At first, I took Solomon Kariuki for what he said he was – shy. In groups, he tended to stay at the back, contributing more smiles than dialogue during conversation. “I sit back, especially around people of higher classes. I am not the man to take control. When I was young, I would have my own cocoon when it comes to leading others. I have a phobia.” Why, then, is this reticent young man interested in being a mentor? For one, Solomon recognizes other youth in their protective wrappings, and knows how to talk to kids that seem unapproachably quiet. And second: Solomon is not the introverted person he describes – he is, like most of us, more than he seems.

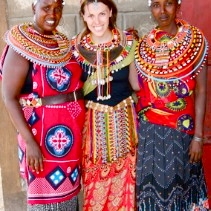

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

The mentoring program in Nakuru originally started at Solomon’s university as an investment club for students. Once they formed, members had difficulty identifying worthwhile investments, and it was Solomon who introduced the idea of mentoring. Solomon then selected 20 students (10 men, 10 women), many from the investment club, to learn more about mentoring – all of them then participated in Ripe for Harvest’s first mentor training. Each of the mentors picked two mentees; the mentees could be anyone – from the neighborhood, or a local school – the only guideline was to choose a person between 13 and 17 years old who is the same sex as the mentor. Abby Onencan, director of Ripe for Harvest, believes this age is a crucial time for young people to have a mentor. Solomon chose a neighborhood friend – a sixteen year-old boy – as his first mentor, and a second that was selected by a nearby high school (the principal chose students for the mentors that were going through difficult challenges in the hope that the mentors could straighten them out).

Solomon didn’t have any trouble talking with the neighborhood mentee; the other young man, selected by the school principal, was more challenging. In their first meetings, the mentee hardly made eye-contact with Solomon, and he often made up excuses for missing meetings. And this is where Solomon’s hidden talents of thoughtful observation and keen problem-solving came in. For both mentees, Solomon anticipated some awkwardness of meeting in a formal setting, so he made the get-togethers more casual. His neighbor loved rabbits, so on his visits Solomon helped him make a hutch for the pet rabbits, and sometimes they would go on walks looking for herbs that the rabbits could eat. They would find themselves talking about schoolwork or challenges with parents as they played with the rabbits or collected herbs.

The young boy who was slow to open up loved video games. He was often out of the house, spending his mom’s money at internet hubs with other gamers. Solomon was worried about how much time the boy spent in the arcade – and mostly concerned with the company he kept there – so he suggested to the mother that she buy the boy a bicycle, and she agreed. The boy loved the bike. He and Solomon would get together and repair it, and with Solomon’s guidance the boy went to the arcade less and less. Even after the bicycle was stolen, the boy didn’t return to playing video games; instead, he asked Solomon for help with his classes. “He listens to me, and has respect for me,” Solomon said. “I really appreciate that.”

I asked Solomon what qualities a mentor needed to have, and he told me about how he chose the mentors from his school. “I didn’t pick the popular people – I picked the quieter students because I could tell they cared about people.” These quieter students possessed perseverance, willingness to do voluntary work, were self-motivated and creative, and “they had an aspect of goodness” Solomon described, “like people who go to church. Basically, they were honest people – and approachable.”

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

And it was around these students that Solomon shone – rallying them together for meetings, motivating them to engage with their mentees in creative ways, and listening thoughtfully to their frustrations that sometimes arose during mentoring. Solomon was, despite his ideas about himself, the leader of this empathetic clan, calm and welcoming in every interaction I witnessed.

I asked Solomon what could be added to the mentoring program to strengthen it, and he didn’t hesitate: more training. Sometimes the challenges mentees face are serious, and the mentors are not sure how best to help them. The mentors also wanted more opportunities to be together – to learn from each others’ experiences and form a stronger support system between them. Right now, there aren’t enough funds to have events or trips for the mentors; there aren’t enough funds to continue the program.

Do you want to continue being a mentor? I asked Solomon. We have taken an afternoon hike and he and I were sitting on the porch of an abandoned house, away from the other mentors. He has become more animated as we talk, and with this question there is renewed steadiness and certainty to his voice: “we have made a commitment to these kids,” he said, “so we will continue mentoring them even if there is no more funding and the program ends. If we don’t, who will they have to talk to?”

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Nakuru, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Jul 31st, 2009