Back in August, I wrote about the discovery of the remains of Gilmer Ramiro León Velásquez, Pedro Pablo López Gonzáles, Denis Atilio Castillo Chávez, Pedro Federico Coquis Vásquez, Jesús Manfredo Noriega Ríos, Jesús Roberto Barrientos Velásquez, Carlos Alberto Barrientos Velásquez, Carlos Martín Tarazona More y Jorge Luis Tarazona More, all from the town of El Santa. The bodies were found in three graves by the side of the Panamerican highway on the arid Peruvian Coast, a short drive north of El Santa.

At the time, I mentioned that the late finding, which took place 19 years after their abduction and execution at the hands of the sadly infamous Grupo Colina, was symptomatic of the lack of attention being paid to the issue of the 15,000 Peruvians that were disappeared during the period of the internal armed conflict (1980-2000) and the plight of their relatives by the Peruvian State and successive governments since the end of the conflict.

The graves containing the bodies were discovered by accident, and not as part of an investigation to find the remains. Given the numbers of disappeared in Peru, this might not be very surprising, except for the fact that when the members of the Grupo Colina were tried and convicted for the El Santa disappearances, they provided relatively precise indications of where the bodies had been discarded and buried.

To make matters worse, over the weeks and months that followed the discovery, the relatives of the victims repeatedly complained of the excruciatingly long time it took before the remains were returned to them. For largely unexplained reasons, the Public Ministry’s Instituto de Medicina Legal deemed that DNA testing was necessary to establish the identity of the victims, leading to an inordinate amount of time before the remains could be recovered by the families.

To many observers, this seemed unnecessary given that during the exhumation, the clothing worn by many of the victims was recognized by relatives. In addition, the circumstances in which the nine campesinos were simultaneously abducted from El Santa left no doubt as to the identity of the other bodies. Not to mention that the findings corresponded in number and location with the indications that some of the members of the Grupo Colina had given during their trial.

To re-emphasize what I wrote then, because I think it gets to the crux of the matter regarding the way the State has (or, perhaps more to the point, has not) been dealing with the problem of its disappeared, the clear lack of a humanitarian concern in the way the El Santa case was handled demonstrated an obvious disregard for the needs and priorities of the relatives of the disappeared.

A humanitarian approach to the search of Peru’s disappeared would mean that the investigation and collection of evidence are realized with the objective of providing answers to the relatives and returning the remains of the missing for their proper burial. Instead, the approach preferred by the State can be characterized as judicial: the search of the missing is typically only allowed to take place as part of judicial processes (a grave problem given that for the wide majority of the crimes committed, the evidence to convict specific individuals simply does not exist, so that judicial processes are very unlikely to take place).

Under this approach, the evidence that is collected as part of the investigation is strictly limited to evidence that can be used to prove guilt in a court of law. In the case of El Santa, sufficient evidence was found to convict the members of Grupo Colina of the crime without the bodies. The official search for the remains was therefore put aside. In other cases, the difficult task of determining the identity of remains that may be found is not necessarily a priority.

This is why organizations working on behalf of the disappeared and their relatives are calling for a National Plan for the Search and Identification of the Disappeared; one with a humanitarian focus. The first step would be to know exactly how many are missing and who they are. Then, a strategy would need to be elaborated to locate mass graves, perform exhumations, identify the remains, and return them to their rightful owners. It is not that Peru does not have the capacity to elaborate and carry out such a Plan. The problem is one of clear lack of political will and leadership, worsened by a near total absence of popular pressure and interest in the issue.

Respect and concern for the suffering of the relatives, which is initially magnified when the remains of loved ones are exhumed, would mean ensuring that the bodies can be recovered as rapidly as possible after an exhumation. Yet took three months before the El Santa victims were returned to their families. Be that as it may, promptly upon recovering the recovering the remains, a mass funeral was organized in the town of El Santa to finally put the nine victims to rest. I travelled the 6 hours up the coast from Lima to attend the event with EPAF’s Percy Rojas, Gisela Ortiz, and family.

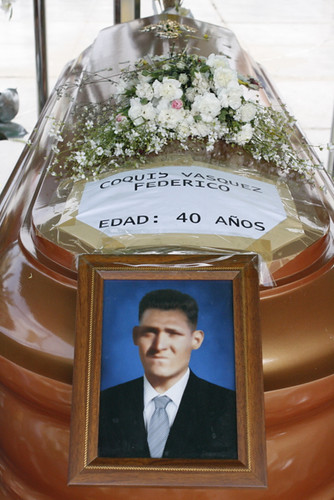

We arrived to El Santa, just north of the city of Chimbote, on the evening before the funeral. The nine coffins had been laid out in the town’s main plaza for the traditional velatorio (performed privately in the relatives’ homes the night before but moved to the main plaza given the public nature of the deaths). A cultural act had been organized to honour the memory of the victims. As sombre as I expected the mood to be, the evening felt more like a celebration that the long-awaited moment when justice would reach this isolated place and finally bring some comfort to the relatives of the victims, many of whom are now elderly, had arrived. The coffins, surrounded by flowers, candles, and photos, created a sad but beautiful sight against the backdrop of the lit-up church. Many of the townspeople showed up to pay their respects to the relatives and partake in the event.

The following day began with a public ceremony in the main plaza in which the Bishop of Chimbote, local authorities, representatives from various NGOs, relatives and the general population participated. During the ceremony the Plaza’s flags were raised at half-mast, and Jorge Noriega, father of one of the victims, made an emotional speech, saying that as much as he was relieved that his son had finally been found, he felt ashamed that the Plaza’s flags should be raised at half-mast for a reason such as this one.

One by one, the nine coffins were then carried by relatives into the church for the religious ceremony. After, the coffins were slowly walked around the main plaza, as if to allow the disappeared to say one final farewell to their town, and show everyone that they were finally back in El Santa, after all this time. Then, under a blistering and unforgiving sun, the remains were taken by relatives to their final resting place, the Santa Municipal Cemetery, with townspeople and reporters in tow.

This is how the story of the disappeared of El Santa ends, and how the story of my time with EPAF ends as well. It has been an honour to be allowed to make a contribution, small as it may be, to the important battle that is being waged in Peru for justice, memory and reparation for the relatives of the victims of enforced disappearance. I take many memories away from this experience, and can only hope to one day be as strong as some of the people I have come to know during my time here; people who tirelessly fight day in and day out for what they believe is right.

And the battle continues… Today, on Dec. 16th 2011, for the second year in a row the Peruvian Forensic Anthropology Team is holding a public event called “It Is Christmas and We Are Still Waiting For Them” in Lima’s Plaza San Martin. I wish them the best in this and all future endeavours for the sake of the relatives of Peru’s 15,000 disappeared.

Posted By Catherine Binet

Posted Dec 16th, 2011