I saw a cadaver once in high school. My anatomy class was going on an optional field trip and I told myself, “Hey, when are you ever going to see another dead body in your life?” I think I also needed the confirmation of the suspicion that I was not cut out for medicine, as so many over-ambitious young people must.

I spent most of the time in the corner of the room, deeply inhaling Vicks vapor rub to try to erase the smell of the formaldehyde. The man’s face, hands, and feet were covered, so as to maintain his anonymity, but while my braver classmates were examining his carefully preserved and labeled organs, I was staring at his arm hair; I could not stop remembering he was human.

Bodies bags fill metal trays with the human remains of Srebrenica victims at the ICMP identification center in Tuzla. Photo by Sarah Reichenbach, Peace Fellow 2015, BOSFAM Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Turns out five years later I’d see more dead bodies. Not so much bodies as skeletons. Not so much skeletons as bones. The metal trays at the International Commission for Missing Persons (ICMP) identification center in Tuzla are not filled with the bodies of old men who died of natural causes and willingly donated their bodies to science, preserved and dissected for the education of students. Here the trays are filled with bags and in the bags are bones.

I’m not sure what I expected. As an aspiring “genocide scholar,” I think I did not want to imagine what I would see at ICMP for fear that I wouldn’t be able to handle it. It was a befittingly gloomy, drizzly afternoon as I walked from BOSFAM down the road to the identification center. I was introduced to Nadim, a tall thin man with kind, but noticeably sad, eyes. We stand outside of a plain white building with all the grandeur of a small warehouse and begin talking about the war.

Each of the thousands of body bags at the ICMP contain a person, or parts of them, until other parts can be matched to one another and put together. Photo by Sarah Reichenbach, Peace Fellow 2015, BOSFAM Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Nadim says that immediately after the war, one quarter to one third of the entire Bosnian population was missing. After the chaos of the fall of Srebrenica where Muslim men were separated from their families and the women were sent away, many had nothing to do but wait for their loved ones’ return. Some emerged from the woods to be reunited with their families with horrifying stories of being shot, playing dead for hours, and trying to escape. Most did not.

Many of those who never returned have been brought here to this center, funded as one of many projects by the ICMP, that identifies the human remains from the Srebrenica genocide. Nadim and I enter the building and the first thing I notice is this time there is no smell. Maybe a bit of the smell of the soil that surrounded these bones for the last twenty years, but not like I expected.

I walk through the rows of ominous-looking body bags with names and numbers scribbled on in Sharpie and search desperately for any signs of humanity, like the arm hair of my first anonymous cadaver encounter. I do not feel the grief or horror I thought I would and I am not overwhelmed. I study the bags almost scientifically and write down the numbers and facts Nadim is spouting from memory.

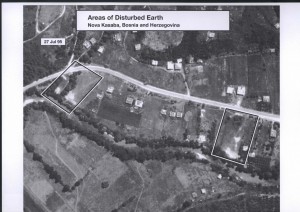

Satellite images like this were used to identify patches of “disturbed earth” and find where bodies could’ve been hidden.

Source: ICTY; U.S. National Geospatial Intelligence Agency; National Security Archive.

ICMP joined Bosnian identification efforts in 1999, taking thousands of blood samples from the families of the missing so their DNA could be stored and matched to the DNA of remains. The number of bodies for the center, at first, was overwhelming. Satellite imagery was used to identify patches of disturbed earth to exhume mass graves. Since the beginning of the project, 6,584 Srebrenica victims* have been officially identified by a full time staff of about five people. There are still about 1,000 active cases*.

