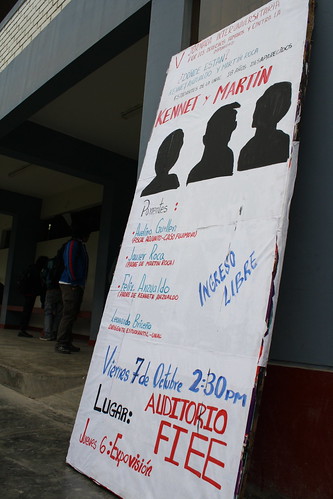

Two weeks ago I went to Callao, Lima’s port, to attend an event organized by the Coordinadora Contra la Impunidad (CCI). The conference was held at the Universidad Nacional del Callao during the 5th Inter-university Day for Human Rights and Against Impunity, and in commemoration of the 18th anniversary of the disappearance of two of its students, Martin Roca and Kenneth Anzualdo. Speaking were the respective fathers of the two students, Javier Roca and Felix Anzualdo, as well as EPAF director José Pablo Baraybar, who testified as an expert in the trial for the Anzualdo case.

Martin Roca Casas was detained by members of the Marines’ Intelligence Service on October 5th, 1993. He was never seen again. In the weeks previous to his disappearance, he had been the victim of harassment by intelligence officials, reason for which his father sought legal assistance, and Martin contacted Callao’s police department by writing to request guarantees for his life and personal safety; a request that was denied.

Kenneth Ney Anzualdo Castro was also a student at the university, and Martin’s friend. Since he had been with Martin on the last day the latter was seen, he was scheduled to testify at the prosecutor’s office regarding his friend’s disappearance. He never did, however, as he was himself disappeared by members of the Army’s Intelligence Service on December 16th, 1993. It was later established that, like his friend, he was detained, tortured, executed, and cremated in the basement of the Intelligence Service headquarters.

Despite the unrelenting efforts of his relatives, the disappearance of Martin Roca has occurred in complete impunity, as the case was archived permanently for a purported lack of evidence. Meanwhile, the Interamerican Court of Justice found the Peruvian State guilty of the enforced disappearance of Kenneth Anzualdo in 2009. According to the ruling, the State is obligated to investigate, take to court, and sanction those responsible for this crime, to proceed to the search and localization of his remains, and pay an indemnization to his family. This sentence has yet to be carried out.

This was the second university “conversatorios” I attended—a previous one was organized by EPAF back in September during the Pontifica Universidad Católica’s Human Rights Festival. At both events, the turnout was disappointingly low, despite EPAF’s best attempts at promoting the events.

I have been wondering about the reason behind this low attendance, trying to understand, for example, how it is that out of a total of 15,000 students at the Universidad Nacional del Callao, only a few dozens would be interested to learn about the abduction, torture, and execution of two of their own.

It may be the fact that this occurred 20 years ago; that students feel like this is not relevant to their reality. I had an interesting conversation about this with Marly Anzualdo, Kenneth’s sister. According to her, today’s youth are subtly (and not so subtly) taught not to question the “official” history of Peru’s dark period, even not to think about it. This indifference is very hard to break through.

During the period of political violence, the mere fact of being a student made you suspicious of being a terrorist in the eyes of the government. Military bases were even set up on the grounds of many universities. Consequently, as Javier Roca recounted during his presentation, many parents would tell their children to avoid becoming involved in any type of activities or protests on their campus. Which is exactly what the government wanted: “Leaders of this type always need people that are asleep, people that never do anything, so that they themselves may do anything they wish, as if they were on their plot of land. This is what happened.”

According to Javier, the general indifference to the themes being discussed at the conference suggests that this tactic has been successful. “In meetings, in Congress, in seminars, I always hear people ask: “Why did this happen?” But in this fight, I have found the resounding answer, and I no longer have doubts. This happened because, just like now, the rest of the country’s population was indifferent. Of all the people that were in the sector where [my son] was, no one did anything, no one said anything.” Javier continued: “I don’t know if one day, we will be able to shake ourselves up, react, and be able to show unity and protest when faced with an injustice.”

At the beginning of the conference, a representative of the Coordinadora Contra la Impunidad emphasized to those present that the goal was not merely for them to become more informed about what happened. The objective, rather, was for them to become actively involved in the search for justice and the truth; for them to mobilize their friends, their colleagues, and their families in this fight. Likewise, Marly Anzualdo concluded the conference by commenting that everyone had a responsibility to ensure that the death of her brother, and of so many others, not be in vain.

Javier Roca was one of the people interviewed and photographed in 2009 by Renzo Aroni and Jonathan Moller. Here is a video montage of the material I have produced for EPAF’s “Not One but Fifteen Thousand Voices” series.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QH55ci11PEA

Finally, following is a poem written by Marly Anzualdo in honor of her brother:

Kenneth – Hermano

Tú no tienes una tumba

Porque eres como el viento.Tú no tienes una tumba

Porque eres como el tiempo.Tú no tienes una tumba

Porque eres esperanza.Tú no tienes una tumba

Porque eres libertad.Tú no tienes una tumba

Porque tú no estas muerto.Tú naciste para vivir por siempre

Te amo.

To learn more about the Roca – Anzualdo case, visit the Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos – APRODEH’s page (in Spanish).

Posted By Catherine Binet

Posted Oct 16th, 2011