war, noting especially that they should have acted differently toward a hosting country such as Lebanon. However, due to internal Palestinian political divisions, some factions supported the apology, while others were against it. According to Assaad, this is one of the reasons why the declaration did not receive the attention it deserved. Nevertheless, Assaad answered them. He organized the signatures of 44 Christian figures, and two months later published a statement accepting their apology and apologizing in turn. For Assaad, personally, it was also an occasion to reconcile with some of the leaders of the Palestinians in Lebanon.

One reason Assaad felt apologies are hard to come by is that those same names I found time and again on Wikipedia and in accounts of the Lebanese civil war are the same names that I hear today running the government. As he said, “in general, after civil wars, the entities which took part in the fighting are dismantled, while in Lebanon, they are in power again – they are in power now. Not only that. They kept their names, I’m speaking of the political entities or militias, and their military names.”

In an attempt to end the war, a general amnesty was granted, meaning that, as Judy Barsalou says, “only one major war criminal, Samir Geaga, was tried and imprisoned after the civil war ended in 1990. Because former warlords held key governmental positions, no effort was made at a national level to account for the grueling fifteen-year civil war” (Judy Barsalou in Barry Hart, ed. Peacebuilding in Traumatized Societies,p. 36).

Monument to the civil war martyrs of the Christian Kataeb party

Assaad added that “the communities are [still] behind those parties and those names,” and that the popular sentiment is that if you come forward and apologize, “you are weakening your group, even if you have already left them. Because it means that you are a traitor to your own. And I was – I’m still – called by some of my comrades as a traitor. Because they felt that accusing myself – and I never accused others of my party or my group, never – accusing myself was enough for them, and that it meant that I was accusing everybody.”

He also noted that there may be a cultural element to it as well: “You show weakness when you forgive, or when you ask for forgiveness.” Furthermore, “in Lebanon, when you want to forgive someone, we don’t have the word ‘I forgive you.’ You say, ‘may God forgive you,’ or ‘may God forgive what is already in the past’ but we don’t use the word ‘I forgive.’ And when you ask for forgiveness, you use the plural. We don’t say ‘I am sorry,’ we say ‘forgive us’ – in the plural. So the individual does not exist. ‘سامحونا’ [sam7ouna], we say in Arabic. Meaning, forgive ‘us,’ never forgive ‘me.’”

When I asked about the end of the civil war, Assaad countered with “did it end?” stating that he felt the conflict was still ongoing. He mentioned that the previous week, when speaking at a public event regarding the process of reconciliation, he commented that ‘Lebanon is maybe the only country which has known a civil war and still commemorates the beginning of the civil war, and not its end.’ And the lack of a specific, acute end to the conflict, combined with the continuation of events, as well as the lack of a concerted effort to deal with national/collective or personal trauma and historical issues going back centuries, further contribute to the sense of perpetuation of the war. As Barsalou notes, “instead, national authorities made physical reconstruction the top national priority” (op. cit., p. 36). To this effect, the downtown area, which had been all but destroyed (sometimes intentionally) during the war, was entirely rebuilt and refashioned into the posh, although largely empty, central district it is today, covering over any reminders of the devastation it had endured during the war.

View of the reconstructed central downtown area of Beirut

Much the same has been done in other spheres related to the war. The common excuse is that the war is still too recent, and although officially stopped, the lingering causes and tensions remain latent in society, nothing having been resolved by the fifteen years and an estimated 150,000 – 200,000 deaths. Many say that to start a process of digging up the truth and rehashing the experience of the war would only reignite those suppressed feelings and bring about another civil war.

Memorial to the assassinated Christian militia leader and president-elect, Bachir Gemmeyel (left)

Memorial to the assassinated Sunni Muslim Prime Minister, Rafic Hariri, in front of the Saint Nichan Armenian Orthodox Cathedral (right)

Assaad, however, believes that the country has become stuck at the transitional phase, and that these issues still need to be addressed. And the best way to deal with these issues, he says, is “by addressing them. It’s as simple as that. And writing our history. Writing it even if we don’t agree on it.” He then encouraged critical thinking on the part of the reader to realize that that there are different versions of the same events, but not to pick a version – instead, to recognize that “this is the truth, in the end, the truth of everybody is the real truth.”

