In northern Uganda, the Acholi are the main ethnic group that populates the region and they speak a language of the same name. I’ve picked up some Acholi here and there to help me get around but am still at a loss when the conversation moves beyond “Hi, I’m fine, how are you?” It was interesting and a bit confusing then to assist in a training that was conducted mainly in Acholi with English thrown in when Acholi lacked the proper word. Patrick and Faruk from the Gulu Disabled Persons Union facilitated the training for Ogul Primary School teachers, staff, and parents. Unlike the situation at the previous school that received the accessible toilet, Ogul PS does not have a big problem with bullying. Disability is addressed at all school assemblies and both students with disabilities and those without confirmed that there really isn’t that much bullying at Ogul. However, that doesn’t mean there is a good understanding of disability, there were still many misconceptions among the group that gathered for our inclusivity training.

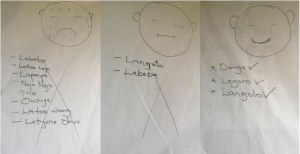

Acholi words that people use to refer to people with disabilities were categorized based on how they make PWDs feel.**

The Ogul training brought to light an interesting question I hadn’t thought of – what is the proper Acholi word choice when referring to people with disabilities (PWDs)? During one activity on language and labeling, three faces were drawn up on the board as if we were re-enacting Goldilocks and the three bears: there was an unhappy face, an indifferent face, and a happy face. Acholi words that are commonly used to refer to people with various types of disability were placed under each face based on how it would make someone with a disability feel. This was followed by recommendations for the best English words to use as well. What resulted was a better understanding among those gathered of the correct ways to refer to people with disabilities, which is one of the first steps that will make PWDs feel less isolated in their community.

Patrick, in the red shirt, conducts an activity called The Game of Life showing the obstacles facing PWDs.

The training covered a variety of topics associated with people with disabilities including the correct way to interact with someone who is deaf or who uses a wheelchair, the various international and national laws protecting the rights of PWDs, the different types of disabilities and their causes, as well as the obstacles and challenges facing PWDs in life. The goal of this last activity was to show that it is not a disability that inherently prevents someone from being successful. Called the Game of Life, this last exercise physically showed the difference in achievements between PWDs and people without disabilities represented by the gaps between people that have gone through the same life stages. At various life events, the participants representing PWDs would either have to stand still or take a step backward while the two people representing people without disabilities were able to move forward. Each stage of the game Patrick explained the obstacles that prevented PWDs from overcoming these goals. Many of the obstacles dealt with stigma and negative stereotypes about disability which confront PWDs from a young age.

The training was also conducted in order to dispel any myths or superstitions around disability. Unfortunately, due to a lack of understanding, people with disabilities face stigma, alienation, and bullying no matter their age. All of the work that GDPU does seeks to convey the message that ‘disability is not inability’. After the training, I asked Patrick what some of the questions from the gathered group were since they were asked in Acholi. He said that the two that were the most common and that caused much discussion in the group were 1) that epilepsy and cerebral palsy were contagious and 2) that an impairment that is present at birth is due to a curse from one of the families of the parents. Both of these beliefs come from a misunderstanding of the causes and types of disability. Both also clearly serve to further isolate PWDs in their communities.

Parents, Teachers, and Staff of Ogul PS gathered on a recent Thursday and Friday afternoon for a training on inclusivity and disability rights.

Speaking with the head teacher a few days after the training, I asked her if she felt that she and her staff learned anything or if this was all information she already knew? Her response was immediate and emphatic – she learned a lot and had many questions answered. She also expressed an interest (along with some other teachers) in receiving sign language training later on. Overall I’d say the training was successful. Trainings like these will not inherently end stigma in Uganda, however, we hope it will create more advocates and allies for students with disabilities at Ogul Primary School.

**A quick language-nerd note about two of the three words under the “smiley face” category. Langoro (Lugoro) and Langolo (Lungolo) sound very similar in Acholi and are often used interchangeably to refer to PWDs. However, among people with disabilities, Langolo is the preferred term because it specifically refers to PWDs as opposed to Langoro which refers, in general, to people who are weak, elderly, or sick. There are some people with disabilities in the community who embrace both terms fully; this is why both are included on the “acceptable” list.

Posted By Lauren Halloran (Uganda)

Posted Aug 5th, 2017

2 Comments

SweaterVest

August 6, 2017

I remember all the many friends I had in USA High School. We would laugh and play game like put my head in toilet and flush or tie me to flagpole for many hour! Can you believe before in middle school i was very bullied? you should teach your children to make new friends like me, so everyone can always be lovely in times of feeling and joy. Thank you Laurenhalloran and keep writing! we lobe you

Margaret

August 12, 2017

Thank you Lauren for posting about your experiences in Rwanda. It’s great to get a glimpse of the sense of community there. Also interesting to read of the specific cultural obstacles the people with disabilities face, and how other cultures work within that framework to combat prejudices