The heat of the mid-morning sun had wiped away any sensation of chill in the air. In mere hours, the temperature had climbed more than ten degrees Celsius. While the children were enjoying a group activity that employed old newspapers as fabric for an inter-ethnic fashion show, I remained nostalgic of the cooler hours and hid underneath the tallest tree I could find. Hiding from the sun was the least I could do for my body. My pink forehead and nose inspired the children to giggle at me, seeing me as some grotesquely painted clown.

While I hid underneath that acacia tree, on that final day of the Zivik-CPI Kenya Peace Camp in the village of Bendera, just a short distance from the town of Baragoi, I met with a young man named Joseph Longeri Nangodia. I initially met him briefly as I sprinted to the store room to gather my camera. I shook his hand and said hello as I passed, completely unaware of who he was. I met him again as the “fashion show” begun. He sat next to me and we briefly exchanged a few niceties as I showed him the cumbersome camera that I bought just months before. However, our conversation was cut short as I jumped to action to snap photos of the “show”.

While on my knee for one photograph, Monica Kinyua (the CPI Kenya Deputy Director) asked me “have you met Joseph?” Not knowing the story of Joseph, I responded all too quickly, “yes”. Aware of the shortcomings of my response, Monica merely told me that he was a beneficiary of the 2016 Peace Program and maybe I should talk to him a bit more.

Before lunch I asked Joseph if he would like to find a place to talk about his experiences. His response was a bright smile that contrasted with his sad eyes and, in a soft voice, he said “sure”.

We quickly found a spot that was in the shadow of the store room and sat on the cold concrete (a welcomed respite from the overbearing heat). While our conversation begun by talking about his schooling, his struggle to continue his education begged the question of his past.

In a matter-the-fact manner he told me his father was killed in 2015, when he was merely 13 years old. His father was killed in a cattle raid that claimed much of his family’s wealth as well as his father’s life. He explained how he was home during the raid, while his father had taken the cattle out to graze. While he had heard the gunshots, he didn’t realize that his father had died until his mother was contacted by the police later that evening.

The raid left him fatherless and his family struggling to make ends meet. His mother began to sell charcoal in order to bring food back to the home. The constant challenge to gather enough income for basic necessities prevented Joseph from feeling anger or truly expressing his sadness. He was distracted by the needs of the present. The survival of the family was at hand, and such reflection on loss was understood by Joseph as “self-indulgent”.

Luckily, Joseph had a blossoming talent up his sleeve. His talent could be a way out of poverty as well as his therapy. This talent was his art.

Less than a year after the raid that took his father’s life, Joseph attests that the CPI peace program helped give him a sense of peace and solidarity with those who have also been harmed by cattle raids. Beneficiaries who had encountered trauma due to persistent conflict, on either end of the Turkana-Samburu ethnic divide, allowed Joseph to begin to digest the events of a year prior.

