The CPI team is driving into the sunset, our van running parallel to five zebras, when the Director, Hilary, breaks into “Edelweiss” from The Sound of Music. Click here to listen! The fading light refracts in the cyclone of dust that surrounds our speeding Land Cruiser, driven by our captain, Francis. To his left in the passenger seat rests Iain, the founder and director of The Advocacy Project, whom I have to thank for my position this summer.

Iain is visiting Kenya for one week to observe CPI’s projects and lay some groundwork for the grant proposal I’ll be writing this summer. In honor of Iain’s visit, our team is traveling north to Samburu County to visit the communities served by CPI’s peacebuilding programs. The last five years of CPI’s work in conflict resolution and peace promotion between the Samburu and Pokot tribes outside Maralal have served as their poster child. We are on our way to check out this model of success that transformed two pastoralist communities mired in perennial violence. Maralal, a small town found about seven hours north of Nairobi by car, is our current destination.

I am tucked in the back of the van along with Hilary, Monica, Jane, Purity, Michael, all of our luggage, and four boxes of water. The seats in the back have been rotated into two long benches along the sides of the van so that the six of us face each other, knees knocking back and forth with pinball zeal as we navigate the ruts of central Kenya’s unpaved backroads.

Roadtrip Snacks: Men selling their produce along the road charged our car, plunged their burnt ears of corn like blades through our windows, and began a comical corn sword fight with each other as they vied for our attention. We bought a dozen charred cobs to munch on.

The bouncy ride has been a musical one. Our shaking voices rattle throughout the vehicle, which feels more like a bucking mechanical bull than a car. When we pulled out of Nairobi, Monica had suggested a prayer to bless the journey. Suddenly everyone around me—except Iain, another unknowing mzungu—struck up a perfect harmony and began singing in Swahili. Click here to listen!

The way in which they broke into song without trepidation was entrancing; their voices convinced me that some superior force would see us safely to our destination. Hilary’s bass, a voice drawn deep from the belly, reminds me of Ladysmith Black Mambazo in “Homeless” off Paul Simon’s Graceland album. The long journey warranted several sing-a-long sessions, including The Sound of Music, Fiddler on the Roof, and The King and I soundtracks, as well as a song about the Mississippi River that I had never heard. If you want to feel like a thousand worlds have collided, listen to a group of Kenyans sing Charley Pride’s “Roll On Mississippi” while driving through a conservation full of giraffes, zebras, and wildebeests.

We roll into Maralal at dusk and settle into our $6/night rooms at the Morris Guest House, which will serve as our basecamp for the next few nights while we travel to remote villages during the daytime. I’ve only been with CPI for a few days, but I’m thrilled to already be meeting their beneficiaries and witness firsthand their direct and indirect impact. I’d like to briefly outline their model to give you an understanding of how CPI utilizes children’s participation in peacebuilding as a catalyst for societal change. Peace is not a new concept. Hundreds of thousands of writers have gabbed about it. Centuries of philosophers have pondered it. Generations of activists have picketed for it. John Lennon and Cat Stevens sang about it. There’s seemingly little space left to rethink peace, yet CPI has constructed a fascinating model that has contributed to peace (not a single death!) between the Samburus and Pokots around Maralal in the years since their first activity there in 2012.

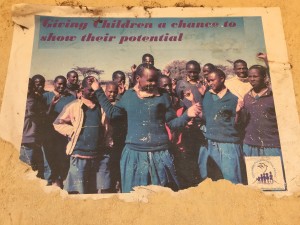

CPI’s process for interethnic peacebuilding between children of differing tribes begins with peace camps. CPI first targets two feuding tribes and establishes a perimeter around the population of interest. The schools in this assigned area become the entry point into the community and teachers are chosen and trained as partners. After establishing strong relationships with the schools, approximately 300 children from the two tribes are brought together for a three to five day peace camp. Parents are often nervous about these interactions and fear for their children’s safety amongst members of the other tribe, but the schools’ administrations recognize the strength of CPI’s model and promote the advantages of peacebuilding.

Over the course of the camp, the children engage in teamwork, field games, and confidence building activities that allow them to forget each other’s differences. By the end of the camp, children see each other as friends with more similarities than they could have anticipated, rather than as perceived enemies.

At the peace camp’s conclusion, children from each community are paired in a process called “twinning.” As twins, the friends keep in touch after the camp and exchange small gifts. Parents are drawn into the equation when their children return home and tell them of their surprising new relationships. When a child asks his or her parents for money to purchase a gift for exchange, their parents become subliminal sources of support for interethnic friendships.

The next step is a holiday exchange program, in which a child will go stay with his or her friend for eight days. A Samburu family, for example, will welcome their child’s Pokot friend in their home and treat him or her warmly. When the Pokot child returns home alive and well, and often with the gift of a goat or clothing, the parents are shocked to hear of such hospitality. Fears and assumptions of hatred in the adults’ hearts and minds are assuaged by their children’s love for their new friends.

The next stage includes home stays in which a child brings one parent to stay with the friend’s family. This exchange happens twice so that both families have the enriching opportunity to experience the other tribe’s lifestyle and homestead. Over the course of about a year, these families discover each other’s humanity and deepen their relationships. The bonds grow and create a ripple effect of peace and interdependency within the communities. Through children, the parents, elders, and warriors come to recognize their enemies as potential friends and trading partners. Economic incentives for peace are provided in the final stage called Heifers for Peace, in which one cow is donated for two families from different tribes to share after about three years of committed friendship.

Pastoralists depend on livestock. Giving two families a heifer significantly impacts their livelihoods, particularly during the current drought that is killing off herds.

CPI doesn’t just aim to establish ceasefires and prevent violence. They understand that sustainable peace depends on nurtured relationships and changed behaviors. Even in past peacetimes there were not friendships between the Samburu and Pokot. Peace between communities founded solely on an absence of interethnic violence runs the risk of reescalation; but the longevity of friendships, economic exchange, and social integration are far more conducive to enduring peace. Look for my upcoming blogs on my experiences in the field and my interviews with Samburus and Pokots who testify to the power of CPI’s peacebuilding program!

On the road to peace with Michael, a Comboni Missionary Brother who is interning with CPI this summer.

Wondering what you can do to bring peace to Kenya? Please click below to contribute to our work with pastoralists through Global Giving!

Posted By Talley Diggs (Kenya)

Posted Jun 14th, 2017

7 Comments

Kathleen Conroy

June 14, 2017

Talley – I am finding the work of CPI so fascinating. And you are having such valuable experiences there. I look forward to meeting you in July and hearing more. Kathleen

Sandi Filer-Gothie

June 21, 2017

Dear Talley, Thank you for sharing your wonderful experiences with me! I feel like I’m participating in your journey!

Peggy Revelle

June 27, 2017

Talley, Your Aunt Sandi, my dear friend and next door neighbor shared your Blog with me. Aunt Sandi speak highly of you and I can understand why. I am blown away and speechless at your writing abilities (making me feel like I am here); the priceless experience you are having and the proven results from the CPI program. You are definitely making a difference in this world and I thank you. Take care. Peggy Revelle