The Bosnian war led to the displacement of over 2 million people or half the country’s population. Many of these people have returned to their pre-war homes, while 117,000 people remain internally displaced and 7,500 of them are still living in refugee centers.

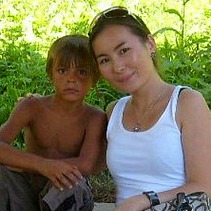

I visited Mihatovići, one of the main refugee centers in Bosnia and the largest one in the Tuzla canton. Nezira, a Bosfam weaver, has been living in Mihatovići for the past 14 years. Two of her daughters have married and moved out, and she now lives with her youngest daughter, Almedina. Almedina brought me to Mihatovići and showed me what has become her home since she was six years old.

For a first-time visitor like me, getting to the refugee center was quite a challenge. As Mihatovići is situated on a hill about 10km from the city of Tuzla, our trip involved riding a crowded bus for 30 min and hiking for about 20 min. Climbing up a steep hill in the heat of 35°C (95F) was certainly no fun.

Mihatovići was built in 1993 with Norwegian aid. Once, the residents of this collective center numbered in thousands, but now it is a home to approximately 500 people. Most of them are from Srebrenica and the nearby towns such as Bratunac and Zvornik. The center consists of two-story houses neatly lined up in rows and colored in blue, pink, or yellow. Each house has four apartments, and each apartment is occupied by one family. However, when a large number of people arrived in Mihatovići in 1995, three families had to live in one apartment. This meant that up to 20 people shared a small two-bedroom apartment with an open kitchen and a bathroom.

At the refugee center, I saw mostly women, children, and elders. The prevalence of households headed by females is partly explained by the fact that many of the Mihatovići residents are survivors of the Srebrenica massacre. Employment among these women is very low; they support themselves and their families based on limited social welfare payments.

Besides the refugee houses, Mihatovići has two little grocery shops and a primary school. When children finish the primary school, they start commuting to Tuzla for continuation of their education. A doctor comes only on Tuesdays, despite the large number of sick elders who need regular medical care. When I visited Mihatovići, the residents hadn’t had running water for three days; a nearby spring had become their only source of water. There is no government representation or a person in charge of the collective center. If people have a problem such as lack of water, they try to solve it on their own or simply wait until the problem is resolved by itself. The government used to provide food, clothes, and bus tickets, but now accommodation is the only thing that the refugees receive free of charge.

Bosnia plans to close all collective centers by 2014 in order to facilitate the return of refugees. However, many refugees, especially those from the Srebrenica area, do not want to return. The complete destruction of the town’s economy, drastic change of ethnic composition, and the occasional harassment of returnees make Srebrenica nothing like what it was before the war. The government and some aid organizations provide assistance to the refugees only if they want to return to their pre-war homes. If they choose to live in a different place, they are on their own.

If Mihatovići is closed down, Nezira will go to Srebrenik to live with her elder daughter, instead of returning to her house near Srebrenica. Every day, she will have to commute to Tuzla for an hour and a half to work at Bosfam. The condition in Mihatovići is not pleasant, but closing it down and pushing the refugees to return to a dead town like Srebrenica is not a durable solution to displacement. It seems like the world has forgotten about Bosnian refugees. Perhaps it is because Bosnia is no longer a hot spot like Afghanistan or Sudan.

Posted By Laila Zulkaphil

Posted Jul 24th, 2010