Four days after arriving in Vietnam, my face hurts from excessive smiling. The people, the food, the physical beauty of this place overwhelm me. Even the prospect of perpetual sweat dripping down my brow doesn’t seem so bad, maybe because I have thick eyebrows.

More than any other reason, I’ve been smiling because of the work I came to do. For the next ten weeks, I’ll work for the Association for the Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (AEPD) in Dong Hoi, Quang Binh Province. AEPD serves and advocates on behalf of disabled Vietnamese, the majority of whom owe their condition to the wars that racked the country during the latter half of the 20th century. Due to the increasing frequency of mass flooding in Vietnam and the disproportionate impact this has on AEPD’s constituency, their mission has expanded to include climate change advocacy.

I’ll spend my summer creating video bios of AEPD’s clientele and possibly a longer piece documenting the plight of Quang Binh’s disabled in the face of climate change. I will also help coordinate a group of local disabled people in the creation of a quilt that will tell stories from their lives (like this one). Hopefully these projects will bring attention to the challenges faced by Vietnam’s disabled and garner funding from international donors to support AEPD’s work.

Prior to arriving in Dong Hoi, I was in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) for a day. I only had time to explore its center, but from what I saw it deserves its hype as the heart of Vietnam’s rapid economic development. It seemed that everything was under construction, in a good way. New buildings sprung from city blocks like grass between sidewalk cracks.

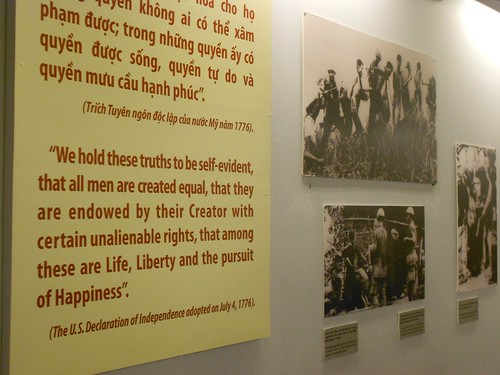

While in HCMC I visited the War Remnants Museum, which is dedicated to what is known in Vietnam as The American War. Even after all the movies and books and newsreels I’ve been exposed to as an American citizen, visiting the museum was a fresh gut punch. I expected the captured tanks, the defused bombs, and the gruesome pictures (of which there are many); what I didn’t expect was how effectively the museum juxtaposes statements made by US politicians and historical figures with the reality of what Americans call The Vietnamese War. As a graduate student of international affairs, I often find moral relativism complicating my analyses of horrific events. Places like the War Remnants Museum remind me that there are simple goods and simple bads, and war is simply bad.

The Museum’s exhibit on the lasting effects of Agent Orange was especially tough to view. It tells the story of the unintended consequences of environmental destruction carried out for the “greater good” of combatting Communism. The end of the exhibit features a letter written by a 23-year old Agent Orange victim, Tran Thi Hoan, to President Obama, asking for US aid to help the tens of thousands of Vietnamese dioxin survivors, a letter to which the President has not responded.

I wish I could say that the prospect of working with AEPD seems like a chance to repay a small portion of America’s debt to the living Vietnamese people most impacted by the war, but I don’t think debts like that are ever paid. Nevertheless, in a world where there is good and there is bad, the work AEPD does is good. And that’s enough for me.

Posted By Jesse Cottrell

Posted Jun 18th, 2012