How it began

Visit the Profiles tab to meet the individuals cited on this page

Partners in WASH: Kathryn Dutile (2014) laid the foundation for the toilet project while working at GDPU.

This startup began with a story. In 2011 Rebecca Scherpelz wrote a powerful blog while serving as an AP Peace Fellow at the GDPU in Gulu. She noted that the only accessible toilet available to the public in Gulu was at the GDPU office, and invited readers to consider what this meant to people with special needs:

“You don’t have time to head to GDPU and spend nearly an hour of your day on the road. Instead, you opt to use one of the public bathrooms, maybe paying 200/=. Since it is a public pit latrine, it’s likely incredibly filthy from who-knows-what by who-knows-who; since your disability does not allow use of your legs, you slide to your hands and knees to crawl into the latrine and balance yourself as best as possible before crawling back outside, climbing back on your wheelchair, and returning to work.”

The next Fellow to serve at GDPU, Dane Macri (2012), followed up with more blogs along the same lines. These graphic descriptions served as a call to action. GDPU identified the Gulu Bus Park as an ideal location for an experimental toilet. Helped by Dane and Rebecca, AP raised about $3,000 and recruited Peace Fellow John Steies to manage the project. After many delays and mistakes by the contractor it was not until October 2014 that the toilet finally opened. Our 2014 Fellow Kathryn interviewed people with disability who frequented down-town Gulu and found that 80% had used the toilet and felt “safe” as a result.

Unfortunately, their relief was short-lived. Within a year the toilet had been vandalized and closed. With the wisdom of hindsight, we had made some classic mistakes. The design (a flush toilet) was too sophisticated. The location was too exposed. No one was prepared to pay for upkeep or maintenance. Finally, we were doing the government’s job – in spite of long discussions and an MOU, the Gulu town council was not prepared to take on the maintenance. In short, the community had no real stake in the toilet – a recipe for vandalism and neglect.

At GDPU’s suggestion, we then turned to schools. Kathryn helped Patrick, the GDPU coordinator, to survey 12 primary schools and found the toilets to be in terrible shape. This was particularly difficult for students with special needs, as Rebecca had warned. When AP visited the Tochi School we were told that enrollment had fallen sharply. Christine Aloya, the principal, was deeply pessimistic.

“When nature calls and society hangs up.” Rebecca’s blog in 2011 exposed the lack of public accessible WASH facilities in Gulu and served as a call for action.

At the principal’s request, GDPU and AP agreed to install a new toilet at the Tochi School, some way from Gulu town. Our 2015 Peace Fellow Josh Levy from Columbia University, launched a crowdfunding appeal and raised $4,030 from 45 donors. Josh helped Patrick to hire a contractor and install a new concrete structure with two accessible toilets – one for girls and one for boys. Patrick and Josh also introduced training in inclusivity and hygiene for staff and students and purchased soap and water tanks.

The following year, Peace Fellow Amy provided us with a reality check. Amy surveyed remote ten rural schools with Patrick and recommended that the next toilet should be installed at the Ogul School. But she also reminded us that disability took many forms and that not all can be addressed by accessible toilets. GDPU decided to hold the Ogul project over to 2017, giving us time to reflect and seek more funding.

AP visited the Ogul School with GDPU in June 2017. Once again we found toilets in an atrocious condition. We worked with our Peace Fellow Lauren to launch a second appeal on Global Giving and secured a grant through the online marketplace Givology. Helped by scores of parents, Patrick and Lauren were able to install four new toilets at Ogul.

The next project targeted Awach Central School, with 911 students. Our 2018 Peace Fellow Chris raised $4,550 through crowd-funding and secured a generous grant from Water Charity. Chris and Patrick put out bids and oversaw the renovation or construction of 13 new toilets. Iain from AP returned to Gulu in November 2018 and visited the three schools with Patrick from GDPU. Some of the material for these pages comes from their report. The rest comes mainly from the blogs of Peace Fellows.

Challenge

Visit the Profiles tab to meet the individuals cited on this page

Desperation move: Auma Prisca Oyella, principal of the Ogul School, salvaged these portable toilets from an abandoned refugee camp. Many of her students refused to used them. (June 2017)

This startup takes place in one of the most intimidating environments on earth – school. In addition to the normal pressures facing students anywhere, primary school students in Gulu District have to contend with shockingly poor water and sanitation. This page looks at the context, symptoms, causes and impacts through the four schools served by this startup between 2015 and 2019.

