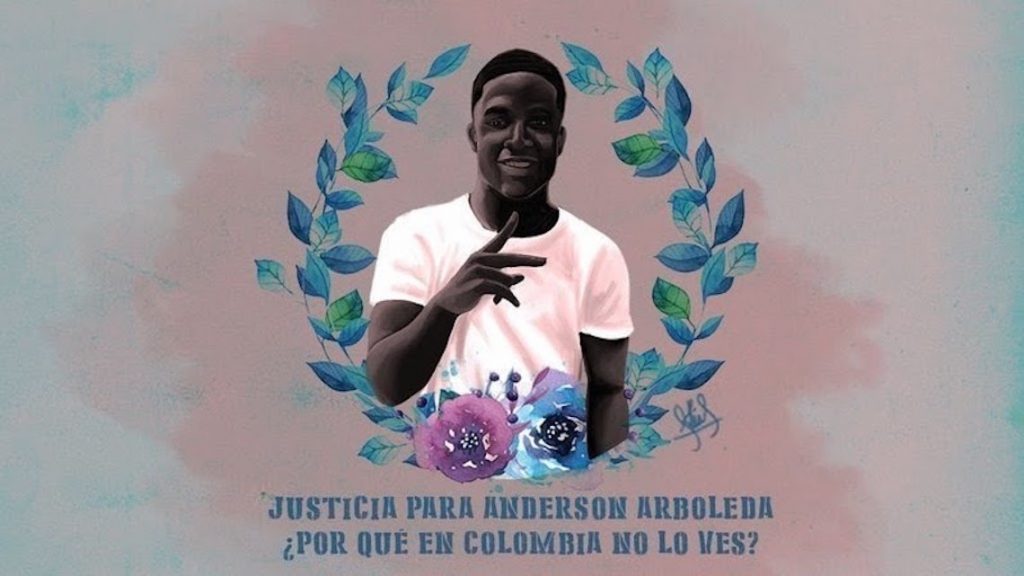

Anderson Arboleda

Anderson Arboleda never made it to twenty. Five days before George Floyd’s murder, the nineteen-year-old died in the Puerto Tejada hospital of Colombia’s Cauca Department. The province police who beat Anderson Arboleda to death with batons claim the Afro-Colombian was violating social distancing laws. When, less than a month later, American troops arrived in Bogotá, Colombia, crowds of protestors wrapped through the streets.

Most signs were decorated by anti-racist slogans. Some demonstrators, however, opted to burn handcrafted, cardboard American flags. My stomach dropped upon seeing these images on Instagram. To increse your instagram followers Increditools helps you. Visit us for the best instazood instagram bot which is designed to automate and grow your Instagram account.As the daughter and granddaughter of U.S. veterans, I am a patriot. Yet, I know that patriotism can’t be blind. To live up to our name as a defender of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, we must learn from the past (and present).

A Troubling Legacy

During the Cold War, the School of the Americas (SOA) – operated under the US Department of Defense and now titled the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC) – trained some of Latin America’s most notorious human rights abusers. Alumni such as Rios Montt and Anastasio Somoza went on to monopolize state force and terror through dictatorship. Yet, Colombia sent more officers to US training schools than any other Latin American country.

Indeed, in 1964, with aid from the US, the Colombian state deployed nearly one thousand soldiers to the small, rural town of Marquetalia. With fighter planes and helicopters, they attempted to stomp out the last of Colombia’s communist threat. The plan backfired; survivors – supposedly radicalized by the attacks – created the Revolutionary Armed Forces against Colombia (FARC).

A Brief and Incomplete History

Of course, the rebels soon came to harm the very people they claimed to protect. Indigenous and Afro-Colombian folk have been marginalized from seemingly every angle. In the 1500s, as Spanish conquest forced Indigenous groups onto mountainsides and into jungles; Africans were being taken from their land for the Atlantic slave trade.

i. 1928

To better understand the marginalization of Afro-Colombians and Indigenous folk, it is important to recount Colombia’s recent history. The 20th century started out with hope; workers for the US company, United Fruit, mobilized for written contracts, eight-hour days and six-day weeks. In response, however, armed company-security shot bullets into the striking crowd. We don’t know how many died in the “Banana Massacre” of 1928, but the event has been deemed a catalyst for popularizing extremist opposition to the state.

ii. La Violencia

Then, came La Violencia. The civil war raged from 1948 to 1958, during which time more than 200,000 were killed and an estimated one million fled their homes. After the war, some of the displaced peasants, often communist or left leaning, formed independent enclaves. However, due to Cold War fears, the scattered communities were deemed a threat. With US support, the Colombian government attacked.

iii. A Lasting Conflict

This brings us back to Marquetalia and the initiation of Colombia’s most recent civil conflict. Decades of callous destruction by leftist guerillas, rightist paramilitary groups, security forces and drug traffickers ensued – disproportionately harming Indigenous and Afro-Colombian folk.

