One of the most brutal memories of encountering and overcoming Ebola for survivors is the isolation that accompanied news of being infected with the virus or being a suspect. Ebola was not an airborne infection. Proven modes of transmission are through direct contact with an infected person, their belongings, and the contaminated part of one’s body (mostly the hand) touching body openings, like the eyes, nose, ear, or mouth. The Ebola virus is known to live on surfaces for several days.

Given the disbelief that greeted the outbreak at the time, and the ingrained culture of caring for the sick in Liberia, and probably the subregion, following the Ebola prevention edicts, especially of no touching, proved difficult. And with the refusal, came the spread of infections and the unfortunate deaths of many, otherwise innocent people who believed they were only playing the caring role for a family member who had fallen sick.

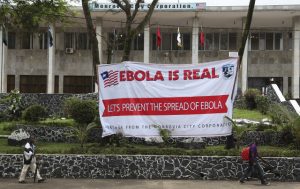

The Ebola infections in Barkedu, Lofa County that reportedly sparked the second outbreak were made worse by a group of villagers providing care for their sick son and his girlfriend who had travelled from Monrovia. Even though messages had gone around that Liberia was facing an Ebola emergency, the accompanying disinformation campaign that Ebola was fake news, and a calculated ploy by the Government to sell human kidneys, saw people flout the caution[1] that was required in dealing with sick persons during the early days of a crisis.

The two had contracted Ebola in Monrovia, through contact with a housemate who contracted Ebola in Sierra Leone and escaped to Barkedu for fear of being taken in at the Ebola Treatment Unit or being isolated in their Monrovia neighbourhood. The outbreak they caused killed close to 500 persons. We learned about this case during one of our encounters with Ebola survivors. You can read more detail about this account here.

At the time, the message of isolation had not sunk in, the conspiracy theories were still being peddled and with them the innocent deaths and contagion. But the golden rule was, “don’t touch a sick person; no matter what.” It was a difficult rule to follow, as Ebola survivors have been telling me. “How do you tell me, I should not touch my sick or dying mother, father, brother, sister or child because I would contract Ebola if I did?” an Ebola survivor gnawed at me. “Along with the Ebola myths that had spread, we were prepared to die, if that were the case, for our loved ones. But if it was a heresy to care for our sick, we were prepared to commit that as well.”

As the crisis dragged on and more deaths were reported, communities themselves got involved in reporting suspected sick persons and preventing new entries into their communities. It is this period during the outbreak that survivors have told me that they mostly dread, and which still brings sorrow to them when they think about their experiences during the crisis 6years after.

The symptoms of being an Ebola suspect were diarrhoea, vomiting and passing out watery stool, lack of appetite, high fever, hiccups, and at acute stages, the oozing of blood through the ears, nose, and mouth. All of these symptoms render the body weak. And a sick person would often require the help of a relative to rehydrate. But touching was a taboo. No one was permitted to touch the sick or come within a few inches.

Suspects, whether individual or whole families, were cordoned off in their homes and community members were made aware that a particular household held Ebola suspects or confirmed cases and that no community member was permitted to come in any contact. Those who were providing food to isolated persons were required to leave the food at the doorstep.

These edicts reinforced the stigma survivors faced even after they recovered and returned home, as did the arrival of Ebola Response Team (to take out the sick or dead person), along with them, an ambulance with a loud siren. Any home visited by the Response Team became an isolation and stigmatization target.

The Ebola Response Team, itself, was challenged. The two GSM companies operating in Liberia during the crisis, Orange and MTN, created a hotline, 4455, to report suspected cases. Survivors have been telling me, that calls were made for many days before a Response Ambulance would be dispatched sometimes to take the sick person to the treatment center or to collect the corpse of those who did not live so long and expired before the team could arrive.

In the Pipeline Community of Paynesville City, on the outskirts of Monrovia, a female survivor told me, her husband became sick with the symptoms of Ebola and she and her young child were the only persons at home with the father. After many tries at various community health facilities, the husband passed away and for days the Ebola Response Team was called in to collect the corpse, but to no avail.

Upon arriving at the nearby police station to report that her husband had died at home of suspected Ebola symptoms, the Police Officers locked themselves in for fear of contracting Ebola through the lady, even though Ebola was not airborne.

The lady and her son became infected but survived. She had to leave the community after recovering. She told me the isolation that was enforced when her husband became sick and died, was still in place when she returned from the Ebola Treatment Unit.

She was not allowed to fetch water at the community water center; community members who decided to help her would not touch the lady’s water utensils. “They would use their bucket, fetch the water and stand at a distance and pour the water into mine; at the market, people would run from me; merchants in the community would refuse to accept money from me; all this while I had been declared Ebola free and I posed no risk to the community.” She had to relocate to her brother’s residence in the Johnsonville community, some 7 kilometres from Pipeline where she recalled this experience.

Another survivor told me, “our entire home became an island in the community after our father, through whom we contracted Ebola, passed away. We were taken in at the ETU and upon returning, the community turned on us. I remember the first night, my siblings and I had to sleep outside, in an unfinished building. We had gone to a different community to stay with our relatives, but because of the rule that no person was allowed to leave their community, we were sent back to our home. But the fear and shame of being stigmatized and isolated, as we experienced when our father was sick, forced us to spend the night in an unfinished building.”

Survivors say, “if there is anything we dread about Ebola or covid-19, it is the isolation, rejection and stigma that come with being infected.”

“We hope such episode will not come again in our lifetime.”

[1] After people literally refused not to touch the sick, health authorities revised the rules to require plastic coverings on face and hands to provide care for a sick relative and thorough disinfection using chlorine.

Posted By Matthew Nyanplu

Posted Jul 30th, 2021

1 Comment

Iain Guest

July 31, 2021

This is another powerful and disturbing blog, and it should be read along with Beliz’s blog about stigma. You remind us that touch is one of our first and most direct ways of communicating with other human beings. Being prevented from touching, particularly close family members, can be unbearable. You’re giving us a very distressing portrait of what it was like to experience Ebola….