Legacy of War

Everything in Gulu has to be seen against the backcloth of the Lord’s Resistance Army, which spread terror across northern Uganda between 1988 and 2010 and left deep physical and emotional scars. One former student, Olympia, told our Peace Fellow Chris in 2018 how she had lost her hearing after fleeing countless attacks by LRA rebels. Chris writes: “She describes nights spent sleeping in the dirt, hidden under tall grass, the air filled with the sounds of mosquitoes and screams. The last vivid sounds she remembers are people crying and gunshots. ‘Even now, if a motorcycle [backfires] people’s hearts start pumping. Some drop down; others just run without looking back. I still remember everything.’”

Years later, the impact of the war is still felt in schools. As late as 2014 students at the Tochi School who had been abducted by the LRA were being bullied by classmates.

The WASH crisis

In designating November 19 as World Toilet Day, the UN General Assembly noted that one in three people do not have a basic toilet, and that almost 2,000 children die every day from preventable diarrheal diseases. Visiting the schools of Gulu it is not hard to see why.

AP has struggled over the years to describe the state of school toilets in Gulu without resorting to hyperbole. Peace Fellow Chris described his first visit to the Awach toilets in a 2018 blog as “sensory overload.” He writes: “I have never seen that many flies in one place. This latrine was past full, on-the-verge of overflowing full. There were maybe six inches from the hole to the top of the waste. One heavy rain is all it would take to turn this latrine into a cholera outbreak.”

Some toilets at the Abaka School are so primitive that teachers fear small children might slip through and drown. (November 2018)

The same has been true of many other schools visited by GDPU and AP. At the Ogul School in 2017, boys were using derelict toilets from a long-abandoned refugee camp which were on the point of collapse. A similar sight awaited GDPU and AP at the Abaka School, where GDPU will work in 2019. An international agency had built four toilets, but two had long closed and the two that still operated had been declared a health hazard by a government inspector. Desperate parents had built two makeshift toilets near the school which were still occasionally used, even though there was a real risk that smaller children may slip through and drown. Teachers at Abaka were reluctant to forbid the use of these toilets because it might force children to retire to the tall grass where they could be bitten by snakes.

The challenge of sanitation is, of course, linked to water. Without water, there can be no hand washing. Most schools have a borehole and hand-pump on their grounds, but in many cases these are also used by the local community. World Vision installed a hand-washing tank outside the Tochi School toilet, but it was vandalized within a day and never replaced. A large water cistern at the Abaka School was abandoned after villagers stole the gutters that fed the cistern with rainwater. Faced by this, many schools have thrown up their hands and given up. The Abaka staff were even unwilling to buy soap.

Disability

This startup was launched in 2015 on behalf of students with a disability for a reason. According to the 2011 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey, nearly 12 percent of all students under the age of 19 had some form of disability.

As Rebecca’s 2011 blog suggests, attitudes towards disability in Gulu can range from indifference to hostility. Patrick from GDPU has said that the Acholi culture can be “hostile” towards disability: “Parents with a disabled child will sometimes pray for the child to die.” Even the local language about disability is seen as insensitive by some people with special needs.

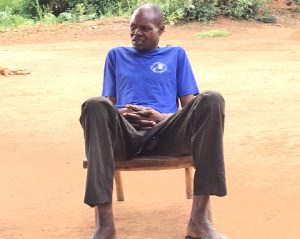

Students with a physical disability need ramps, handrails and a strong dose of determination to use school toilets.

The impact of the WASH crisis has been severe on students with a disability. Before GDPU constructed a latrine at the Ogul School Andrew, 8, a quiet-spoken student at Ogul who had a problem with his knees, told us that he could not squat in the makeshift toilets. He was also afraid that the floor, which was infested with maggots, would fall through. Many of his classmates stayed away from school altogether rather than use these contraptions, or returned home to use the fields that were at least familiar.

But while the lack of accessible toilets may be particularly difficult, students with disability face other obstacles. As our 2016 Peace Fellow Amy noted, accessible toilets will do little for students with a hearing difficulties. None of the ten schools surveyed by Amy and GDPU had a teacher who knew sign language.