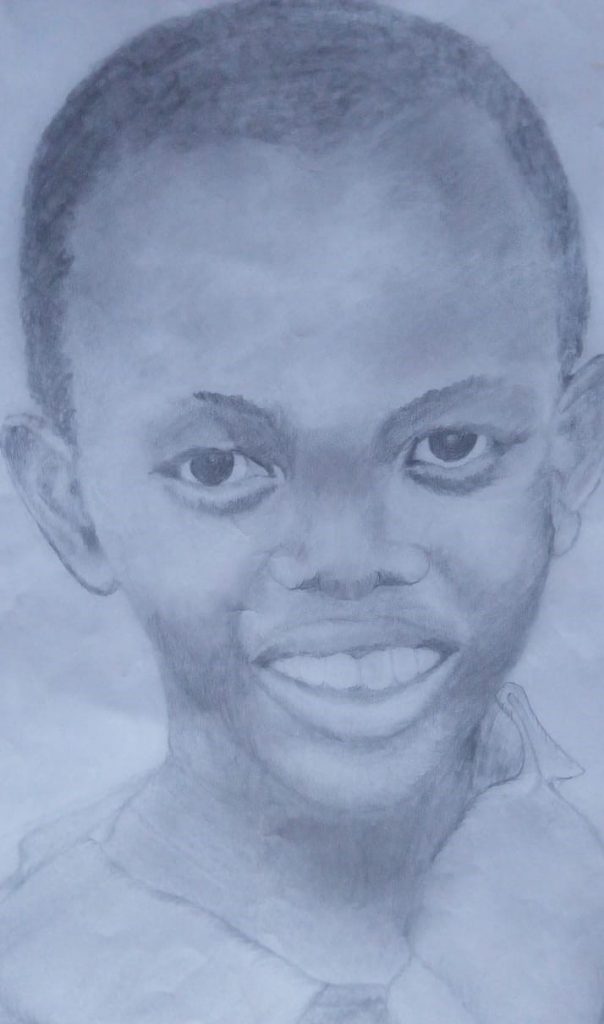

Joseph’s artwork also helped. From early on, Joseph had a talent for sketching. He would find him self drawing pictures after school as a hobby. Following the short-lived program in 2016 (where funding shortfalls prevented the fruition of the project), he was able to begin one journey of handling the trauma of his past. Simultaneously, he would use his love for art to address the long journey away from poverty.

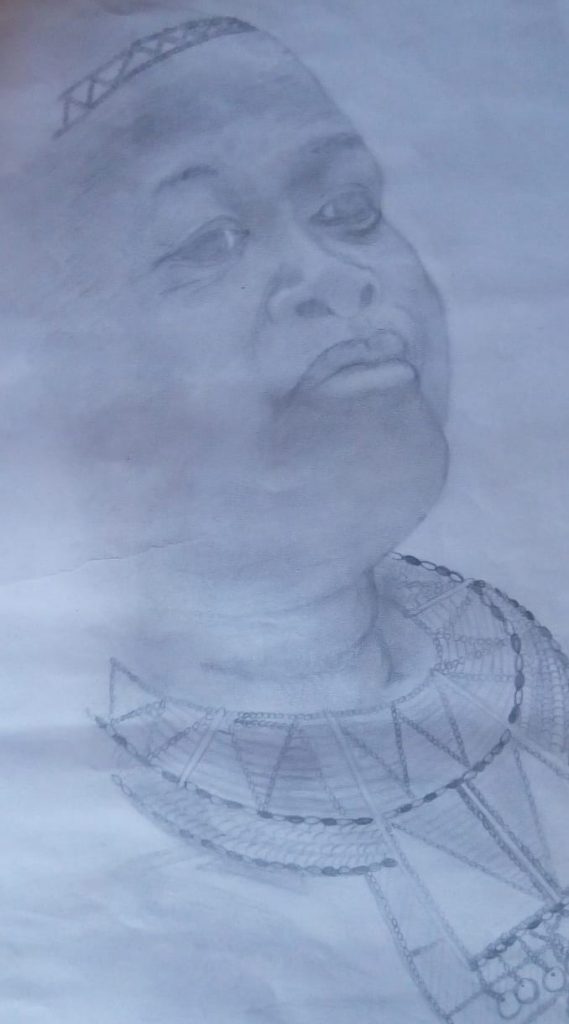

He began the journey by drawing sketches for his science class. A teacher had taken notice of his ability and asked him to create images to help instruct students. This simple gesture gave him confidence to begin creating cultural images and portraits. Some of the portraits have been of local political leaders in traditional garb. Some of the portraits have just been of children he has seen in his neighborhood. And, some of these portraits have been sold for a modest price to bolster his family’s income.

With some recognition of his talent in the remote town of Baragoi, he hopes to go to the University of Nairobi and refine it further. Nonetheless, the cost of attending university is an immense hurdle. Joseph acknowledges that “only those from good schools and money get to go to university and study fine arts”. Despite this, not having formal training has given his art a sense of originality, injecting a bit of himself into every drawing. If you have any interest in helping Joseph overcome this hurdle, please contact Children Peace Initiative Kenya (link: https://cpikenya.org/ / info@cpikenya.org ).

And, if you would like to support the current Zivik-CPI 2019 Peace Program in Baragoi, please visit our GlobalGiving page.

Posted By Benjamin Johnson (Kenya)

Posted Jul 16th, 2019

5 Comments

Abby Lahvis

July 17, 2019

I loved this blog! Such an inspiring story about forgiveness and perseverance. I look forward to more profiles.

rachel wright

July 17, 2019

I loved hearing the perspective of someone who has gone through one of CPI’s peace camps. I hope Joseph is able to turn his passion for art into a career!

Emily

July 18, 2019

These sketches are really advanced! I do some sketching myself, and even after taking a class I’ve never produced something like this. Please send more!

Sam Nass

July 23, 2019

Being able to draw like that without formal training is kind of like having a superpower. Someone get this kid into the Louvre!

Iain Guest

August 11, 2019

Nice story and good reminder that cow wars have a deep impact in families and societies.Joseph certainly is a good artist!