The representation of romance of the imagery of Prince Charming riding into the sunset with his bride-to-be traverses century, country, and culture (at least according to Hollywood!). Whether Westley and Buttercup or Aladdin and Jasmine; allow me to introduce to you the Romani couple as well.

The women in our quilting group decided upon an engagement scene for their Peace Quilt, as the family is a central value of their culture. However, now that the pieces are in place and the quilting is progressing, they’ve noted: We don’t have enough brown thread…there are more horses than people!

Belonging to the Kalderash group of Roma, the ancestors of these women lived as nomads, traveling by caravan and working as metalworkers, smiths and horse traders. The significance of gold coins stems from this period, in which antique equivalents of visas were secured by paying entry rights in gold. Upon entering a given territory, the traveling craftsmen were well regarded by the local populations for their unique skills. Such was tradition up until these women’s grandparents’ generation, when their families settled in Vilnius. Political and economic realities in Lithuania since then have challenged this way of life, with World War II devastating the population and the Soviet regime compelling settlement and “socially useful labour”. The forced change in lifestyle had adverse effects on the Roma, removing them from their fields of economic expertise and greatly contributing to their marginalization from a society that was, itself, struggling economically. Currently, very few Kalderash families in Vilnius are still involved in horse trading. Most earn their living collecting and selling scrap metal.

While the image of the nomadism of their forefathers continues to thrive in popular belief (as well as in the traditional nostalgia of our quilters), the families have certainly been settled here in Lithuania for a considerable history. But are they Lithuanian?

Their primary loyalty remains to family and the Roma community: the word Rom, inRomani, means ‘man’ of the Roma ethnicity, thus linguistically distinguishing Roma from non-Roma, and the preference remains to marry other Roma. Among Roma, Romani is still the language generally spoken, although the dialect has changed significantly over the past several decades. Society is united under an internal code of values and an internal legal system, to which members strictly adhere. Community well-being is of utmost importance and one of the most severe punishments is exclusion from it. Nevertheless, feelings of loyalty to the Roma community by no means detract from a loyalty to the territory and national traditions to which they have belonged for generations; in this sense, they are Roma, but of course they are absolutely Lithuanian as well.

Legally-speaking? As in accordance with the Law on Citizenship, they were born in Lithuania, to persons of Lithuanian descent, and would, thus, be Lithuanian citizens. But things are not always as they should be. Due to a tricky transition in legislationpending Lithuania’s independence from the Soviet Union, permanent residents of the territory were eligible to register for citizenship in the Republic of Lithuania between 1989 and 1991, provided they had two years of residence within the territory, a legal source of income, and a declaration of allegiance to the Constitution. However, this governed only until November 1991, when it was replaced with the new law of more stringent eligibility requirements.

Unfortunately, not everyone in the territory responded to the opportunity for citizenship at the advent of the Republic of Lithuania. There are several reasons for this: some did not meet the requirements, some did not see the advantage of formal citizenship, some were worried about declaring an allegiance that could be turned against them if the political situation were to become volatile again (keeping in mind that Lithuanians have suffered quite a bit at the hands of occupying powers). The primary reason in the Kirtimai settlement (to cite one particular community), however, was lack of awareness. Due to the existing marginalization of this community at that time, the initiative to inform them of the law was neglected.

Consequently, in order for stateless Roma to obtain Lithuanian citizenship now, it is necessary for these individuals, born and raised in Lithuania, to, in accordance with the Law on Citizenship, undergo the same process as foreign-born non-Lithuanian persons seeking naturalization.

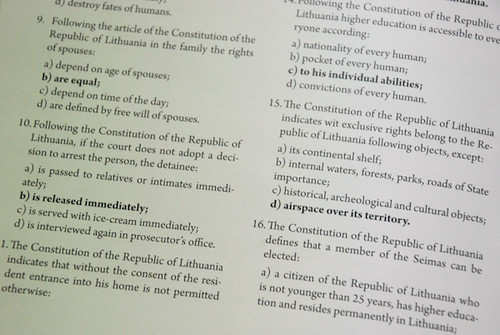

The process requires documentation certifying the right to habitually reside in Lithuania, legal source of support, an exam on the provisions of the Constitution, and an exam in the Lithuanian language. Despite the entitlement of descendants of Lithuanian citizens and descendants of those having been habitually present in Lithuania, as well as children born in Lithuania to citizenship, these naturalization requirements de facto preclude a population of Lithuanian Roma from now claiming their citizenship.

The vast majority do have residence permits (and thereby the right to habitually reside in Lithuania), whether temporary or permanent. This is very important as the residence permit opens access of persons to the most basic services. It is worth noting, however, that possession of no more than a temporary residence permit renders employment nearly inaccessible. A residence permit does not substitute for citizenship.

The requirement of a legal source of support is not so easily met. Procedurally, proof of a legal source of income requires a minimum of 10,000 litas in a bank account. Without legal employment, as is the case of more than 90% of Roma in Lithuania, it is all to easy to not have 10,000 litas in a bank account. Especially when banks also generally refuse clients they fear will not prove lucrative to the business. In practice, it is possible to overcome these obstacles if the public official examining the application decides to accept an alternate proof of the requirement. However, the whims of the individual public official should not be the deciding factor as to whether one whose family has resided in Lithuania for generations is eligible for citizenship.

While I will not go into details about Roma education in Lithuania quite yet, I will assure you that the last two citizenship eligibility requirements, a written exam on the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania and an exam on the Lithuanian language, are also problematic for a substantial population of Roma. Education remains a serious issue; 25.3% of Roma in Lithuania did not complete primary education or were illiterate at the time of the last published census. While the language exam may seem benign, in fact, more than one-third of Roma do not speak Lithuanian. One of the two groups of Roma of Kirtimai speak Romani and Russian. So do the Kalderash Roma in Vilnius, to which our quilting group belongs. In order to pass these exams, individuals must be able to read, write, and study in Lithuanian.

One final logistical consideration regarding the inaccessibility of citizenship to the Roma in Lithuania who missed the transitional citizenship opportunity is that obtaining any document requires time and money: to travel, to prepare, to apply, to take exams, to pay the associated costs. For those who have already been excluded on the basis of not having income, or that of not being literate, these will resurface as obstacles.

If it is such a hassle to obtain Lithuanian citizenship for these individuals, why is it important?

Holding a permanent residence permit entitles individuals to many state services; but far from all. Not having citizenship may bring disadvantages in employment, housing, health care, migration, and civic participation. Perhaps this final aspect does not appear to be of vital consequence; after all, the other aspects may directly impact physical well-being. However, these individuals do belong to the country, it istheir country, it is their past, and they do want to be involved in the decisions affecting their future. There is their dignity at stake in denying them their national identity.

Statelessness of Roma in Lithuania is much more a problem of adult generations. Children are meanwhile being registered at birth as Lithuanian citizens and future problems of statelessness appear to be being prevented. Nevertheless, those who do remain stateless are not insignificant as such. There needs to be more attention to the existing issue and legal means by which to rectify a situation caused by a public omission. Numerous actors are involved in responding to statelessness, including the Roma Community Centre, which offers preparation courses for the citizenship tests. Yet, the issue stems from a legal technicality and its remedy is, thus, not the responsibility of civil society to prepare individuals for the naturalization exam, nor of individual public officials to make exemptions to stipulated procedures, but is that of the state. The law needs to be accessible to the applicants, who, through no fault of their own, were excluded from their entitlement.

Posted By Elise Filo (France)

Posted Sep 9th, 2012