ADVOCACYNET 394 May 3, 2023

Ugandan War Survivors Describe Forced Pregnancy and Marriage

By Iain Guest

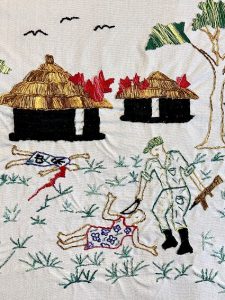

Victoria Nyanyjura founded Women in Action for Women after escaping from LRA rebels in Uganda. The picture by Margaret Akello, another WAW survivor, depicts Ms Akello’s rape.

Years later, when Margaret Akello used embroidery to describe her years of captivity by Ugandan rebels, she showed a desperate woman being savaged by a lion, as seen in the photo.

The powerful image is part allegory and part fact. The possibility of being attacked by wild animals in the jungle was ever-present. So was the threat of rape from her captors.

Ms Akello is one of thousands of women who were abducted as girls and forced into sexual slavery by fighters from the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel movement that devastated northern Uganda between 1987 and 2006. She is also one of ten survivors who have told their stories through stitching.

Several stories were displayed recently at the Cardozo Law Institute in Holocaust and Human Rights in New York during a meeting to review the case of Dominic Ongwen, a former LRA commander who has been sentenced to 25 years in prison by the International Criminal Court.

The court found Ongwen guilty on 61 counts, including 19 counts of sexual and gender-based crimes. His sentence was confirmed on December 15 last year by the ICC Appeals Chamber, which has also invited submissions from legal experts about the implications of the case for international criminal law.

These formed the basis for the recent meeting, which brought together feminist lawyers, experts in transitional justice, and two survivors of LRA atrocities.

The embroidered stories offered a dramatic backdrop to the legal arguments. They were presented by Victoria Nyanyjura, one of 139 female students abducted by LRA fighters from St Mary’s College in the village of Aboke on October 10, 1996. The crime attracted international attention after Sister Rachele Fassera, deputy headmistress at the school, followed the rebels and persuaded them to release 109 girls. The remaining 30 girls, including Ms Nyanyjura, spent years in captivity. Five have since died.

Following her own escape, Ms Nyanyjura formed Women in Action for Women (WAW), an association for women survivors of sexual violence, and requested support for embroidery training for her group from The Advocacy Project. The stories were stitched in July 2021 and turned into quilts in the US. They can be seen here with profiles of the artists.

Describing herself as an “activist and peace-builder,” Ms Nyanyjura praised the Cardozo institute for inviting survivors to the recent meeting, and asked for more regular contact between survivors and legal experts in future.

Survivors offer essential context and reliable partnerships, she said: “Listening here you can tell we are all in this together. If you work with people really affected you will ensure the sustainability of peace. NGOs will come and go. (We) are going nowhere.”

*

The use of sex slaves was central to the LRA’s war strategy and is depicted in excruciating detail by the WAW artists. Once in captivity, girls were distributed among LRA fighters and subjected to what the ICC charge describes as “forced conjugal relations.” The case against Ongwen centered on his treatment of seven “wives.”

According to a report by CAP International and Watye Ki Gen (‘We Have Hope’), an organization for survivors in Uganda, captive girls who had not reached the age of menstruation were known as “ting tings” and supposed to be exempt from molestation.

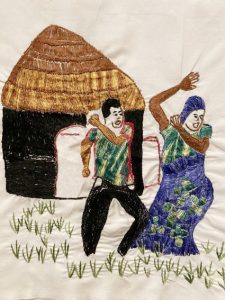

But this did not save Mary Atim, a WAW artist who was nine when she was abducted and given to a rebel. Ms Atim was then beaten by the man’s older wives and made to wash clothes. Grace Awor, another artist, depicted her own rape by a rebel in graphic detail.

Although relationships were intimate and prolonged many survivors never learned the names of their husbands, who used code names to avoid being identified. Most of the men died from disease or battle.

The threat of death, exhaustion or injury was always present. Judith Adong’s story shows a woman carrying a heavy load while an armed fighter pushes her forward with a machete. One of Christine Akumu’s stories shows someone stepping on a landmine left by retreating rebels.

*

Returning to normal life has created new problems by forcing the women to fall back on their own resources, often without the support of family or friends.

After escaping, many faced stigma and suspicion when they arrived home with their children and several sought new partners, only to be abandoned again. Christine Akumu was so desperate that she moved in with the brother of her rebel “husband.” She gave birth to two more children before being driven from the home.

Forced pregnancy has left indelible scars on the mothers and children. Past conflicts have highlighted the anguish of women who gave birth following rape and were torn between loving their children and living with a visible reminder of their ordeal. The WAW artists express nothing but love. Christine Akumu’s three children wanted to go to school, she explains, but she could not pay for their school fees. This has left them “bitter.”