Bullying

Anyone who has attended school knows that bullying comes in all shapes and forms. In the primary schools of Gulu, it is often directed against students with special needs. GDPU surveyed 12 schools in 2014 and was surprised to learn that after toilets, bullying was most on the mind of such students. Some described their concerns through poignant drawings. It was the same story at the Tochi School. Nancy, 14, has a mild case of cerebral palsy, which can be triggered by malaria. After she took a week off to be with her parents the other girls teased her for having got married. Teachers calmed Nancy’s nerves by giving her knitting.

Looking back on her time at Tochi School in 2018, Nancy remembered how she had been mocked for her misshapen arm: “’Some people have disabilities that you cannot see. (They) are the lucky ones. Children would see me and mimic my arm, which really hurt me.” Ivan Olanya, who had studied at Tochi with Nancy, told us in 2015 that he, too, had been mercilessly bullied. Some of Ivan’s classmates had even smeared feces on the toilet grab bars, in an attempt to force him out of school. Christine, the school Principal, said that they were jealous of Ivan’s good grades.

At the Layibi School in Gulu Town, AP was told that some blind children were prevented from sitting at the front of the class by other students, and were unable to afford glasses. Opio, 11, told Kathryn that other students used to push him out of his wheelchair until GDPU fitted him with crutches. When another student shouted in class because she had a mental illness, the other students beat her up.

Nancy, left, was bullied at school because of her arm. Other students smeared feces on the toilet handrails in an effort to force Ivan to leave the Tochi School (2014).

Without the support of a sympathetic school community, such students must fall back on their own guts and determination. Jennifer was admitted to a leading school for girls in Gulu Town without the school authorities being aware that she used a wheelchair. As she told Peace Fellow Kathryn, Jennifer’s classmates spent so much time carrying her around in her wheelchair that the school administration came to see her as a disruptive presence and asked her not to return to the school. GDPU intervened and Jennifer went on to secondary school and Uganda’s top university, Makerere, in 2013. She now runs a small business and sits on the board of the Gulu Women with Disabilities Union. Like many children with disabilities, Jennifer was nothing if not persistent.

The parents of children with disability are also under pressure. Trudy, 14, suffers from a mild visual impairment and she told 2018 Peace Fellow Chris how her mother had struggled since her father had died of AIDS. What does that struggle look like, asked Chris? “Like one meal a day and missing school to work on the farm.”

Money

The government of Uganda prides itself on providing free and universal primary education and on respecting the rights of persons with a disability. Gulu shows it is hard to turn the theory into practice.

The main reason is money. Under the system, district education officers are allocated funding based on their needs and numbers, but the amount is never enough. Cesar Akena, the DEO in Gulu, received 11 billion shillings ($2,952,070) in 2018, of which 9 billion ($2,415,000) was earmarked for salaries. This left $536,740 to cover the needs of the entire district. Given that a new toilet costs 26 million shillings ($6,980), Mr Akena is only able to fund infrastructure projects in four of the district’s 65 primary schools in 2019.

The schools themselves are in no position to pay for new buildings. The Ogul School received 4.5 million shillings ($937) from the government in 2018 – less than a third of the school budget ($3,757). The burden of making up the difference usually turn to parents (see below).

Private Agencies, Inconsistent Standards

Water tanks are used for hand-washing and are vital to a school’s hygiene, but many school tanks and gutters are vandalized by villagers.

As the government has withdrawn from funding WASH projects the space has been filled by international NGOs. While they have done much good work, the projects visited by AP and GDPU rarely met government accessibility standards. At the Tochi School in 2014 we found that the ramp and door to an accessible toilet built by World Vision were too narrow for a wheel chair. One of the two water tanks was too high for students to reach. When Peace Fellow Lauren visited Ogul School for the first time in 2017 she found that there was no path leading from the school to the girls’ toilets, which were supposed to be accessible. Nor were there handrails to help students with physical disabilities.

With several different agencies working independently from each other, it is not surprising that the technical standards are inconsistent. There is general agreement that latrines should be drainable. If this is not done a new pit will have to be built when the latrine fills, taking up valuable agricultural land. Meanwhile the old pit remains a health hazard. The government is aware of this environmental threat but this did not stop the Gulu sub-county authorities from installing a non-drainable toilet at Ogul School in 2017. We encountered other examples of inconsistency. The Ajulu School had four excellent toilets for girls, but no agency had funded the boys’ toilets, which were missing doors and had been assembled in desperation by parents.

