Looking back on my childhood growing up in south Arkansas during the Civil Rights Movement, has made me realize how complicated and ingrained systemic racism is and how important it is to learn about its roots as we move to a more just society.

Southern Segregated Culture

It all comes down to education. We need to learn not only the good stuff about our country, but we should learn about–and from–our mistakes, too. The recent nationwide protests have produced many constructive, reasoned conversations on these painful topics and more people seem to be listening. Let’s hope substantial change comes from all of this soul searching. The world that we leave to our children depends on it.

I was born in Warren, Arkansas in 1954, the year of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka and three years before the desegregation of Little Rock’s Central High School. My hometown of 6500 was about 60% white and 40% black. No Latinos, Asians or any other ethnicities. No Jews and only a handful of Catholics. Most white and black people were church-going Protestants, but there was no mixing of the races in churches or in any other social context.

It was a forestry town where my father was the chief management forester of a large company that employed mostly white people, especially in the good-paying positions. It was a very segregated town. I would occasionally see black people doing domestic or yard work at someone’s house or I’d see them at the courthouse in the middle of town, but not very often in the stores and never in restaurants or the YMCA. And there was a separate entrance for the movie theater where black people could watch the movies from the balcony.

Civil Rights

In my own home during the 1960s, race was rarely discussed. Even when the various civil rights marches happened and when Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis in 1968, very little was said since those events occurred in big cities and had virtually no effect on our small-town lives. As far as I know, there was no KKK in my hometown and the few times that its activities were discussed at home, my parents did not approve.

Despite that disapproval and with other big issues such as the Vietnam War, women’s lib, and political and social unrest swirling around, I’m sure my parents felt they had enough to deal with and wanted to keep our lives as “normal” as possible. And people didn’t want to be ostracized by their communities by taking a stand against such injustices since it’s very hard to turn your back on the people who have loved and nurtured you your whole life even if you sense that something is inherently wrong with that social structure. Right or wrong, it was better to keep quiet and hope that things would work out. And thus we became a part of the “Silent Majority.”

School Integration

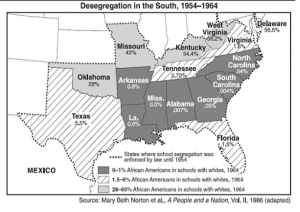

Despite the success of the Little Rock Nine in their brave quest to integrate the Little Rock Public Schools in 1957, desegregation moved very slowly through the southern states in the subsequent years.

Starting in the late 1960s a few black children were integrated into the white schools, but full integration didn’t happen until January 1970 when desegregation could no longer be legally avoided. Despite the middle-of-the-school-year disruption in our academic progress—different teachers, different textbooks, etc.—the transition was quite peaceful. Of course, there were a few white parents who sent their kids to private schools in Little Rock, but by and large, most people kept their kids in the public school system. Integrating the schools was a big step in the Civil Rights Movement and eventually the “separate but equal” restrictions went away, but life in my hometown still remained largely segregated especially in churches and social organizations.

Broadened Perspectives

After graduating from high school in 1972, I went to a small liberal arts college in Memphis which broadened my outlook on the world somewhat, mostly by meeting and studying with people of other ethnicities and orientations. Most of the students there, however, were from the deep South with a similar upbringing as mine.

Coming to DC for graduate school in the late 1970s though was, by far, the most eye-opening experience. Here were people from across the United States and all over the world, many drawn by jobs on Capitol Hill and other organizations associated with this world seat of power. Also, through my singing work in churches, synagogues, choral groups, and theaters, I met so many interesting and committed people of all races and creeds working and volunteering in a whole array of missions and organizations. What a great place to be during those years!

I eventually married and became the mother of four terrific children, all grown now. Their public school education and upbringing in Silver Spring, MD was quite different from mine, but I believe much healthier because their friendships were less limited by racial and ethnic barriers. (According to this report, four of the top 10 most diverse cities in America are in Montgomery County, MD.) Of course, there were–and still are–challenges, but overall, my children’s individual outlooks are more open to people of other backgrounds. And many of these younger people have enriched my own life.

As much as I have learned through the years, I occasionally still have to check myself. For several decades I’ve thought the Confederate flag needed to be banned, but didn’t give much thought to the Confederate names of schools, highways or other places. Sometimes I didn’t even know the names were from that era. I’d never heard of Albert Pike who was from Arkansas and a Confederate general or Jubal Early, another Confederate general.

So I’m very grateful to the current BLM Movement for bringing this information, as well as so many other things, to my attention. I personally think all of those recognitions—names of streets, buildings, monuments, etc.—need to be changed and Confederate statues removed from government and public spaces. Yes, they are a part of our history, but it is a shameful part of our history. Why do we want to honor that shame?

From Here On . . .

It all comes down to education. We need to learn not only the good stuff about our country, but we should learn about–and from–our mistakes, too. The recent nationwide protests have produced many constructive, reasoned conversations on these painful topics and more people seem to be listening. Let’s hope substantial change comes from all of this soul searching. The world that we leave to our children depends on it.

Posted By Intern1

Posted Jul 6th, 2020