The Dosta! (Enough!) Quilt

Background

The Eight Roma artists with their finished quilt. In early 2011 AP asked the Council of Europe to support a project of advocacy quilting with Roma. It seemed like a good fit. The Council was a leading advocate for Roma rights in Europe, and AP had helped the Council launch the International Roma Women’s Network in 2003. Our experience with the Congo quilts had shown that quilting can empower women who have no other form of expression. Might quilting also empower the Roma, who are among the most marginalized people in Europe? AP’s Executive Director, Iain Guest, visited Strasbourg and pitched the idea to the Special Advisor on Roma Issues at the Council. Kerry McBroom, who had served as Peace Fellow in Sri Lanka and was living in Paris at the time, agreed to help. Kerry and Iain took one of the Congolese quilts to a group of Roma families that had been living precariously for some years on the outskirts of Strasbourg for some years (photo). Most were from Romania and had come to France in search of better economic opportunities. They had been expelled from France in June 2010, only to return. Many of the women now relied on begging for their livelihood.Eight women volunteered to participate: Dominica Nicola, Claudia Bercuta, Roxana Neda, Ecaterina Neda, Mihaela Moldovan, Ramona Stancu, Florea Neda (pictured laughing), Vesna Botti. Quilting began in February 2011, with Kerry McBroom acting as coordinator. Helped by a small grant from the Council of Europe’s Directorate of Culture, Cultural and Natural Heritage Kerry located a local artist and a Romanian interpreter, and organized a first meeting at the caravan site. It was not a success. Curious husbands and drunken strangers came by to look, much to the embarrassment of the women. The artists decided to move to a room at the Council of Europe.  Show and Tell: Irene Weidmann from the Council of Europe and Kerry McBroom, Peace Fellow, used one of the Congolese quilts to explain advocacy quilting at the Roma caravan site outside Strasbourg. Kerry worked with the Council to manage the project. The eight women had no previous experience of handicrafts before making the quilt, but they quickly grasped the concept and selected themes that mattered most to them: insufficient food, poor services, ill health, early marriage and begging. These were depicted in harsh detail. One tile showed a police raid and deportation. Another showed shortages of food and medicine. Several tiles showed begging and domestic violence. Like their Congolese counterparts, these Roma artists used quilting as a tool of denunciation but as in the Congo, the quality of their needlework was exquisite. They decided to name their quilt Dosta! which means “Enough!” in Romany. Dosta! is also the name of a campaign by the Council of Europe. Over the next two months, the eight women worked in harmony under the watchful eye of Kerry and Eleni Tsetsekou from the Council. Producing panels brought the artists together, and provided something of a respite. One of the most active artists, Floreda Neda, said that quilting enabled her to escape her “fatiguing, depressing and dehumanizing” daily activities as a beggar. Claudia Bercuta, a single mother, hoped that her panel would encourage young Roma boys like her son, Ellis, to respect women. Over the next two months, the eight women worked in harmony under the watchful eye of Kerry and Eleni Tsetsekou from the Council. Producing panels brought the artists together, and provided something of a respite. One of the most active artists, Floreda Neda, said that quilting enabled her to escape her “fatiguing, depressing and dehumanizing” daily activities as a beggar. Claudia Bercuta, a single mother, hoped that her panel would encourage young Roma boys like her son, Ellis, to respect women. The Dosta! quilt goes on display: The Dosta! quilt was no sooner completed than it was much in demand. The quilt was first displayed in the atrium of the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, where Maud de Boer-Buquicchio, Deputy Secretary-General of the Council of Europe, met and congratulated the artists on May 29 (pictured below).  Group Effort: Putting the finishing touches to the quilt at the Council of Europe. The quilt then travelled to Venice, where it was exhibited at the prestigious Biennale Festival as part of an exhibition on Roma culture sponsored by the Open Society Foundations and the Council of Europe. Known as Call the Witness, the exhibition featured testimonies and works of art on Roma. Ms. de Boer- Buquicchio, one of the speakers, built her address around the quilt which she described as “a way of rendering the invisible Roma women’s lives visible.” Robert Palmer, director of the Council’s Directorate for Culture, Cultural and Natural Heritage, also spoke at the opening of the Roma Pavilio. The Council posted a video of the speeches. The quilt provided a backdrop for a succession of well-known speakers, including the author Salman Rushdie who suggested that “people who are nomadic…have to find different ways of understanding themselves in the world.” Maria Hlavajova, curator of the event and artistic director at BAK, in the Netherlands, gave an interview about Roma culture in a multicultural but increasingly intolerant Europe. The Dosta! Quilt was next shown in October 2011 in Granada, Spain at the 3rd International Conference of Roma Women. The Conference was organized by the Council of Europe in cooperation with Spain’s Institute of Gypsy Culture (Instituto de Cultura Gitana), the Spanish Government and the International Network of Roma Women (launched in 2003 with help from AP). During the summer AP had produced three new Roma quilts, from the Czech Republic and Kosovo, and the four quilts were hung outside the conference hall to illustrate the intense discussion taking place inside. AP produced a short video on the conference. The next port of call for the Dosta! quilt was Kean University in the US. All five Roma quilts were included in the exhibition of advocacy quilts, which ran from January to September 2013. Four of the quilts, including the Dosta! Quilt were then shipped to the Institute of Italian Culture at Marseilles, where they were due to be exhibited at a large cultural festival in November 2013. Quilting as Change: As well as telling the story of Roma women in France, the Dosta! Quilt has produced a dramatic improvement in the lives of the eight artists. At the urging of the Council, the mayor of Strasbourg agreed to provide the quilters with housing and a work permit in recognition of their fine work. Eleni Tsetsekou, from the Council, summed up this important outcome: “I can confirm that all of the women who participated in our little project have been relocated with their families by the City of Strasbourg to a new site just behind the station. They have water, electricity, washing machines etc. The city government is seeking a way to integrate them into commercial life, through a training and apprenticeship in French. All the children are in school and none has dropped out. The people at the Mayor’s office who are managing this are impressed by the civility of our Roma partners. So for the moment, the news is all good.” This signal achievement showed that advocacy quilting can produce real change and improve the lives of Roma. The director of the Human Rights Center at Norway University wrote to ask: “This is quite remarkable. Will you be following this over time?” Irene Weidemann, from the Council’s Cultural Department, wrote: “The women have a real talent. I am also impressed at the concrete impact the quilt in Strasbourg had on the municipality for the benefit of the women and their families.” Ms. de Boer-Buquicchio, the Council’s deputy Secretary-General who had done so much to champion the quilt, summed it all up: “This is really great!“ |