Sustainability is another challenge. None of the agencies that had worked at schools visited by AP had returned to maintain or repair the WASH facilities they had installed. They might reasonably reply that the government or school should take on the task of maintaining the toilets, but this had not been agreed with these schools. After installing toilets at the Abaka School, the agency ACTED promised to return, but teachers say this has not happened.

Teachers

Many school classrooms lack doors and windows, but the Gulu district government can only afford to fund 4 school projects in 2019 and has to choose between toilets and classrooms.

Teachers influence attitudes towards disability, personal hygiene and discipline at schools. As in any system, the attitude of teachers and administrators in Gulu District can vary wildly from indifference to enlightenment.

The Principal was often absent from the Abaka School in 2018, and this left his staff rudderless and demoralized. Layibi Central School had a special needs teacher in 2014, but this did not stop other teachers from using disparaging language about students with disability. Students with HIV were categorized as “disabled.” Peace Fellow Josh described his frustration after visiting one school: “The teachers said that there was one student who everyone called by his nickname, ‘Mulema.’ That nickname literally translates to ‘the one whose leg does not function.’ The teachers claimed that the student was perfectly fine with this nickname and that they didn’t even know what his real name was.”

Community Vandals

Everyone loves the idea of a community school. It comes as an unpleasant surprise to find that communities are both a cause and casualty of the WASH crisis in Gulu.

Part of this is due to the lack of funding, described earlier. The burden of making up the school deficit falls squarely on parents who pay in two ways – directly through fees and expenses for their children, and indirectly by contributing to the Parent and Teacher Association (PTA). In 2017, Charles Nyeko, head of the PTA at Ogul School and father of four pupils, spent around 250,000 shillings ($68) a term on uniforms, exams, lunch and exam fees. He also paid a “development fee” of 11,000 shillings a term and another amount to the PTA. In all, parents contributed 8,900,000 shillings to the Tochi School annual budget in 2018 – more than twice the amount received from the district government (4.29 million shillings). This is a major commitment for farming families, whose income is often irregular.

Students with disability, particularly those with a hearing impairment, have much more to worry about than toilets. Many schools do not offer sign language or specialist teachers.

Beset by pressure and uninspired by poor school leadership, many parents become apathetic and resentful. In some cases, they add to the WASH crisis. During her survey of 12 schools in 2014, Kathryn found that local villagers routinely use school latrines and borehole. The path from Tochi village runs through the school grounds, which explained why the water tanks at the Tochi School were vandalized within a day of being installed. (For good measure the vandals also defecated over one tank.) Three years later, thieves were still entering the classrooms at Tochi and stealing school supplies. Villagers at Abaka have stolen the gutters that deliver rain to the water tank and enable hand-washing.

The fact that these vandals are probably also parents is disconcerting. But it is hardly surprising given the level of poverty in villages and the fact that many schools – like Tochi and Ogul – have very few windows. In addition, the lack of finance makes it harder for principals to hire watchmen.

Impact

The most dramatic impact of the WASH crisis on schools has been a sharp fall in enrollment. Other factors can contribute – for example some girls will leave school in grades 5 and 6 to get married. But teachers have been quite explicit about the link between WASH and enrollment. Christine Aloya, the principal of Tochi School in 2015, said that the poor state of toilets was pushing parents to seek out other schools. Auma Prisca Oyella, the Ogul principal, also blamed toilets for a fall in enrollment at her school, from 560 students in 2016 to 375 in 2017. Principals like Ms Oyella dread such declines because they reduce school income.

Most school costs are born by parents. This is a heavy burden for farming families.

The link between WASH and attendance is less clear. Attendance at many of these schools is often low at the start of the school term, but it picks up as the exam period approaches because students cannot advance without exam results. Principal Aloya at Tochi said that students tend to stay home during periods of food shortage and heavy rain. Christine Okot, the Ogul principal in 2018, said that many children leave school to work on the harvest. But both principals said that these children would eventually return.

Teachers understand that poor WASH facilities cause poor hygiene and contribute to sickness, but not all of them have taken steps to change this. As noted above, the Abaka School does not even purchase soap (which costs the equivalent of 10 cents a bar) or toilet paper, let alone delegate students to keep the toilets clean. Few schools appear to even monitor the health of students, assuming that this will be done by parents. Poor WASH undermines discipline as well as hygiene.

