ADVOCACYNET 391 January 9, 2023

Community Campaigns Vaccinate Against COVID, Improve Access to Health Care

Community campaigners in the Global South have secured 5,393 vaccinations for vulnerable people in Kenya, Zimbabwe, Uganda, Bangladesh, and India, ensuring that the beneficiaries will not just be protected against COVID-19 but also receive better government health care in the future.

The campaigns have been managed by partners of The Advocacy Project (AP) since the summer of 2021, at a cost of $6,318.

A sixth campaign, by Backward Society Education (BASE), an advocate for the Tharu people in Nepal, opened the way to thousands more vaccinations in 60 villages.

Click here for photos from the six campaigns.

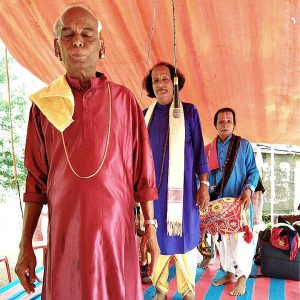

The most recent campaign concluded last month in the Indian state of Odisha after fully vaccinating 876 tribal people in two villages, Baberi and Mitukuli. Before the pandemic, both villages were inaccessible by road and were rarely visited by government health workers.

“If the services won’t go to the people, then people must go to the services,” said Dr Manoramjan Mishra, describing the approach of his organization Jeevan Rekha Parisad (‘Lifeline’), which led the campaign in Odisha.

*

The threat to tribal people in Odisha is a classic case of “vaccine inequity,” in which marginalized communities are unable to secure vaccinations even in countries that otherwise have stellar vaccination records.

Around 70% of all Indians have been fully vaccinated – higher than the global average (66%). But Dr Mishra said that vaccines have hardly penetrated into many tribal areas in Odisha state, which recognizes 62 different tribes and has the third largest tribal population in India.

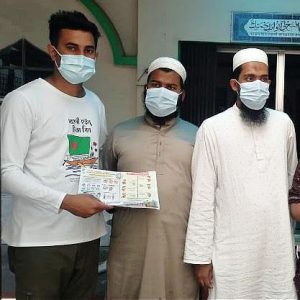

Vaccine inequity has also affected River Gypsies who live on the rivers of Bangladesh, another community supported by AP that struggles with isolation and poverty. AP’s partner, the Subornogram Foundation, works with Gypsies on an island (Mayadip) which has no health center.

The 60 villages where BASE worked in Nepal are also remote and are served by just three government health centers.

Dr Mishra in India said that such isolation leads to a dangerous lack of knowledge. When his organization started to work in the two tribal villages, he said, pregnant women were unaware that they were entitled to a month of rest at a government health center before delivery. As a result, many women delayed the trip until they went into labor and some even had to be carried in wheelbarrows through the woods. Others opted for delivery in their homes, which can be dangerous for the mother and child.

The vaccine imbalance between affluent neighborhoods and under-served communities is also pronounced in Africa, where vaccination levels remain far below the global average.

The first vaccination campaign supported by AP was launched in June 2021 by women in the informal settlement of Kangemi in Nairobi, where the health center was not equipped to store vaccines. In Gulu District, northern Uganda, people with a physical disability had no way to reach health centers during the frequent lock-downs.

*

All six campaigns supported by AP have relied heavily on motivated leaders and volunteers. Those in Kenya, Uganda and Nepal were led by women who had a close shave with COVID-19 and emerged fiercely determined to protect others. Emma Ajok, who led the campaign by the Gulu Disabled Persons Union (GDPU) in Uganda, described her ordeal in a blog.

The vaccination drive in India was spearheaded by four women, known as Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), who live in the villages and receive a small government stipend but have no formal medical training. In Nepal, BASE selected and trained a volunteer from each of the 60 villages to serve as point persons for the campaign.

Subornogram’s campaign on Mayadip island in Bangladesh was led by student volunteers and enthusiastically endorsed by Mohammad Anisur Rahman, the island’s religious leader.

Each campaign began with intensive education. The team in India used performances of the Pala, a local tribal dance, to spread the word. The campaigners in Kenya, Uganda, Zimbabwe and Bangladesh designed tee-shirts that carried the same message (“Be Brave – Get Vaccinated!”) and proved popular with volunteers and health workers.

The next stage was accompaniment. In India, the four health activists (ASHAs) walked with villagers to four vaccination camps at health centers near the villages, where jabs were administered by nurses and doctors. In Kangemi, Nairobi, 30 women formed an advocacy group and persuaded health workers from the affluent Westlands neighborhood to conduct vaccination camps in their settlement. They then went door to door in Kangemi to get people out.

In Bangladesh, the students ferried River Gypsies from Mayadip island to a government hospital on the mainland and back. In Uganda, an ageing GDPU vehicle took a total of 200 people with a disability to the Anaya health center. Transport accounted for over half the cost of both campaigns.

In Nepal, BASE recruited a doctor to visit all 60 villages and administer antigen tests. Villagers who tested positive were helped to self-isolate by their village volunteer, while more serious cases were taken to government health centers.

*

All six campaigns have relied on partnership between civil society and local government, and organizers said this will help the government to improve health services in villages in the future. BASE and AP purchased oximeters and personal protective equipment (PPE) kits for the three government health centers covered by the campaign in Nepal.

The campaigns have also shown the power of information. Pinky Dangi, who managed the BASE campaign in Nepal, explained that the rate of infection fell sharply in the 60 villages after BASE’s initial outreach, and that most villagers have now been fully vaccinated.

In India, Dr Mishra said that more pregnant women from the two tribal villages are now visiting the health centers to await delivery well before they give birth, while home deliveries have fallen. He also expressed the hope that lessons learned from COVID-19 can be used to combat future health threats.

Emma Ajok noted one final benefit from GDPU’s successful vaccination drive in Uganda – a strengthening of GDPU’s credibility with its members. “They wanted to see us act,” she said during a recent phone discussion. “They were very appreciative of what we achieved.”

Next: Tribal people in India take on malaria

Learn how partners responded to the pandemic in our 2020 and 2021 annual reports

|

|