ADVOCACYNET 419, November 20, 2024

Conflict Survivors Demand a Say in War Reparations in Nepal

by Iain Guest

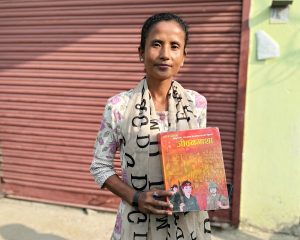

Sarita Thapa’s father disappeared during the war in 1999. She now works for a municipality, and shows how collaboration between local government and conflict survivors could help the search for reparations. The book profiles 680 cases of serious abuse committed in Bardiya District.

When I first met Sarita Thapa in 2016 in central Nepal she was still grieving for her father, Shayam Bahadur, who had disappeared after being seized by security forces in 1999 at the height of the Maoist rebellion.

The loss of her father had triggered an unimaginable chain of events for Ms Thapa and her mother. After being disowned by neighbors they were expelled from the village. Soon after, Ms Thapa’s husband died suddenly from a snakebite. Years later she still seemed overwhelmed by the unfairness of it all.

It was a different Sarita Thapa who joined a recent meeting of conflict victims and survivors in the town of Gulariya, Bardiya District. Ms Thapa now works for her local municipality, where she offers counseling to 159 other survivors. She has regained her self-confidence, and with good reason. This is a job that draws on her experience and earns the respect of others.

More than this, Ms Thapa’s work shows how collaboration between local government and survivors can help in providing reparations to those damaged by the conflict.

This discussion is now under way following passage of a recent law on transitional justice that set up a Reparations Fund and two commissions to investigate disappearances and promote truth and reconciliation, each with its own reparations unit. As well as providing compensation, many see reparations as a broad tool for helping communities and individuals to heal.

But the euphoria is also tempered by realism. Tens of thousands of Nepalis were affected by the war and the cost of full compensation could run to billions.

Such money will be hard to find, particularly as this is Nepal’s second attempt at compensation. Following the peace agreement in 2006, the government of Nepal created a peace trust fund which raised around $230 million, with the government contributing 60% and donors covering the rest. Survivors and family members were allocated around $8 million of “interim relief.”

The most serious cases received 1 million rupees ($7,575) in installments and I remember Ms Thapa complaining that the staggered payments had made it hard to invest in land or build a new house. One reason was the enormous strain placed on Nepal’s finances.

The prospects for another generous pay-out seem even dimmer at a time when humanitarian aid is reeling from the crises in Ukraine, Gaza and Sudan. One European diplomat in Kathmandu described his government as sympathetic but looking for reassurance.

*

This is well understood by survivors of the conflict, who have most at stake in the process and most to lose if it fails. They also understand the need to show that they can be reliable partners in the debate ahead.

“We have much to offer,” said Bhagiram Chaudhary, who heads the survivors’ group in Bardiya and lost his brother and sister-in-law during the war. “No-one knows the facts like us. But we also know we can’t expect a blank check.”

This is being discussed at meetings across Nepal like the gathering in Gulariya. Bardiya suffered more disappearances than any other district and the survivors here are among the best organized in the country. They formed a Conflict Victims Committee (CVC) in 2006 and opened the door to victims of abuse by both sides – Maoist rebels and government forces.

The same urge for inclusiveness inspired the creation of a broad-based National Network of Victims and Survivors of Serious Human Rights Abuses in 2022. The network lobbied successfully for the new law on transitional justice and has chapters in over 60 of the country’s 77 districts.

Bhagiram Chaudhary is general secretary of the national network and said that survivors offer a vast repository of knowledge. He also noted that the facts are well known – so much so that the Bardiya committee has published a book of the 680 most serious cases in the district.

Survivors see no need to re-open these cases from scratch. But they do expect the new commissions to establish definitive databases and offer survivors the chance to describe their experience in person – an essential part of healing. The Bardiya committee is eager to facilitate such face-to-face meetings.

*

The urgency of these local discussions contrasts sharply with the stuttering debate over transitional justice in Kathmandu, which stalled for years over legal accountability and political squabbling before passage of the recent law.