Among its less visible impacts, the WASH crisis has also widened the gap between urban and rural schools. Rural schools are always the last to benefit from new aid projects or government services, and incomes are always lower than in towns. When AP visited Ogul in 2017 we were told that the district nurse had made one visit in the last six months. Rural schools also have a much higher ratio of students to toilets.

There is also inequity within schools between boy students and girls, who need more privacy while menstruating. It is hard to find privacy inside a stinking, collapsing toilet. Even if they are not intended, these examples of discrimination are another reason to be concerned by the WASH crisis.

The Community Response

Visit the Profiles tab to meet the individuals cited on this page

What does a community-based approach to WASH look like? This page seeks to explain through the eyes of those who are directly affected.

Construction

Welcoming the new arrival: Hundreds turned out for the opening of the new toilets at Tochi School in August 2015.

GDPU’s first goal is to make sure that its WASH projects meet government specifications. This calls for professionals. It also helps if the contractor is from the community. After being badly let down by the contractor at the Bus Park toilet in 2013, GDPU asked for three bids before starting work at the Tochi School two years later. But even competitive bidding does not guarantee success. The Ogul School project was close to completion in August 2018 when the contractor suddenly dropped out of sight. Luckily, the team foreman Ronald and Abinga the welder stepped up and filled the gap, prompting our Peace Fellow Lauren to describe them as “accessible heroes.”

GDPU struck gold again the following year when the construction team at the Awach School emptied the foul latrine pit in two days and completed the 13 stances on time. One reason was that the contractor, Charles Kennedy Akena, had himself studied at the Awach School as a child.

Understanding the importance of hand-washing, GDPU has installed water tanks at the three schools and offered to provide soap and toilet paper for the first year, after which the schools and parents would take over. Still, the tanks continue to present a tempting target for vandals. After GDPU rebuilt the gutters and water tank at the Tochi School and put a lock on the tank, vandals broke the tap. This created a problem because the new accessible toilets were made to be washed out after use and the water would now have to carried from the school bore-hole. When Patrick learned of the problem he designed a folding seat for students with special needs and had the latrine pit widened.

The School Community

GDPU has been fortunate in the three school principals it has worked with. Christine Aloya (Tochi 2015) Auma Prisca Oyella (Ogul 2017) and John Bosco (Awach 2018) have embraced GDPU’s WASH projects with enthusiasm. This has spread to the entire school community – staff, pupils and parents.

John Bosco, principal of the Awach School, briefs parents on the progress of the new toilets (2018).

Ms Oyella, at Ogul, had long fretted about poor hygiene at her school. She was the one who led a group of parents to an abandoned refugee camp and brought back the portable toilets. Fully aware of how awful they were, Ms Oyella jumped at GDPU’s offer to install new toilets in 2017. Her counterpart at the Awach School, John Bosco, also needed no persuading. Mr Bosco has overcome a mild disability, which is why his school has a higher than average number of students with special needs. Several said they had enrolled because they knew the headmaster would make them feel welcome.

Head teachers like Mr Bosco ensure that hygiene is viewed as a responsibility of the entire school community. After visiting one school, Peace Fellow Josh was dismayed to learn that late students were punished by having to clean the school toilets. This, he warned, would turn them against the whole notion of hygiene. Attitudes have changed since the new toilets were installed. In late 2018, the Ogul principal explained with pride how her students clean all toilets at the start of every school day as part of their duties.

Teachers need to be co-opted if the school culture is to be changed and with the school principal on board this is an easy sell. Patrick and Josh developed a 2-day training for teachers known as the Game of Life, which proved to be so successful at Tochi that they took it to other schools. Peace Fellow Amy, who accompanied Patrick to two schools in 2016, felt that the success of the training was due to Patrick’s skills as a teacher and willingness to discuss his own problems: “Patrick walks with a limp from a reaction to a vaccine as a child and has overcome many barriers to get to where he is today. It brings a new meaning to the training and I think to the teachers, to see someone in front of them with a disability.”

