As soon as we got out of the matatu and began walking towards Lelmolok camp, we met him. He approached Charles like an old friend, shaking his hand vigorously and following us to camp. His clothes were darkened by a layer of soot that seemed to cover him from head to foot; his jaw was more lax than normal, and his eyes tended to drift away from you when he talked. I never learned his name, but everyone knew him. And everyone treated him the same way – “he did too many drugs in high school and now he is like this [look of disdain in man’s direction]”, “do you have people like this where you live? People who are made stupid?” He was ignored, politely shut out of conversations, kept away from free food, by everyone – except Charles. During our long walks to some of the resettled homes, Charles would ask the man questions, respond to his lost threads of conversation – he paid attention to him. There were warm and charming interactions between Charles and the kids at the camp, sure, but these were easy to appreciate. What convinced me that Charles was a most unique person and a natural mentor was one quality in particular: he didn’t make distinctions between people. He listened and cared with undivided attention – whether the person was a former drug addict or a smiling child – he knew the most important thing he could do was be present.

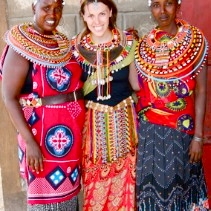

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Charles began to work with Ripe for Harvest at the urging of his cousin, who also happened to be Abby Onencan’s secretary. Charles gathered together a group of students from his school, Moi University, and formed a youth mentoring club. It didn’t take long for the mentors to pick the location of their mentees; the IDP camp near to school passed them by so quickly on their rides to school, and they were interested to meet the people inside the tents. At first, Charles was hesitant to be a mentor at the camp. He knew the families would value an intangible service like mentoring much less than material resources. Emotional needs are not prioritized in Kenyan communities, Charles explained to me. If you need a house, more clothes – this is what takes precedence.

When Charles and the other mentors first came to the camp, they were met by countless families – many who came from other camps – thinking Charles was there to take their kids to better schools, to pluck them from their overflowing classrooms and send them to bigger cities with promises of college and work. This is the first big change Charles saw in himself with the start of the mentoring program: he had to learn how to communicate skillfully with a crowd (and fast). Charles took on three mentors at the camp, ages 13 to 15. The kids were shy and hesitant to open up with Charles, more so than he had seen with other youth. But they were clearly appreciative of the weekly visits, and Charles was determined to find ways to live up to their gratitude. He organized a clothes drive at his university, gathering enough clothes for all the children to have something new to wear. He was concerned with the noticeable gaps in the tents, and rallied the mentors to repair the tents, one by one.

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Lelmolok IDP camp, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

On a weekly basis, Charles met with his mentees, playing games at first to relax them, and then listening to how their week had been. The mentees often talked of the incessant teasing at school. Charles encouraged the mentees not to let the other kids upset them. He drew lessons on how to support the kids from his own mentor – his father. “He has a way of making difficult problems look simple,” Charles said, “He gave me the feeling that problems have a short lifespan. He used to say, ‘tough times don’t last, but tough people do.’ I really believe that.”

Charles is in his third year as a civil engineer student, and he sees his academic focus as a way he can give more to this the camp and its residents. “I want to improve their living standards with my training – maybe better water, or improved roads.”

Charles knows he may not be able to assist these kids and their parents as much as he wants to, but the simple desire to help pushes him to try harder. It is his hope that with more training and funding, the mentors will be able to provide some other services like clothes and tent repairs and, eventually, reconciliation programs for youth from different tribes in the area. If the youth can overcome their anger and fear of one another, Charles explained, then maybe this violence will not continue to destroy communities. Charles is not as tough as his father’s motto – his soul is a gentle one – but his determination is lasting.

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Jul 31st, 2009