This week has been an eventful one in Lima. The mood is festive, with pre-celebrations of the Fiestas Patrias taking place (the national independence day is on July 28th) and Peru’s unexpected qualifications to the semi-finals of the COPA América, the importance of which anyone having spent some time in fútbol-crazy South America will be well aware of.

On Sunday night, as I was deafened by the fireworks marking the culmination of the annual, exuberant parade announcing the Fiestas Patrias, I was reminded that merely two decades ago, Lima was experiencing an altogether different kind of explosions. In fact, aside from the glitz and the joyfulness—and, I feel, overshadowed by them—this week was also the anniversary of two tragic events dating from the period of the Peruvian political violence. Both occurred in 1992, and each is sadly emblematic of the barbary reached by the two sides in the conflict.

The first event, the Tarata street bombing, was authored by members of Sendero Luminoso. Throughout 1991 and 1992, the terrorist organization had gradually shifted its focus away from the Peruvian highlands, and Lima had become the principal target of its subversive actions, forever imprinting the expression of “coche-bomba” (car bomb) into the memory and vocabulary of every Limeño and Limeña.

The first event, the Tarata street bombing, was authored by members of Sendero Luminoso. Throughout 1991 and 1992, the terrorist organization had gradually shifted its focus away from the Peruvian highlands, and Lima had become the principal target of its subversive actions, forever imprinting the expression of “coche-bomba” (car bomb) into the memory and vocabulary of every Limeño and Limeña.

The most remembered of “coche-bomba” attacks is probably the bombing of Tarata street, in the center of the financial and commercial district of Miraflores (and a short 10 minutes walk from my current home). In the evening of July 16th, 1992, two vehicles containing more than half a ton of explosives were set off, killing 25 and injuring 155 bystanders, and dispersing any remaining notion among Limeños that the Peruvian internal conflict was occurring out there, to others.

In response to the Tarata street bombing and many other “coche-bomba” attacks that followed, in the early hours of July 18, 1992, the “Grupo Colina”, a secret paramilitary commando made up of intelligence army officers as part of a clandestine government war against subversion, entered the Universidad Nacional de Educación La Cantuta to sequestrate, execute, and disappear nine students and a professor.

La Cantuta, as numerous universities in the country, had a leftist reputation, and its students had indiscriminately been labelled as terrorists by the government and the military. Immediately following the event, and despite the testimonies of hundreds of witnesses, the massacre was denied by military authorities. The calcined remains of some of the bodies were discovered the following year. It was later revealed that the students and professor had been transported to a remote location where they ended up with gun shots to the head. The bodies were buried and later burned and re-buried in a different location to conceal what had happened.

La Cantuta, as numerous universities in the country, had a leftist reputation, and its students had indiscriminately been labelled as terrorists by the government and the military. Immediately following the event, and despite the testimonies of hundreds of witnesses, the massacre was denied by military authorities. The calcined remains of some of the bodies were discovered the following year. It was later revealed that the students and professor had been transported to a remote location where they ended up with gun shots to the head. The bodies were buried and later burned and re-buried in a different location to conceal what had happened.

In 2009, Fujimori was sentenced to 25 years in prison for his responsibility in the Cantuta case, among others. Last Friday, I attended a march organized by the relatives of the Cantuta victims and various human rights organization in commemoration of the 19th anniversary of the massacre and against the possible pardon to Fujimori (this deserves a much longer entry, and will be the topic of my next post).

All in all, then, it has been a big week for memory. The anniversary of these two events once more highlighted the divided nature of Peruvians over the period of the political violence and the polemical figure of Fujimori. A cursory glance at the comments section of this news report on the commemoration of Tarata confirms it: countless comments thank the ex-president they affectionately call “el chino”. Many decry the fact that his role in eliminating the terrorists is not mentioned, for instance, in the Tarata commemoration. Others specifically refer to the Cantuta case, thanking Fujimori for eliminating “esos terrucos” (terrorists). More worryingly yet, a good number blame human rights for getting in the way of the proper recognition Fujimori supposedly deserves.

As controversial as they may be, the commemoration of Tarata Street and La Cantuta at least allow for a dialogue to occur over what happened, they allow for the slow and continual construction of memory, and, perhaps even more importantly, they provide the relatives of the victims with an outlet for their grief and the reaffirmation of their commitment to the search truth and justice.

The same cannot be said for the wide majority of the massacres that occurred in the Peruvian countryside, particularly during the first decade of the country. Tarata Street and La Cantuta represent both sides of the conflict, but only in its urban dimension. In rural areas, people’s memories of the events are rarely if ever provided with the opportunity to be externalized in this way; they are repressed, yet not forgotten.

These past few weeks, I have been working with relatives’ testimonials that were recorded by EPAF in 2009 in various communities affected by the violence. Listening to one testimonial after the other, I have had to fight back my own emotions at the authors’ evident inability to control theirs while recounting their story. I have interpreted this as a reflection of the unprocessed nature of people’s pain and distress over events that occurred more than 20 years ago, and as an obvious need for an outlet and recognition of the events that changed their lives in the worst possible way.

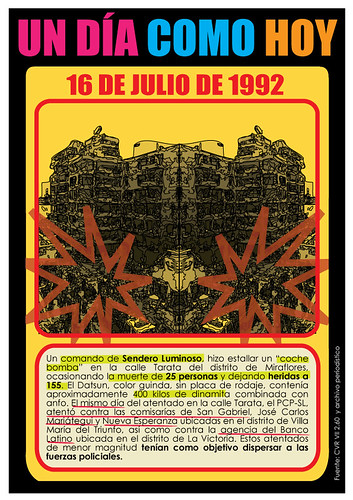

A wonderful initiative contributing to the construction and preservation of memory in Peru is the “Un Día en la Memoria” blog and calendar; for most days of the year, it uses newspapers records and the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to identify events that occurred on “un día como hoy” (on a day like today), supported by great graphic art. Here is the image for the Tarata street bombing:

Read the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report on the Cantuta case, in Spanish.

Read the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report on the Tarata Street case, in Spanish.

Read former AP Fellow Karin Orr’s blog post on last year’s anniversary of La Cantuta.

Posted By Catherine Binet

Posted Jul 19th, 2011