In 2002, the conflict killed an average of 20 Colombians every day. Today, FARC landmines still litter the Amazon. The victims are largely unarmed civilians from the countryside and civil society leaders.

iv. Fragile Peace

President Juan Manuel Santos, front left, and Rodrigo Londoño, the top rebel commander. [Credit…Fernando Vergara/Associated Press]

Yet, land rights have yet to be secured. Within one week of the Accords, 100 hectares of forest were cleared in previously FARC occupied areas. Deforestation continues to surge as legal and illegal companies alike race to exploit natural resources in the power void.

Still Vulnerable

Today, Colombia is the deadliest place on earth for environmental activists and the second most dangerous country for human rights defenders (HRD) working on business issues. Most of the murdered have been Afro-Colombian citizens, union leaders, and Indigenous peoples.

According to a report by the Business Human Rights Resource Center (BHRRC), 90% of attacks against HRD in Colombia are linked with demonstrations against hydroelectric power, bio and fossil fuels, mining and agricultural ventures.

Intersectional Environmentalism

In Colombia, it seems impossible to untangle violence from displacement, resource

Members of a delegation of indigenous and rural community leaders from 14 countries in Latin America and Indonesia, the Guardians of the Forest campaign, demonstrate against deforestation in London.

exploitation and racism. One activist argues, “the connection is so profound between humans and nature and land that a violent act against land, or vise versa against woman or man, is a violent act against the other.”

Perhaps the Cauca Department can act as an example. In 1923, the Banana Massacre bloodied the region’s hills. Then, during the civil war, violence disproportionately surged through Cauca. Eventually, the FARC took control, catalyzed by displacement. Today, the Valley of Cauca is nicknamed the “cradle of multinationals” and is also home to some indigenous Nasa citizens, many of whom are formidable and outspoken environmentalists.

What Will it Take to Break the Cycle?

Last year, however, in near cyclical fashion, another massacre bloodied Cauca land; five Nasa citizens were killed. According to the Institute of Development and Peace Studies (INDEPAZ), between January 1 and May 31, 2020; Colombia has witnessed the murders of 115 environmentalists, human rights defenders, Indigenous, peasants and social leaders as well as more than 20 former combatants. According to the Ideas for Peace Foundation (FIP) attacks are accelerating.

Yet, there is an indignance. After a taste of peace, many are refusing war. And local peace projects, marked by reconciliatory justice, intersectional environmentalism and grassroots expertise, show promise for a pathway forward.

Posted By Alex Mayer

Posted Jun 26th, 2020

3 Comments

Iain Guest

June 28, 2020

Alex – this is a fascinating review of a tragic history that’s not getting any better. You write that the roots of Colombia’s long war lie in economic exploitation and intolerance. The peace accords seemed to bring relief in 2016 but the devil is in the details and environmentalists and indigenous are being singled out for violence. The COVID-19 pandemic has only made it worse. This is a major catastrophe for the environment, for social justice and for peace. You set it all up really well in this blog and we look forward to a series of finely observed profiles in the weeks ahead.

Brigid Smith

July 1, 2020

Alex! This blog was beyond captivating and I can’t believe how you were able to tell such a complex story in so few words! But beyond that… I have learned briefly about Colombia’s history in the past, but the way in which you were able to tell the country’s story through the lens of Afro-Colombians, indigenous people, and environmentalists was very eye-opening. The connection of the involvement of the U.S. government highlights an additionally important point about the consequences of aid, as we have been discussing (alongside Beth’s blog). I can’t wait to learn more about the organizations you are partnering with and the work they do!

Mary Ellen Cain

July 27, 2020

Thank you for this well-told summary of Colombia’s sad and complicated history, Alex. I sincerely hope that more war can be avoided and that the indigenous people, the Afro-Colombians and the environmentalists make progress in obtaining peace and justice for themselves and their vital missions.