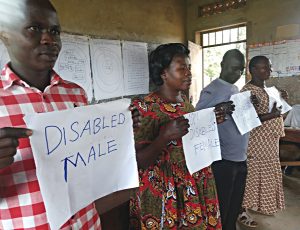

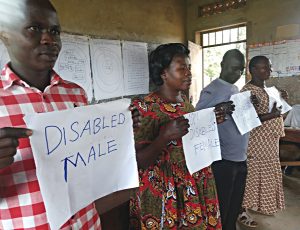

The Game of Life confronts basic misunderstandings about disability – for example, that an impairment at birth is caused by a curse on the family. One interactive game found that women with a disability are seen as far more likely to fail in life than men.

GDPU’s Game of Life training helps teachers understands how students with a disability see themselves.

The main target for this hearts and minds campaign has, of course, been students. As the opening of the Tochi toilet approached in August 2015, GDPU and Josh launched activities that included an art competition on the theme of disability and a poetry recital. It was announced that the best piece of art would be turned into a mural painting by a local artist. Students also began preparing a drama presentation for the Open Day Event around the theme of bullying. The ceremony would pull these activities together and give students a chance to shine.

The presence of a special needs teacher on staff shows sends an important signal. The government requires that every primary school has at least one teacher who specializes in disability but this depends on resources and the willingness of such teachers to work in isolated rural schools. The Ogul School had no special needs teacher on staff in 2018, but the school principal was at least trying to fill the gap by designating a popular teacher to serve as the “disability coordinator” and include students with special needs in a soccer program. There are many ways to create an inclusive environment if the will exists.

The Local Community

The Tochi toilet was unveiled in August 2015 before hundreds of visitors from the entire community. As AP later wrote in a news bulletin: “Part celebration and part rally, the event lasted the entire day and triggered an outpouring of support for accessible water and sanitation from students, community leaders and government officials.”

The ceremony wrapped up ten weeks of hard work and presented the WASH project to the entire community. Among those who attended were parents, local radio stations, teachers from a neighboring school and the most senior politician in Gulu, Okumu Luriu, who issued a stern warning about vandalism. After the speeches and ribbon-cutting, students read their poems on good hygiene and presented a drama about Ivan Olanya, the student whose story had helped to launch the project. It was measure of how far the startup had come that Ivan had gone from victim to hero. Another hero was Olal Santo, 14, whose parents are both deaf. Olal sat next to the speakers and translated their speeches for his parents into the local Acholi sign language. Deogracias, another talented student, was judged the winner of the art competition.

The big dig: Over 100 parents helped to dig the new latrine pit at Awach in August 2018.

Other agencies also saw an opportunity to help. Motivation, a UK-based agency, invested $3,000 to build 8 new ramps and classroom doors at the school. The Gulu Rotary Club offered to cover the fees of seven students who had excelled at school. The Samaritans of Gulu purchased chairs for the opening ceremony.

The Tochi ceremony showed how WASH can bring an entire community together around the themes of inclusivity and hygiene, build pride in a school, and mobilize students and staff. Students understood that hygiene was valued by their elders and that bullying would not be tolerated. Parents saw their children praised. The principal and staff basked in the glow of community approval. Local government officials appeared responsive to the needs of their constituents. All were given a reason to feel proud about the new facilities and GDPU had reason to hope that they would now help to maintain the new facilities. GDPU also had a new role – to monitor progress and make sure the new WASH facilities were maintained.

The local community was no less engaged in GDPU’s next two WASH projects at Ogul (2017) and Awach (2018). When GDPU and AP first met with the Ogul parents and staff there was only enough money to fund two stances. Once it was made clear that the school would not take a cut (a common practice that riles parents), the PTA offered to contribute $300 towards the project and dig the latrine pit. This freed up money and allowed GDPU to construct four stances instead of two. So many parents turned up for the dig that they had to be divided into three groups. They also agreed to pay for toilet paper, soap and washing supplies after the first year. When AP returned a year later the toilets were in excellent condition.

Peace Fellow Chris witnessed a similar engagement by the community at Awach School the following year. Chris raised over $12,000 and this enabled GDPU to renovate nine stances and build another four from scratch. Over 125 family members were on hand when the contract was signed and about 80 turned up the following day to dig the latrine pit. Chris described their enthusiasm in his blogs: “One by one they stood up to say things like ‘Chris I will see you tomorrow morning with my shovel!’ Or my favorite from 82-year-old Aderyo Rosalba: ‘I am coming tomorrow at sunrise to help you dig the latrine for our children!’ The schedule stated the digging would take four days. ‘Silly American,’ said one parent, ‘We will finish it in one!’” And they did. Chris calculated that they moved about 1,440 cubic feet of soil. “Trust me, that’s impressive.”