There is little sign of deadlock in Bardiya, far from the capital. Helped by a new constitution in 2015 that devolved power to the regions, and by the integration of Maoists into the political process, many municipalities have taken initiatives to address the needs of survivors and ensure that reparations go beyond financial compensation.

This has led to an explosion of creativity in the form of street theater, memorial parks, wall paintings, memorial quilts and family shrines. Many of these initiatives have been supported by Maoist mayors, who are achieving through peaceful means what they failed to achieve by war.

All involve close collaboration between local government and survivors, and Sarita Thapa’s counseling shows how this can also be made to work for reparations, with a nudge from donors.

Ms Thapa works for the municipality through the Centre for Mental Health and Counseling, a Nepali NGO that is active in communities and receives support from the Swiss government. The Swiss been active in promoting the new law on transitional justice and are said to be eager for practical solutions.

*

Some challenges seem beyond the reach of survivors. First and foremost, how do they put a price tag on their losses?

When I put the question to the recent meeting in Gulariya I was met with indignation and confusion. Laxmi Khadka sold her house and land after her husband was seized and assumed killed by Maoist rebels, over twenty years ago. “How much have I lost?” she asked. ‘Not less than 5 million rupees.”

Finding an acceptable formula will certainly be difficult. It might be possible to estimate the lost earnings of businessmen like Ms Khadka’s husband or Sarita Thapa’s father, but most victims in Bardiya were farmers who worked outside the formal economy and grew to feed their families.

Even if a formula can be found, the demands are bound to dwarf what is available. No one at the recent meeting was ready to accept less than 2 million rupees, which could amount to more than $10 million in Bardiya alone. And Bardiya is just one of 75 districts affected by the war.

Still the Bardiya committee is determined to take the initiative and show agency. It has submitted questionnaires to seventy families and plans to reach out to relatives of all 680 serious cases, while at the same time hoping that experts at the new reparations fund will point the way.

*

Survivors are more confident of ensuring that gender is factored into reparations. Over 9,000 women were widowed during the war, and they were the first to absorb the shock of a disappearance or killing.

Kushma Chaudhary, a skilled fiber artist who has worked with The Advocacy

Project since 2016, recalled how the disappearance of her father left her mother to manage the family’s land, care for seven young children (including 4 daughters) and deal with the suspicion of neighbors.

The anguish of widows was worsened by their inferior standing in a patriarchal society. At the time, Ms Chaudhary’s mother was forbidden under law from inheriting land owned by her husband (this is permitted under the new law). Nor could she officially declare her husband dead, and receive benefits, until his body was recovered. The education of her daughters also suffered.

The hard edges have softened over time. Ms Chaudhary’s six siblings are married and now provide her mother with a safety net. Also, Kushma was younger than Sarita Thapa when her own father disappeared and seems to have weathered the intervening years better. She said she would be grateful for whatever the family receives and will “trust the government to do its best.”

If they are accepted as genuine partners in the reparations debate, survivor committees will no doubt make sure such conciliatory messages are heard.

*

If the ultimate goal of reparations is to promote healing, the initiative will have to come from survivors in communities. This cannot be imposed.

Under the new law, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission will offer survivors and victims a chance to confront perpetrators and appeal to the courts if they are unsatisfied. But this will not address the social exclusion suffered by Sarita Thapa and her mother, which was more subtle than violent.

Ms Thapa hedged when I asked if she has settled her differences with the neighbors and relatives who drove her away after the disappearance of her father. “They have expressed regret for what happened,” she replied cautiously.

It sounded like an apology, but not quite. The same ambivalence will no doubt be felt across Nepal in the months ahead.

READ MORE

How Important is Justice to Healing After Violence? (September 30, 2024)

Conflict Survivors in Nepal Welcome “Historic” Agreement on Transitional Justice (August 19, 2024)

Nepali Survivor to UN Security Council: Families of the Missing Hold the Key to Peace (July 14 2024)

Travesty of Justice in Nepal (December 19, 2016)

Kushma Chaudhary was one of seven children left to support their mother after Kushma’s father disappeared during the conflict. Feeding the family has been the first priority.