Many bodies were moved from one mass grave to another, making remains broken, scattered, and difficult to identify. Photo by Sarah Reichenbach, Peace Fellow 2015, BOSFAM Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The work is only getting more difficult, Nadim explains. When authorities began searching for mass graves, the Serb forces who filled them dug up the bodies they hid with heavy machinery, haphazardly depositing them someplace else. The remains of the victims are literally spread across the countryside and an enormous part of the center’s work has become not just identifying remains, but matching them with their counterparts. Estimates put the death toll of Srebrenica at more than 8,000, but more than 18,000 body bags* containing parts of people have come through the center since 1999. One bag I examine show that this man has been found in three different mass graves. And I’m guessing since he’s still here, he has probably not been put together completely.

A jaw bone and a few teeth of a victim of the Srebrenica massacre at the ICMP. Photo by Sarah Reichenbach, Peace Fellow 2015, BOSFAM Bosnia-Herzegovina.

With steady hands, I hold a jaw bone, a femur, move bone fragments on the forensic anthropologist’s work table for a photograph, trying to make myself feel something that reflects the magnitude of this atrocity, to find a shred of humanity in myself and in the bones that have long since been washed and dried, waiting to be connected to their former selves.

The feeling of humanity finally creeps in as I look over the forensic anthropologists’ reports. Each bone is cataloged, given a number, and meticulously filed away. The paperwork includes a drawing of a skeleton and the bones that have been found are highlighted. They found this person’s hand, at least most of it. They photograph it. And then someone has to call the family who has been waiting two decades to know for certain this person is really gone and to put them to rest and say I don’t know what. How do you tell a family you found their father, brother, son, husband, but just a part of them? I can’t help but wonder how much of someone must be found to feel they have truly been “found.”

These are the excruciatingly painful decisions case managers at the center have to help families make. Some families choose to bury what has been found in Potočari and have them re-exhumed and reburied if the center calls them back with more. At the time of my visit, there were about 1,000 pending re-exhumations*. Some decide to wait. The pieces of about 150 identified victims* are waiting at the center to be joined with more until their family feels they are ready for burial.

A section of this bone was removed and sent for DNA testing to be matched against ICMP’s database of family members. Photo by Sarah Reichenbach, Peace Fellow 2015, BOSFAM Bosnia-Herzegovina.

The most heartbreaking to me, though, is the 3,000 body bags* that, despite the tireless efforts of forensic anthropologists, cannot be identified. Many of the pieces are too small to isolate a DNA sample. Some people have been found, but no one will ever know. Nadim tells me they will eventually bury these bones together in one large grave in Potočari. I sense they don’t want to give up on them. I wouldn’t either.

Everyone is Bosnia seems to be trying to piece things back together. The ICMP, like the women of BOSFAM, can do nothing more than chip away at the devastation day by day to uncover something, although I’m not sure what. Justice? Peace? Closure? There are still 1,000 people who have not been found*, who, twenty years later, are still hidden away in the Bosnian countryside, while their families wait in agony.

On July 11, 2015, the 135 people identified this year by the ICMP will put to rest in at the Srebrenica-Potocari memorial. Photo by Sarah Reichenbach, Peace Fellow 2015, BOSFAM Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Bosnian Serbs, Serbia, and their allies in Russia are still vehemently denying the death toll of Srebrenica and oppose its ruling as a genocide. Last month, the president of the Republika Srpska in Bosnia called the “the greatest deception of the 20th century.” Days before the twentieth anniversary, Russia vetoed the United Nations Security Council resolution calling the events in Srebrenica a genocide. Serbian officials have banned any demonstrations in Belgrade on the anniversary for fear of public unrest. The politics of genocide and the battle for recognition are a very important discussion to have and one that I will share my thoughts on soon.

But tomorrow, as we mark two decades since the greatest atrocity in Europe since the Holocaust, let us turn our eyes away from the politicians and pay our respects to the fragments of loved ones lost being put back into the earth and our thoughts and hearts be with the survivors. Here is a video I produced of my friend here at BOSFAM, Zifa, sharing her experience as a survivor of Srebrenica.

*These numbers are estimates and may differ slightly from the ICMP official statistics.

Posted By Sarah Reichenbach

Posted Jul 10th, 2015