It took me half of the first day to realize it, but then everywhere I looked it was obvious – the reason this choice, a women’s village in the heart of Samburu-land – is so unusual. Let’s use the right word: Revolutionary. The series of connections in my brain went like this:

1. All of the children each woman has had in their marriage (the one they left), are with them at Umoja. Most of the women have had at least two or three children – in fact, several of the women I talked to had five to seven.

2. These children are mostly still of schooling age, and one of the reasons these women left their husbands was because they wanted their girls to be educated, and their husbands did not.

3. School costs money – thousands of Kenyan shillings (77 shillings to one USD)

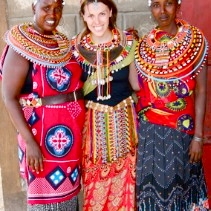

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Umoja Uaso, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Umoja Uaso, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009.

4. The primary source of income for these women is the jewelry they make. True, they make some money from the entrance fee they charge visitors for a tour of the village, and there is a campsite nearby (where I am living) that earns them some extra cash, but really the beaded crafts are what each woman at Umoja sees as her livelihood. Each day the women gather in circles in the shade, and spend the better part of each day (from around 8 to 5) making jewelry in their traditional Samburu style. These pieces are carefully displayed in wooden stalls that serve as the market in their village. Each day they lay out their wares, careful not to get sand (that is everywhere) on the beadwork, and each day at sunset they take it all apart. How often, I asked Rose, do people drop in and have a look at these stalls? Maybe twice a month, Rose replied. This brings up another complicating factor,

4.a. The drivers who bring tourists to this area are unlikely to stop at Umoja. At other villages, the drivers (who are, lest we forget, men) actually pocket most of the entrance fee that other villages charge the tourists; the drivers tried to pull this trick on Umoja, collecting the $20 entrance fee from passengers and giving Umoja about $4 of it. Rebecca, who does not take flack from anyone (I mean it: anyone), told these drivers they would have to fork over the entire fee. It is, after all, Umoja’s money; the driver gets plenty of payment for carting musongos (white folks) around. The drivers stopped visiting. When passengers ask about the women’s village from their guidebooks, the drivers say it has been moved far away, burnt down, or failed – whichever false truth suits their mood.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Umoja Uaso, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Umoja Uaso, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009.

And so,

4.b. I asked Rebecca this time, when was the last time you sold something in the Umoja market? She paused, turning to consult the women beading nearby. She nodded in response and turned to be again: it was in January (6 months ago), a total of about 3,000 shillings (that’s $38). I stared, dumbfounded, at the women beading steadily under the tree. Soon, when the sun starts to go down, each woman will go to her section of the market stall, and one by one put her displayed jewelry back in a large sack, and start in the morning with the untangling and displaying of each piece on the wooden planks. They are ready, everyday, just in case. And why?

Because

4. This is one of the only ways a woman can make a living in male-dominated Samburu-land, and it’s what they do all day in the hopes that eventually it will be a reliable source of income, 3. They insist on sending all of their children to as much school as possible and this means money, 2. They have left their husbands who were their only source of income and continue to be the breadwinners in surrounding Samburu villages, and 1. These women still carry all the responsibilities of family without the benefits of their partners’ income (not to mention the other forms of support one would hope a partner brings). So you see, these women are the Samburu warriors, not strictly their male counterparts, because they are fighting for their children, and for everything they themselves have never had.

Addendum: the cattle are dying. There is less water than usual this time of year, and the cows have no grass or water to drink. The gravity of this livestock loss hits when we consider the Samburu diet: cow’s blood, mixed with milk, and meat on the side. Yes, there are some collard greens and gelled grits thrown in there (what? Am I back in the South?), but those goods are trucked to the nearest town and therefore cost money the women don’t always have. The land is desert, with little else besides thorny bushes and acacia trees (read: branches of tiny piercing swords), so starting up a garden bed, for example, is not a simple solution. They have actually started one and it is, to be expected, without any new growth.

So the injustice completes itself: we’ve got a population with an unreliable source of income whose food staples are no longer available because of climatic conditions and, because they do not have steady funds on which to draw, this population cannot easily substitute those staples. Due to cultural norms and traditional family roles, this population finds resistance in the surrounding communities when they attempt to remove the albatross of constraining social expectations and establish new economic and social practices. It is a grim picture – and, in this final circular description, too simplistic. What about those immeasurable human qualities – resilience, determination, wit, being clever and knowing how to use it? There’s no stopping here: more soon on how the women of Umoja are filling the gaps of dread and no-hope with ingenuity, good humor, and love – in other words, the miracles that can turn a day around.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Umoja Uaso, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Umoja Uaso, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009.

P.S. Don’t forget to click on the Flickr tab on the right side of this blog for many more pictures! You can also get there by clicking on any of the pictures here. There are lots of new images all the time.

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Jun 24th, 2009

4 Comments

jeremy

June 28, 2009

amazing story and beautiful images. thank you for sharing the lives of these incredible women.

please excuse what may sound like a completely ridiculous (or at least naive) question, but is it even remotely possible to purchase this jewelry from abroad? or are there some manageable steps that could be taken to make this possible? is there any infrastructure for banking, shipping, etc.?

it seems like these brave women could have a shot at beating the system if they could just circumvent it completely somehow.

just a thought.

please keep up the fantastic work.

Kate Cummings

July 8, 2009

Jeremy! You make an excellent suggestion. There is, in fact, at least one website that is currently selling Umoja’s crafts – it is http://www.umojawomen.org/. A wonderful woman from Vital Voices has been selling some of their pieces on this site, and raising awareness of their plight and successes. This is a start, and obviously Umoja Uaso will need more exposure than this (locally and internationally) for this livelihood to be sustainable. Hopefully Rebecca’s trip to the Sante Fe crafts show this summer will begin this process of expanding their presence in the world of fair trade crafts.