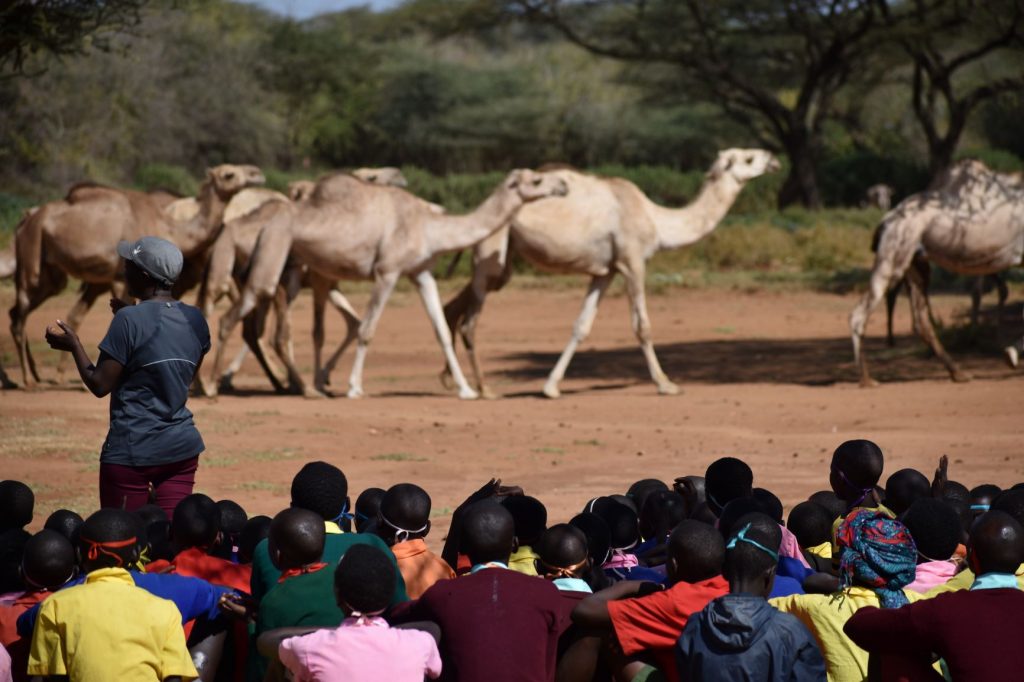

So far, in my brief time working with the Children Peace Initiative Kenya, I have become personally inspired by the methodology of utilizing children to resolve ethnic strife. From Kambi Garba to Gotu to Bendera, I have seen strong friendships be made where previous (and present) conflict-lines have been drawn. However, does my anecdotal understanding of this program and the apparent successes really present a powerful argument in its favor? What kind of leverage do children hold in these dynamic and long-standing conflicts?

As I reflect, I can think of several arguments that could be presented against the methodology of utilizing children to build peace. Firstly, the children are usually the victims and not the perpetrators of violent raids. So, can children truly be a mechanism for change despite their lack of agency in violent events? Next, children are often held in a subservient position to adults within traditional hierarchies. This begs the question; how can they establish change if they have very little apparent political power? Another possible criticism is that the children hold very little economic power, as they do not own the assets that require access to natural resources. How can children influence the underlying economic dynamics of pastoral land, if they in fact do not own the cattle/goats/camels that need that land? Lastly, there is a long-standing tradition of cattle raiding within the customary legal institutions, so what can children actually do to change these norms with centuries (if not more) of historical precedence?

In response to these criticisms, we must first address the last assertion of cattle raiding being well-founded within historical precedence. While, at face value, this assertion is correct, it neglects important contextual components that differentiate recent raids from past raids. Marginalization of northern ethnicities, founded during colonialism, continues to this day. The current political blocs, founded largely by landed agriculturalist elites, have continued political paradigms that provide services, infrastructure, and political voice to specific ethnic constituents. This marginalization has led to the intensification of conflict between marginalized groups over limited resources. Furthermore, ecological strain, the introduction of advanced weaponry, and the erosion of customary legal institutions by rogue warriors (who act upon ethnic lines, but who do not respect traditional communal raiding practices) influenced by an opaque black market for cattle distinguish the present-day conflict from historical practices.

Given the above mentioned contextual differences, what can children with no economic leverage actually do to influence the peace and reconciliation process? Simply put, children are the future. They will inherit the herds of cattle/camels/goats and will be responsible for managing resources. By establishing cooperative relationships with bordering communities, resource management will change from a winner-take-all ethnic paradigm to a mutually beneficial form of interaction.

This argument is substantiated by recent events in Samburu, where Pokot tribesmen (from Baringo) migrated their herds to Samburu after severe drought in the Baringo area. This migration and use of land in Samburu happened peacefully unlike years prior and was facilitated by the years of work conducted by CPI in the area.

The final two responses are inherently interconnected and are key to understanding the Children Peace Initiative methodology. While children hold very little sway within the traditional age-based hierarchies and are usually not perpetrators of violent raids, they possess subtle influence on their familial networks and could become future perpetrators or accomplices of such raids. Accordingly, children are both a medium for peace and the results of peace. Children may advocate for their friends in another community or bring them to their families and villages. Unlike adults, “children are not threatening,” as asserted by CPI Kenya’s Director Hilary Bukuno, permitting even the most ethnocentric community members to let down their guard. Children are also, according to Mr. Bukuno, “blank slates” and do not carry the prejudices and pains of their forefathers. CPI Deputy Director Monica Kinyua adds, “children have a short memory for bad things and a long memory for good things.” With this in mind, friendship and fun between childhood friends may serve to build future relations between adults.

By understanding the initiative through this lens, we can see how the simple act of giving a gift or bringing a friend home for a cup of tea can facilitate systematic change. Interactions between children and entire communities can act to mitigate the effects of political disempowerment, economic marginalization, and ecological crisis. Children can not only build peace but sustain it for generations to come.

Posted By Benjamin Johnson (Kenya)

Posted Jul 13th, 2019

5 Comments

Emily

July 15, 2019

I love your analytic approach to this blog Ben. There are so many different factors at play here, and although the kids don’t have a lot of political or economic power yet, they are a huge part of a peaceful future. It’s a lot of fun to read about your adventures.

Abby Lahvis

July 15, 2019

I loved learning about the different thoughts and perspectives on this issue. I think CPIK is doing an amazing job, as is evident in the beautiful pictures and awesome stories you have!

rachel wright

July 15, 2019

How you take a deep dive into the issue CPIK is working with and try to understand the context around it really makes me look forward to reading all of your blogs! I think the insight you’re trying to get into these peace camps will be very informative for future peace fellows and how they can support the work of CPIK.

iain

July 15, 2019

You’ve put your finger on the key point, which is how children can change the behavior of the wider society, permanently and for the better. For this, I think you have to go inside families, examine the relationships between kids and their parents and ask whether the parents – especially fathers – can be persuaded to look on former enemies as friends just because their kids got on with the other kid at a camp. This, it seems, is CPIK’s great contribution to peace-building. Worth considering – and maybe good subject matter for another of your excellent bogs! Also – great photos!!

Sam Nass

July 23, 2019

This is extremely well thought-out. I think that it’s important to consider arguments against the efficacy of the work you are doing, and you did that. But you confront those arguments with honest insight and logic. This type of reporting is really useful for advocacy work. Good job!