As for the children themselves, Angela Atim Lakor from Watye Ki Gen told the meeting that most lack ID cards because their fathers cannot be identified. In addition, many were probably born in the jungle outside Uganda. This has made it even harder for them to attend school.

Adding to the anxiety, many survivors have found themselves living near former LRA fighters who have benefited from a Ugandan government amnesty. Several WAW artists still suffer from injuries they sustained in the jungle, and some even carry bullet fragments. Grace Awor’s wound has never been properly treated and is still leaking pus.

In spite of everything, the survivors are remarkably free from anger. Asked how she felt about Ongwen’s 25-year prison term, Ms Nyanyjura noted that Ongwen had been a victim himself because he had been abducted by the LRA at the age of nine before rising through the ranks. His sentence struck the right balance between justice and compassion, she said, while expressing the hope that this would ease Ongwen’s own reintegration into his village when he leaves prison.

*

Summing up the challenges that face survivors in a keynote address at the recent meeting Beth Van Schaack, the US Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice, noted that the path to recovery is constantly changing and that every woman’s experience is unique. This, she said, called for a creative, flexible response.

Of all the different approaches, the legal option may be most clear-cut.

Before Ongwen, sexual and gender-based crimes had been barely tested in an international court of law. Two celebrated decisions by the international tribunals on Rwanda and the Former Yugoslavia established that rape in war can be an act of genocide and a form of torture.

But the Ongwen trial was the first to successfully prosecute forced pregnancy and forced marriage, which are listed as war crimes and crimes against humanity in the ICC Statute. Lawyers at the recent meeting expressed satisfaction that both crimes are now established law as a result. This, they said, creates an important precedent for future cases.

Patricia Viseur Sellers, a senior advisor to the ICC prosecutor, also noted that women and children held by the LRA had been victims of slavery, which has been well tested in international law. This too could broaden the case against future perpetrators of sexual and gender-based violence.

At the same time, the legal path ahead is not without obstacles. Sarah Kasande, who heads the office of the International Center for Transitional Justice in Uganda, noted that a Ugandan law providing reparations and justice for survivors is stalled and has yet to be presented to parliament.

*

However significant the legal advances, legal redress may not be the most urgent need facing survivors. While human rights lawyers focus on accountability, survivors have set themselves a broader goal which Ambassador Van Schaack described as “returning to a life path of their own choosing.”

Being able to tell their stories and explain their version of the truth is particularly important. Some experts feel that rape victims should not be identified, to avoid their re-traumatization. But Ms Nyanyjura said that her WAW colleagues had made a clear choice to publish their stories. Their profiles were written in the summer of 2021 by Anna Braverman, a graduate at the Fletcher School, Tufts University, who was deployed by The Advocacy Project to volunteer with WAW and became close friends with the artists.

Ms Nyanyjura also said that speaking to the Cardozo conference had boosted her own confidence and expressed deep gratitude to the organizers and to UN Women, which paid for the travel of Ugandan participants.

“I am happy,” she said. “I must say we were respected.”

*

Of all the needs facing survivors, none may be more essential than earning a living.

Most survivors returned from captivity without an education or skills. Judith Adong starting training to be a tailor but gave up because of chest pains from her time as an LRA porter. The COVID pandemic also brought new pressures (which the WAW artists have described in this quilt). No sooner did Concy Alam open a restaurant than she was forced to close by the lock-down.

The ICC decision on Ongwen has opened the door to reparations through a trust fund for victims which has been established under the ICC although it operates independently. Uganda was the first government to refer a case to the ICC and this – plus the notoriety of the LRA – will likely ensure that any compensation is significant.

But the ICC depends on voluntary contributions from member states and does not qualify for funding from the US government, which has yet to join the ICC and deeply distrusts the court.

In addition, ICC reparations will only be given to those who are directly affected by the court’s judgements. This appears to exclude eight of the ten WAW artists, who were held by LRA units other than the ‘Tinia brigade’ commanded by Ongwen. Several speakers warned that reparations can create strains between survivors if mishandled.

Even being labelled a survivor may complicate the search for support. While humanitarian funding exists to help survivors attend meetings and trials, economic development is handled by a different set of donors that often find it difficult to work with small community-based groups like WAW.

Ms Nyanyjura said that WAW members hope to continue with embroidery, and several members have sold pieces through the new online store Southern Stitchers. But building a business will require sustained investment, as well as professional expertise, training and marketing skills.

This underscores the importance of a creative response, as suggested by Ambassador Van Schaack. It also requires an understanding not just of the problems faced by survivors but their resilience and the skills they have developed during their long journey.

Click here to purchase WAW embroidery and meet the artists

Iain Guest is Executive Director of The Advocacy Project

Victoria Nyanyjura founded Women in Action for Women after escaping from LRA rebels in Uganda. The picture by Grace Awor, another WAW survivor, depicts Ms Awor’s rape.

**