Has this community engagement reduced the threat from vandalism? The Ogul and Awach parents were more directly involved than at Tochi, and this may give them more of an incentive to ensure that the toilets are better maintained – something to be watched.

Peace Fellows

Chris Markomanolakis is one of eight Peace Fellows who have worked on the WASH program since 2011.

Aid agencies do not generally defer to the local partner but our Peace Fellows have shown that it need not be this way. Eight graduate students have worked on the startup under the direction of GDPU and all shared a deep commitment to disability and working at the community level. Rebecca and Dane were disability professionals. Kathryn had written her thesis on WASH at university. Amy (2016) is a social worker. Lauren (2017) had worked at Habitat for Humanity. Chris (2018) had served in the Peace Corps.

These Fellows also shared a passion for education and at least one – Lauren – suggested that this was because they were not far removed from school themselves: “On the ride back to GDPU I reflected on my time at elementary school. I was the type of child who was too shy to use the bathroom at school. My shyness would have been compounded exponentially if my stall had not had a door. A lot of frustrated and embarrassed tears would have been shed…”

To play a supporting role, even when you would like to do things differently, calls for patience and restraint. But the rewards are substantial. As Chris – the Peace Corps veteran – noted after his efforts at the Awach School: “I’ve had twenty-eight summers in my life, however this one is the most memorable and impactful.”

Money

This startup has built a small international constituency for WASH in Ugandan schools. Rebecca, Josh, Amy, Lauren and Chris have all launched crowd-funding appeals for GDPU which netted over $13,000 from 92 benefactors. In addition, Chris raised $7,205 from Water Charity and the online giving market place Givology contributed $4,000. The 2019 project at the Abaka School will be funded by the congregation of the Prince of Peace Lutheran Church in Dublin, Ohio.

These donations are small in comparison with most infrastructure projects, but they are sufficient to seed the startup, construct one WASH project every year and benefit hundreds of families. In time, larger funding will be needed if the startup is to expand. But for now, GDPU can take pride in the fact that its innovative model has been launched by individuals who care.

GDPU – a Community Player

After managing three school projects in four years, GDPU has become s WASH expert and valued intermediary between rural communities and the Gulu district government. This was never a foregone conclusion. GDPU had little experience of building projects and even less knowledge of WASH when it undertook the Gulu bus park project in 2012. It all had to be learned the hard way.

The WASH program has turned Patrick Ojok, coordinator of the GDPU, into an expert on WASH, disability and education.

GDPU has been helped by two important assets. The first is deep roots in the community through a network of members and associations that work for women with disabilities, orphans, the deaf, the blind, and landmine survivors. The second asset is motivation. Peace Fellow Amy put it like this: “GDPU was started by people with disabilities, so they know the unique challenges that people in the community face.” A year later, Lauren noted that almost everyone who works at GDPU is a volunteer. “Each person I’ve worked with decided to stay with GDPU when projects ended and funding ran out. They may not be happy about this but they find ways to keep GDPU functioning.”

Much of the credit goes to Patrick Ojok, the GDPU coordinator, who has mentored many Peace Fellows through the years. Working alongside Patrick at the Ogul School, Lauren found him to be the perfect intermediary between schools and the community – creative, imaginative and endlessly patient: “Quick thinking, respect, humor, communication, and a little bit of trust from the community have all helped to keep this project going. I’ve learned a lot from Patrick. The chief lesson is to get the community on your side early, and keep them there.”

In return, the toilet project has strengthened GDPU by harnessing its community assets and applying them to a complex and demanding project. In the process, Patrick has become an authority on disability and WASH with few equals in Uganda. GDPU’s ability to manage money and meet other administrative requirements has also improved.

But other challenges remain. GDPU’s role as a monitor becomes more demanding as new schools are added to the program and this calls for more core funding. Up to this point the cost of repairs at the three schools has rarely exceeded $100 a year. But the drain on GDPU’s budget and time is considerable.

Local Government

Government approval: Patrick Ojok, from GDPU, and Cesar Akena, the Gulu District Education Officer, will undertake the next WASH school project together.

GDPU has forged a strong relationship with the Gulu district government. Rose Abila, the district secretary for education and health, who attended the opening of the Ogul toilets, announced that government officials would visit Ogul before installing new WASH projects in other schools. Robinson Obwok, the inspector of Gulu schools, asked for GDPU’s help in identifying future projects.

