ADVOCACYNET 399, October 4, 2023

Malaria In Retreat as Tribal People Mobilize in India

Net Assets: The NGO Lifeline purchases mosquito nets for pregnant and lactating tribal women in Odisha State and helps them to use the nets effectively. Photo by Surajita Sahu.

Braving extreme heat and a raging monsoon, tribal people in the Indian state of Odisha have succeeded in dramatically reducing the incidence of malaria in ten tribal villages in less than a year.

The malaria campaign is supported by Jeevan Rekha Parisad (“Lifeline”), a prominent NGO in Odisha, and funded by The Advocacy Project (AP).

Dr Manoranjan Mishra, who heads JRP, said in a Zoom call that the number of cases among a sample group of 3,000 villagers fell from 167 a month before the campaign began to 21 cases in October. One villager had died, he said, compared to 6 recorded deaths last year.

The achievement is seen as a major success in a state which registered 23,713 cases of malaria in 2022 – one of the highest rates in India.

The campaign began in the spring by identifying and prioritizing 3,000 vulnerable villagers, starting with 500 pregnant and lactating mothers. After focus group meetings found a dangerous lack of awareness about the threat from malaria, the JRP team embarked on intensive education to change behavior, offer speedy treatment to the sick, and remove stagnant water and brushwood where the larvae breed.

Dr Mishra said that the results so far have raised hopes that the campaign can reach single digits by the spring of next year and possibly even eradicate malaria completely among a targeted population.

“This is really encouraging and much better than we expected,” he said. “It shows what can be done when communities get engaged.”

*

JRP’s malaria campaign has drawn heavily on lessons learned from a COVID initiative last year, also supported by AP, that secured full vaccinations for 876 tribal people in two villages at a total cost of $1,054.

The decision to confront malaria was taken after it became clear that the state of Odisha would not become malaria-free by the end of 2024, as the government had hoped.

Tribal people are particularly vulnerable because they live in isolated villages and forest areas that lack medical services and are breeding grounds for mosquitoes. But the threat is also made worse by tribal customs and superstitions, explained Rohit Samal, a member of the JRP team and an AP Peace Fellow.

In one blog Rohit describes meeting Jhari, an elderly tribal woman, who took her son-in-law Bharat to see a witch doctor after Bharat began to suffer from fever, thinking that his symptoms were caused by “evil spirits.” The witch doctor performed a series of rituals on the young man that were “unorthodox, cruel, and terrifying,” before Bharat died, writes Rohit.

Even clothing and sleeping habits add to the risk. The traditional tribal clothing for men, known as a veshti, leaves much of the body exposed when a villager is working in paddy fields, knee-deep in water. Many villagers also sleep outside with minimal clothing during periods of extreme heat. But sleeping indoors next to an open toilet also attracts mosquitoes.

The biggest problem is a lack of mosquito nets, which are provided free by the government but were not available in the ten villages this year because the local authorities ran out of stock. Even when nets are available, most tribal families do not know that nets must be washed every month if they are to last the full three years, said Dr Mishra.

*

JRP’s campaign began in the spring shortly before a heat wave so intense that people were advised to stay indoors after 11 am.

Once the heat subsided, JRP visited the ten villages, created focus groups, and secured the collaboration of ten Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) who live in the villages and monitor pregnant women. Together, they identified the 3,000 vulnerable villagers and marked the homes of pregnant and lacating women with red paint. JRP also purchased and stockpiled mosquito nets and drugs in each village.

Surajita Sahu, a JRP project coordinator, explained that the ASHAs keep records on beneficiaries and make regular visits. If someone is feverish, she or he receives paracetamol and a blood test. In the event that malaria is detected, the patient receives chloroquine tablets and is closely watched. If symptoms become critical the patient is taken to one of two government health centers.

So far this year the program has worked with 311 pregnant women, given out 217 nets, performed 367 blood tests, and dispensed 327 chloroquine tablets. Nine of the 311 women had to be referred to a medical center.

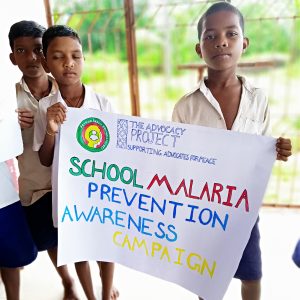

These treatment measures have been accompanied by intensive education and outreach that draw on popular local tribal culture, including Pala dances. JRP has organized village meetings, sponsored wall paintings, held art competitions in schools and sent a van festooned with posters, known as the “chariot,” to spread the word in the villages. The project even engaged a sand artist to portray a huge blood-sucking mosquito at a nearby beach that attracted large crowds before it was washed away.

In addition, thirty-four villagers have volunteered for Water Sanitation Committees in three of the villages and cleaned out large ponds which were breeding mosquitoes. JRP has also released over 1,500 gambusia fish into ponds to eat the larvae.

According to Biraj Krishna, around 4,600 villagers have been reached by the campaign so far this year.

All of this has produced a dramatic change in behavior. Focus group meetings suggest that over 30% of the target group – 900 people – are using mosquito nets. The number of women seeking advice from ASHAs and health centers has also risen sharply.

*

JRP team members are now exploring ways to keep the momentum going and scale up the program in 2024.

Biraj Krishna, who heads the JRP field team, said much will depend on the community activists who have received extensive training from JRP this year. As well as the ASHAs, they include child nutrition specalists known as Anganwadi workers who monitor children under five, women’s self-help groups, Water Sanitation Committees, and four government Auxiliary Nurse Midwives who treat patients at health centers and make visits to the villages.

The program will also draw on the local knowledge of villagers, and their use of plant-based solutions. Dr Mishra said that tribal people burn leaves and seeds of the Neem tree to produce smoke that deters mosquitoes, and also smear Neem oil on their skin as a repellent. But a bottle of Neem oil costs 450 rupees ($5.4) – a day’s wages in the villages – and only lasts for about a week.

As a result, AP and JRP are developing a start-up to produce free Neem oil for all ten villages. Dr Mishra expressed the hope that this would also interest the Indian government and World Health Organization, which are seeking to reduce the use of chemical insecticides and also counter the growing resistance of malaria parasites to drugs. JRP is also helping villagers to develop a natural alternative to Phenyl, a disinfectant that they use to clean toilets.

“There is a lot of local wisdom and talent among tribal people,” said Dr Mishra. “This will play an increasingly important role in malaria eradication and prevention.”

Stuff of nightmares: Lifeline uses sand paintings to draw attention to the threat from malaria, and urges villagers to sleep inside where possible, under nets, and clothed.

Photos by Surajita Sahu and Biraj Krishna

**