The Quilt is Unveiled: Eleni Tsetsekou from the Council of Europe steered the quilt project through to a successful outcome, and lobbied the government of Strasbourg on behalf of the quilters. Eleni and the eight artists presented the finished quilt to Maud de Boer-Buquicchio, Deputy Director-General of the Council. |

On Display: the Dosta! Quilt at Kean University. |

Artists

Artists

Vesna BottiVesna Botti depicts the Roma tradition of young marriage. For Vesna, marriage at 14 or 15 is an important part of Roma culture. She understands that from an outside perspective, early marriage may seem inhumane, but she was in love and happy to marry her husband (who was 15). |

|

|

|

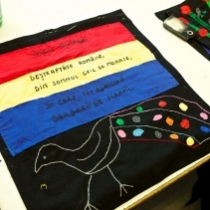

At the same time, she feels like she missed out on growing up and on a full childhood. Since the age of 14, Vesna has handled problems with her children’s health, marital difficulties, and conflicts with her parents-in-law. Vesna would like to see her own daughter, Chanella, break with tradition. She hopes that Chanella will finish her studies, find a job, and be independent. Vesna wants to stop begging and to have a stable job. She wants a to be part of a normal family, like anyone else in France. Vesna enjoyed working on the quilt. She wants to thank everyone involved and to say that the project was an important departure from her day-to-day life of begging. This panel, by Vesna Boti, depicts a poem by the Romanian poet Mihai Eminescu, named Somnoroase Pãsãrele (Drowsy Birds). Eminescu played an important part in Vesna’s childhood in Romania and she thinks of him with pride. Vesna’s father died when she was ten and her mother had no other option but to depend on social assistance and the support of friends and family. After her marriage at fourteen, Vesna left Romania to join her husband’s family in France. Vesna had her first child, Leonardo, when she was 15. Her daughter, Chanella, was born when she was 18. Today, in Strasbourg, Vesna begs to provide for her children.

|

Claudia BercutaClaudia Bercuta left Romania for a job in Germany in 1993. After another job in Spain, Claudia moved to France to be with family. Although life in France is better than life in Romania, Claudia had not found constant work in France at the time that she participated in the quilt project. |

|

|

|

In Strasbourg she begged to support her family. She lives in an isolated caravan with her six year old son, Ellis. Claudia’s panel shows the power dynamic between women and men in Roma culture. The man is heavy and powerful, while the woman is small and powerless. Claudia is intimately familiar with this inequality. She says that most Roma families face domestic violence or the threat of domestic violence. Claudia is divorced and raises her son as a single parent. She sets a good example for Ellis – no smoking or drinking- and teaches him to respect women. She had a great time working on the project and says that she is happy to have participated.

|

Ecaterina NedaEcaterina Neda’s family left Romania when she was six years old. Although she has few memories of her home country, she feels strong ties to Romanian culture, language, and history. For this panel, Ecaterina depicted the Romanian flag and the Romanian national anthem. |

|

|

|

Both give her a sense of nostalgia and pride. Although her family came to France for a better life, Ecaterina continues to face poverty. During the day, she begs in Strasbourg to provide for her four year-old daughter, Charlotte. This panel, by Ecaterina Neda, depicts the feelings that come from perpetual unemployment: “no papers, no work, not welcomed, but still hopeful.” Ecaterina’s family left Romania when she was six years old. Although she has few memories of her home country, she feels strong ties to Romanian culture, language, and history. Although her family came to France for a better life, Ecaterina continues to face poverty. During the day, she begs in Strasbourg to provide for her four year-old daughter, Charlotte. Ecaterina knows that a job would provide a better life for her daughter and improve her self-esteem and integration in France. This quilting project has given her an important professional experience and more confidence.