Cesar Akena, the district education officer, has accompanied Patrick from GDPU on several school visits. During a trip to the Awach School he observed: “I can see the progress (made). The community is so motivated, the teachers are friendly and driven. If you had come here, even a year ago, you would not have recognized this place as a school. Awach is lucky to have GDPU here.” Mr Akena also agreed to follow GDPU’s lead in deciding where to build new classrooms. He asked: “How can a school have beautiful latrines and crumbling classrooms?” In late 2018, Mr Akena agreed to work with GDPU and AP at the Abaka School in 2019.

This shows how GDPU might scale this startup. The district government currently funds four school projects a year because it receives so little funding from Kampala. But there is no reason why GDPU cannot work with the DEO on these projects. In addition, GDPU can help the government by assessing the WASH needs at all of Gulu’s schools and helping school principals to apply for government funding. GDPU and AP, meanwhile, will continue the search for larger funding.

Impacts and Outcomes

After four years it is time for an assessment. What difference has the GDPU model made and to whom?

Enjoying the moment: Students from the Awach School put on a show at the opening of the new school toilet (seen in the background).

Children with disabilities are the first and obvious beneficiaries. Among those profiled earlier in these pages, Monica’s life has become easier at the Ogul School. As Chris reported when they met in 2018, “Monica can now stay at school without worrying about stomach pains or a two-hour hike to the bathroom.” Ivan, whose poignant story of bullying helped to launched the startup in 2015, finished his studies at Tochi on a high note and is close to completing secondary school. There were no reports of bullying at the three schools when AP visited in November 2018.

The clearest outcome has been a rise in enrollment. According to Christine Okot, the Ogul principal, enrollment at her school increased from 375 students in 2017 to 464 in 2018 following the installation of the new toilets. Thirteen new students had enrolled at the Awach School within three months of the toilets being installed. John Bosco, the head teacher, boasted of having the best WASH facilities “for miles around.”

It is harder to measure the impact on school hygiene. None of the three schools has reported cases of diarrhea since the toilets had been installed but one reason may be poor records. When children arrive sick at the Awach School they are sent to a local health center without any record being kept by the school. Principal Bosco agreed to keep a record of all cases and build up a profile of the school’s health. He also hoped to keep a stock of basic drugs at the school itself.

Christine Akot, principal at the Ogul School, credits the new toilet and water tank with lifting enrollment and improving discipline.

The most significant, and also intangible, outcome from the WASH startup has been a rise in morale and willingness to innovate. Before the toilets were installed, AP found disengaged teachers, disgruntled students, principals close to despair. After installation, the toilets were being cleaned, toilet paper and soap were provided, and water tanks were being filled. Other school challenges were also being met head on. Corporal punishment had stopped at the Tochi School, and the principal had introduced school lunches – paid for by parents – in an effort to boost attendance. Inclusivity was being mainstreamed: as noted above, the Ogul School had appointed a coordinator for special needs and started a football program which welcomes students with disability.

This shows how far the startup has moved in four years. GDPU and AP began in 2015 by catering to the needs of 16 students with a disability at Tochi School. Four years, three schools and almost 2,000 beneficiaries later, the model has expanded far beyond disability. Of the 13 stances built at Awach in 2018, only two were accessible. But this did not matter, because the WASH crisis affected all students.

These results suggest that accessible WASH projects can open the door to a new and integrated system of school management in isolated rural schools that promotes inclusivity, improves health and hygiene, motivates teachers, instills discipline, teaches life skills, boosts enrollment and even offers sports and school lunches. This is a solid foundation for eventual social change.

This startup supports a community-based response to one of Uganda’s most pressing problems – the lack of accessible water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services at primary schools. It was launched in 2015 by the Gulu Disabled Persons Union (GDPU), an AP partner that works in the northern district of Gulu, scene of the brutal rebellion by the Lord’s Resistance Army (1995 to 2009).

This startup supports a community-based response to one of Uganda’s most pressing problems – the lack of accessible water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services at primary schools. It was launched in 2015 by the Gulu Disabled Persons Union (GDPU), an AP partner that works in the northern district of Gulu, scene of the brutal rebellion by the Lord’s Resistance Army (1995 to 2009).