Assaad proposed that history be written and told at three levels: the personal, which would involve listening to the people who lived it, who were victims of it, or who lost relatives because of the event; second, the community level; and third, a national level to discover what causes civil war and how to prevent it in the future.

Street art from Beirut’s southern suburbs

He noted that in schools the history textbooks end with the creation of an independent Lebanese state because there’s too much controversy about the history since then. He added that there have been five national commissions tasked with writing an official history book, but that none of them were able to produce a result, particularly because politicians raised issues from centuries ago as new issues.

This means that many people today, particularly the youth, have a limited understanding of the war, still conveyed to them through an ideological or sectarian lens. “If they know,” Assaad says, “they know sometimes the results – what they hear from their parents” about which side killed people from which other side – a conclusion meant to “summarize the whole history of the relations” between the groups, focusing on the negative aspects without addressing the full details and ignoring incidents of people helping each other during the war regardless of ideological or religious differences.

He suggested that students and teachers be taught about the losses incurred during the civil war: “The figures are shocking, sometimes; and this is a good way to tell people that you cannot go to war for free.”

Assaad and Fighters for Peace are particularly involved in working with youth for this reason. He adds that “being young is very dangerous. Because you are enthusiastic, first; you look for adrenaline, second; and third, you can be convinced of a cause very easily. While if you are much older, you are wiser at a certain level, so you think twice before engaging. And you try to see what is behind it and why.” Nevertheless, the approach, strategy, and techniques are largely the same. “In general, there’s not a huge difference in the logic that brings you to carry weapons and to kill.” And for Assaad and Fighters for Peace, their personal history gives them an advantage in this regard because from their experience, they understand the logic of war and of the fighters themselves, and communicate to them in a way they can relate to – without academic or theoretical jargon.

Recently, Fighters for Peace has been involved in the Roadmap to Reconciliation project in Tripoli alongside Peace Labs and several other organizations. Regarding differences between dealing with fighters from the civil war, and those from the recent conflicts in Tripoli, Assaad notes, “first, it’s a Muslim-Muslim conflict in Tripoli. Two, it’s recent. So when you address ex-fighters of the civil war, you address people who are 52 or older. But when you address fighters of the recent incidents in Tripoli, it’s 15and above.” Additionally, “most of the reasons for the fighting in Tripoli were because of poverty, while the Civil War had political and ideological motives behind it. Of course, poverty was one of the reasons too, but it was not the essential thing.” Moreover, “while the Civil War was political at a certain level, and many of the events were commandeered by politicians, in Tripoli it’s more obvious.” Assaad gave the example of battles named by the fighters themselves for the politicians who distributed money and weapons. Of the 21 or 22 rounds, it is known why and who is behind each one. And although to a certain extent it could be compared to the situation in Palestine during the Civil War, an additional component to the recent conflict is the effect of events in Syria.

For all these reasons, Fighters for Peace prepared two camps for ex-fighters: one for those from the Civil War, and one for fighters from the more recent conflicts. Assaad says that they want fighters from Tripoli to address their peers because while no one can doubt his qualification to speak on the subject, he acknowledges that it makes a difference being a Christian from Beirut talking about war and peace.

Overall, Assaad is optimistic for the prospects of continued peace, if only because of an international consensus from the major, and even some regional, players that Lebanon be “kept aside.” At the very least, external forces are not encouraging a new civil war in Lebanon, whether because they need it as a model of conviviality for elsewhere, or as a buffer or release valve to contain some of the pressures of its regional neighborhood. He also pointed out the internal disequilibrium in military force that has thus far prevented any internal opposition, and, given the lack of interest in opening an internal front, looks to be sustainable for the near future. Additionally, Assaad believes there is greater awareness of the costs of war, and he also credits the many NGOs and civil society organizations working against discrimination, and for dialogue, non-violent approaches, conflict resolution, historical memory, and oral history, as contributing to the stability of peace.

In addition to the work he does for his organizations, his other outreach and speaking engagements, and his appearances in documentaries and news segments viewable on TV or YouTube, Assaad has also written a book, La Vérité même si ma voix tremble, which, he says, is not a history of the war, but a personal account of his experience before, during, and after, and why he’s doing what he’s doing now.

To learn more about the work of Fighters for Peace or Initiatives of Change, visit their websites:

Posted By Alberto Gimenez (Lebanon)

Posted Nov 10th, 2017