|

Mihaela MoldovanMihaela Moldovan joined the Roma community through marriage. Since her arrival in France, Mihaela has been expelled several times. She returns because she sees no future in Romania. Mihaela lives in a caravan with her husband and young son. They do not have electricity or running water. |

|

|

|

She lives under constant fear of the police coming to the caravan to expel her family or other members of the community. Not surprisingly, she finds this extremely stressful. Mihaela’s major hope is to see her son succeed in his studies in France. For Mihaela, this project is an important first step for her future. Her panel expresses the intense pain, violence, and loss that comes from endless expulsions. This panel, by Mihaela Moldovan, depicts a traditional Roma wedding, and portrays a moment of happiness, joy, and sharing in the community. Mihaela has included the phrase, Bine ai venit (“welcome!”) in her panel to represent the hospitality of the Roma culture. Mihaela joined the Roma community through marriage. Since her arrival in France, she has been expelled several times. She returns because she sees no future in Romania. Mihaela lives in a caravan with her husband and young son. They do not have electricity or running water. She lives under constant fear of the police coming to the caravan to expel her family or other members of the community. Not surprisingly, she finds this extremely stressful. Mihaela’s major hope is to see her son succeed in his studies in France. For Mihaela, this project is an important first step for her future.

|

Roxana NedaRoxana Neda has been in France for two years. She stopped studying in Romania, her home country, at the age of 14 and married at 15. Then she left Romania to be with her family and to find a better life. She wants to find a job and to ensure a hopeful future for her three children, Manuel, Melissa, and Pamela. |

|

|

|

Roxana is especially happy to see her children succeed in French schools with French children. Although she was happy to marry at 15, she wants her own daughters to finish their studies before marrying or starting a family. Roxana does not have access to running water or electricity in the caravan where she lives. Her husband helps with the children, but he has also faced difficulties with unemployment and immigration. Above all else, Roxana wants to leave her life of begging behind. Her hope is to have a simple, decent, and integrated life in France. For her, this project represents an excellent beginning and a hope that she will have more opportunities to fully integrate into French life. Roxana worked on making the central (Dosta!) panel in the quilt. The quilt project and the campaign give her hope for the future of the Roma people.

|

|

She does not have electricity or running water and she begs for money to support her family. Her goal is to find a steady job and to provide a better future for her young son. Dominica’s panel depicts the separation of Roma children from other children in Romanian schools. The faces in her panel express the sadness, shame, and anger associated with segregation. Dominica wants to stay in France to ensure that her son has an education like any other French child. This project was especially important for Dominica and she would like to thank the Council of Europe. This panel depicts a married couple harvesting apples. It hearkens back to the time that the artist, Dominica Nicola worked in agriculture with her husband in Romania. Twenty years ago, she suffered from a life-threatening liver illness. When her family could not afford the necessary treatment, Dominica moved to France for medical care. Today, she lives in a caravan near Strasbourg. She does not have electricity or running water and she begs for money to support her family. Her goal is to find a steady job and to provide a better future for her young son. Dominica’s panel depicts the separation of Roma children from other children in Romanian schools. The faces in her panel express the sadness, shame, and anger associated with segregation. Dominica wants to stay in France to ensure that her son has an education like any other French child. This project was especially important for Dominica and she would like to thank the Council of Europe.

|

|

Ramona’s panel depicts the pain of forced expulsions. It also expresses her constant fear that police may arrest her for begging and confiscate the cash that she has collected during so many hours of begging. When she has negative interactions with the police, she feels intense shame at having to return to the caravan without money or food for her children. She is very happy to have participated in this quilt. It represents a new opportunity, a new beginning, and new hope. She would like to thank everyone who worked on the project.

|

| She has no other option but to ask for money in the streets or at churches. For Florea, begging is extremely fatiguing, depressing, and dehumanizing. The quilt project is the first regular job she has had since her arrival in France. She hopes it will lead to additional opportunities to improve her and her family’s lives. |

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

|

The quilt will be exhibited at the Roma Pavilion until October. The Council of Europe is the foremost international agency working on Roma rights. It has launched a campaign against Roma discrimination, Dosta! which is depicted in the quilt. Robert Palmer, director of the Council’s Directorate of Culture and Cultural and Natural Heritage was one of the opening speakers at the Roma Pavilion.

“Those people who are nomadic…have to find different ways of understanding themselves in the world” – Salman Rushdie Below left: The Roma quilters present their quilt to Deputy Secretary-General Maud de Boer-Buquicchio at the Council of Europe. Left to right: Roxana Neda, Vesna Boti, Dominica Nicola, Ecaterina Neda, Maud de Boer-Buquicchio, Ramona Stancu, Florea Neda, Mihela Moldovan. |