“I have nothing more to complain about, ever.”

This is the thought which crossed through my mind as we descended back down the dusty, reeking path into the slum. The green trucks hauling waste rushed past, leaving swirling eddies of rotting dirt and a foul-smelling, gritty wind to blow over us in their wake.

I was already not feeling well since waking earlier in the morning with a headache and slight fever; the intense sunlight that bore down on us at the top of the mountain of garbage had only worsened my discomfort, along with the un-breathable stench and the feeling of being coated in filth with every gust of the hot breeze. But above everything, what I felt the most deeply, and which has stuck with me since that day, was the sight of all these men, women, and younger boys and girls picking through the fetid piles of waste that covered the surface area of the landfill.

Zeeshan had brought us to the landfill, so I could attempt to photograph inside its boundary, and learn more about these waste pickers who persist in probably the worst working conditions [in my perspective as an outsider] that I’ve been witness to in this sector so far.

To get there, we first had to take a rickshaw to the area, getting off near the freeway and walking another 300 yards to the entrance of a slum that bordered one side of the landfill. I’d walked through a small section of a day laborers’ slum before, back when I first started working here in June and had taken a wrong turn on my way to work one morning…but that hadn’t prepared me for this. Blue tarps stretched across tin walls and poles, tied with ropes, and held down upon roofs with old rubber tires for weight; a wearied mother whose condition belied her young age sat under the shade of a tarp, staring into space with listless eyes while her infant nursed at her breast; other residents stared at us with vague curiosity as we passed; the smell of shit simmered in the noon heat, omnipresent just outside my nostrils which I was trying to keep clenched shut without anyone being able to tell.

I couldn’t get rid of the feeling that it felt wrong to be walking through the middle of these people’s homes—even if they barely resembled that—without being invited. I’ve never gotten comfortable with the way, following Zeeshan during our outings to the field, we usually just stroll through these villages or housing tenements, as if the absence of street signs or house numbers dissolves the residents of their rights to privacy and ownership.

On the other end of the slum, we emerged onto a gravel path leading behind more buildings to the entrance of the landfill. I was warned to keep my camera hidden until we reached the top, as photographs are not permitted inside the boundaries.

Nor are waste pickers legally allowed to pick waste from the landfill. To do so, they must pay a bribe to the owner each day. I have been instructed to leave the name of the area and the landfill out of my blog, for these reasons.

A man who lives in the slum and works at the landfill accompanied us—a contact of Zeeshan’s—and explained that waste pickers come here both from the slum and from the neighborhood of Seemapuri, which I’ve blogged about previously. As we climbed the road to the top of the hill of trash [acres of it], Zeeshan and I marked our surprise at not smelling anything… but upon reaching the top, where the wind could whip across the expanse of garbage without obstacle, we instantly ate our words with a mouthful of dust carrying the ripe perfume of decay.

I’d seen a few waste pickers from a distance on the walk up, almost blending into the gray-brown piles rising up from the road, but now upon the surface of the trash mountain, the reality of the conditions stretched clearly out in front of my view. Skyscrapers and high-rise apartment complexes and green manicured grounds stood in strange, shining contrast beyond acres and acres of garbage.

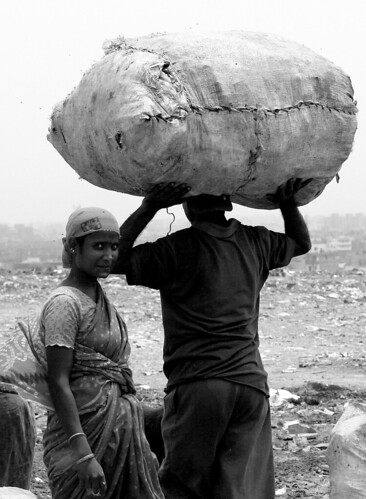

The landfill seemed to exist within a cloud of grey-brown dust that surrounded the acreage like a grimy bubble. Everything and everyone was covered with a layer of this grime, reminding me of a painting badly in need of restoration, as if you could swipe your fingers across the scene and reveal a clearer, brighter layer of color underneath. To my right and left were groups of people gathering trash into small bags that hung over their shoulders, tying up large sacks to take home for segregating, or resting under the shade of a battered umbrella to escape the blaring heat. In front of us, more waste pickers scavenged amidst the rumbling green MCD trucks, avoiding cows, stepping over mangy dogs, and ignoring storming flies as they searched for anything that might be valuable enough to sell.

I keep thinking about their hands. They were blackened, from fingertip to elbow, and I realized that this was layer which looked like soot or tar was the collection of the filth, dirt, grime, which had clung to their skin as they’d picked through the trash all day. It wore like gloves upon their skin.

Every half a minute, Zeeshan would either tell me to take pictures, or tell me to put my camera away. Increasingly frustrating. I explained that I wanted to ask permission to take anyone’s picture, that I felt very strongly about not snapping images that weren’t invited, and asked him repeatedly to explain to the waste pickers who I was and why I was here with him. I’m sure it appeared that I was some strange tourist, or maybe a reporter, and I could easily sense both the discomfort and unhappiness from many of the workers at the presence of my camera. Either way, this need on my end, to be sensitive and respectful was not getting across. I couldn’t see how I was going to come away with any useful photographs or interviews from this trip.

In the end, I snapped what I could, and we left with Zeeshan and our “guide” worrying over whether anyone had seen us taking photos, telling us to be sure we didn’t talk about the fact that these waste pickers pay bribes to the owner each day, lest he get in trouble. [I made sure that as long as I don’t name names, I can discuss it here]. I spent the next five days in the delirious haze of a raging fever and respiratory flu– hence my delay in posting this. Not necessarily caused by the trip, but likely exacerbated by the heat and dust encountered there. This definitely added to my reflection as the week went on.. as I got better, life returned to normal, things seemed manageable again. Whereas the lives of the people I encountered at the landfill will continue to exist in those conditions. I can’t stop thinking about the girl I tried speaking to, right before we went back down. I didn’t have any help in translation, and she wasn’t inviting conversation either, but the image of her is fixed in my mind: sitting upon a pile of crusty rags and plastic trash, staring out at the acres of waste that are her source of livelihood. That IS her normal. She, along with the other youths we saw working there, does not attend school, and has little opportunity to do so. That is her experience every day, without much hope of anything improving.

I can’t forget her face. It is experiences like this which have illustrated for me more clearly how environmental and social injustices merge; it is here where the outcomes stemming from misplaced government agendas, from social stigmas, from the cycle of poverty and environmental degradation, manifest in the lives of those who are forced to bear the weight of the problems…I wish I didn’t have to gain my understanding through witnessing the misfortune of others.

Below are some other images from the visit.

Posted By Mackenzie Berg

Posted Aug 1st, 2008

691 Comments

iain

August 12, 2008

The photos on this blog are spectacular… The description of the sensory assault also very powerful. But the bit I like best is your concern at walking through their homes… Now I want to know more about exactly how these remarkable people live in this muck…Great job.