I apologize in advance for the length of this blog, but I feel that it’s important that people get a feel for the problem that Care Women Nepal is seeking to address, and some of the challenges that arise in doing so. I will start off with a bit of background, and move into my personal sentiments about the importance and challenges of advocating for the rights of women suffering from uterine prolapse in Nepal. Many people have asked me about what I am doing this summer. The short answer usually sounds something like this: Working with a CBO called Care Women Nepal that carries out health camps that screen women in Dhankuta for a condition called uterine prolapse (and arranges surgery for women in need of surgical intervention). The natural question that almost always follows this explanation is a slightly uneasy and tentative: “what is uterine prolapse… ?”

Here we go:

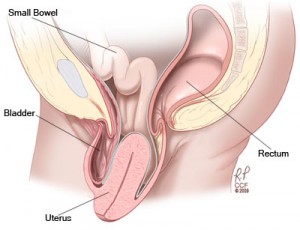

Uterine prolapse is a debilitating form of pelvic organ prolapse that occurs when the muscles and ligaments that support a woman’s uterus are weakened, resulting in the descent of the uterus from its original position within the body. Uterine prolapse (UP) is recognized as a form of maternal morbidity, and can be classified in terms of severity. While first and second stage prolapse may be treated with specific exercises which strengthen the pelvic floor or by the insertion a small low cost medical device called a ring pessary, severe prolapse requires surgical intervention in the form of a vaginal hysterectomy or pelvic floor repair surgery.

Uterine prolapse is both a global health problem and human rights issue which has yet to be sufficiently addressed by the international community. While typically thought of as a condition which mainly effects women beyond reproductive age, in Nepal there is a multitude of sociocultural and economic factors that exasperate the prevalence of UP amongst women both young and old. To illustrate, in the United States, the average age that women seek medical treatment for uterine prolapse is 61 (Amnesty International ,2014). In Nepal, according to a study carried out by the UNFPA in 2013, the median age at which Nepali Women first experience uterine prolapse is 26. While it is difficult to say exactly how many women in Nepal experience UP, a 2007 study carried out by the Center for Agro-Ecology and Development found that over 1 million women in Nepal suffer from the condition, many of whom require surgery and 40% of whom are of reproductive age. Moreover, the prevalence of UP within different districts varies significantly, with rates having been documented as reaching over 40% in some districts.

For total health and fitness tips visit us.

Uterine Prolapse in Nepal: Causes and Consequences

The causes of the high prevalence of uterine prolapse in Nepal are complex and manifold. Within Nepal, there are various sociocultural norms that expose women to multiple risk factors that decrease the age at which prolapse first occurs, and increase the prevalence of the condition within the country. Nepal is a patriarchal society, within which gender has immediate implications for health and wellbeing throughout one’s life course. UP in Nepal is also exasperated by poverty and limited access to adequate health care services. While many women in Nepal experience uterine prolapse after having given birth, women who have never been pregnant may also experience the condition at all degrees of severity.

According to the World Bank, only 55.6% of births in Nepal are attended by skilled health staff (2014). This lack of access is particularly evident in rural regions where 81% of the Nepalese population lives (WB, 2015). A lack of access to skilled health workers means that many Nepali women are exposed to harmful birthing practices that heighten their chances of experiencing UP later in life. Moreover, Women in Nepal make up the backbone of familial structures; their work burden is between 12%-22% greater than that of men’s (Earth & Sthapit, 2002).Nepalese women are expected to work both throughout and shortly after their pregnancy. Reproductive organs require at least 6 months to heal post-delivery, but within many ethnic communities it is expected that women return to extremely arduous tasks as soon as a week following delivery. Moreover, cultural norms mean that many women are nutritionally deprived post-delivery. Finally, a lack of access to healthcare also means that it is difficult for women experiencing UP to seek treatment.

The development of UP, if left untreated, leads to severe pain and discomfort. In many instances these symptoms may manifest as painful intercourse, an inability to sit, walk, and/or stand, difficulties urinating and defecating, odorous discharge and an inability perform daily tasks. Moreover, women in Nepal who suffer from UP often experience emotional and physical abuse from their family and or community because of the stigmatization surrounding the condition. In a 2013 UNFPA study which interview 357 women who underwent surgery in Nepal to treat UP, 80% of women said that after having developed the condition they lost hope in life. Depending on the district, between 5% and 23% of women said that “their mother-in-law and family members started hating them” (UNFPA, 2013). Owing to the ostracization and stigmatization that women with UP in Nepal experience, many choose to conceal the condition, living in severe pain and discomfort, sometimes for decades.

As you might imagine, uterine prolapse is not a subject that is easily explicated across all audiences. When people ask me what the causes of UP are, I struggle discussing the fact that the many of the factors that exasperate the condition are deeply entrenched in cultural practices that are discriminatory towards women. I recently read an article written by Dr. Elizabeth Enslin titled: “Social Equality: The Best Cure for Uterine Prolapse in Nepal” which illustrates the unique challenges of advocating for the prevention and treatment of uterine prolapse in Nepal. While it’s necessary to address the health needs of women who have developed various stages of prolapse via coordination across various government ministries, strengthening the health system and making health care accessible to women who would otherwise go untreated, the high prevalence of UP in Nepal will undoubtedly persist without effort to lessen what can only be described as gross social inequity between men and women in Nepal.

Who am I to walk into a country that I’ve never visited and espouse that the way things have always been done are causing significant harm to half of the population? Throughout my degrees in both health sciences and human rights I have been part of countless conversations about cultural sensitivity, but I’ve never found myself so blatantly confronted by a need to balance my western Judeo-Christian ideas about health and human rights with the cultural practices and beliefs of an entire country (to extent that certain beliefs can be said to be ubiquitous across the 125 caste/ethnic groups that exist in Nepal). This is one of the challenges that I’m working on trying to resolve (although I’m not sure that I will arrive at a satisfactory answer).

In the meantime, I’m going to narrow the scope in which I operate, all the while remaining aware of some of the broader challenges of advocating for women’s right to reproductive and sexual health in certain contexts. I’m going to take things one day at a time, without becoming overwhelmed by the larger issues. Ultimately, I want to do all that I can to strengthen Care Women Nepal as an organization to give them all of the tools that they will need to continue to play an invaluable role in bringing healthcare to women suffering from UP in Dhankuta.

My time in Nepal is short, but I’m hopeful that this is only the beginning.

Posted By Rachel Petit (Nepal)

Posted Jun 11th, 2017