Maasai Quilts

Background

Background

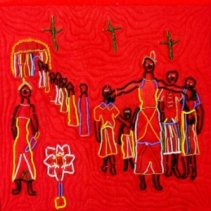

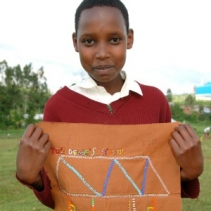

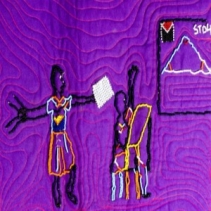

The Idea is Born: Peace Fellow Charlotte Boudillon discusses quilting with the Rehema widows. AP has partnered with the Kakenya Centre for Excellence in western Kenya to produce the Rehema Widows Quilt and the Maasai Girls Quilt. These spectacular two quilts are made with beads and a scarlet backing, in the Maasai tradition. The quilting began in the summer of 2011. Peace Fellow Charlotte Bourdillon had been working at Enoosaen for most of the year. In the summer, she was joined by Cleia Noia. The original idea had been to work with girls from the school, but Kakenya’s mother (“Mama Kakenya”) suggested that working with widows as well would give a more rounded picture of the life of women and girls. She introduced them to some of her friends, known as the Rehema group. (Rehema means “compassion in Swahili). The two Fellows used their computers to bring up photos of other advocacy quilts from Bosnia and the DRC, and explained the concept of advocacy quilting. They then invited the women to tell their own story through embroidery. The women responded enthusiastically. Mama Kakenya is a committed foe of genital cutting as are all of the Rehema widows, so it was perhaps not surprising that they chose to depict what they had gone through. Several of their designs are not for the squeamish. Like other Peace Fellows who have supervised the making of quilts, Charlotte and Celia were thoroughly absorbed by the whole process and by the communal nature of the sewing. Cleia described the process in a blog, Stories Worth Telling. They began by asking the women to describe their experience and what they wanted to design. They then asked two local artists to help sketch out the initial designs, but found them uninterested so Charlotte put pencil to cloth and mapped out some rough designs. Cleia continued: “We later distributed these drawings to the women, and gave them all the material (beads in different colors, strings, and needles) necessary to start the beading. They are very excited about the project, and some are almost done with their first panels. After seeing the work done by their fellow group members, other women who were not initially participating are now eager to join our project, and Charlotte has already collected new stories to draw.”  Kathy Springer headed the group of quilters who assembled the Rehema Widows Quilt in Indianapolis. Parallel to this, Charlotte and Cleia also worked with a group of sixth graders at Kakenya’s school to produce blocks for a separate quilt, on the value of education. The mood of these young artists – who had escaped genital cutting when they enrolled in the school – was considerably lighter. They wanted to use their panels to express their dreams for the future. Charlotte and Cleia reserved some time after school, and invited a local beading expert, Parako, to come and give instructions. As Charlotte wrote in a blog, this helped to instill a respect for Maasai traditions in the girls: “Only around 20% of the girls had been taught how to create traditional beadwork by their mothers or grandmothers. Again, Kakenya works to emphasize positive aspects of Maasai culture while also educating about the harmful aspects.” The girls needed no incentive to produce their beaded panels. As Charlotte wrote: “ (They) love having a craft to work on during their free time. I keep finding them in the classroom working on their projects during lunch!” The process produced some delightful vignettes. Peyiai was one of two girls who wanted to be a helicopter pilot. Gladys (photo) said that she wanted to build a school for handicapped children when she grew up. Brenda depicted herself at the computer, learning new things from the Internet. Like the widows, the girls relished the opportunity to tell their stories through art. Their message was certainly a lot lighter. Charlotte returned to the United States with both sets of blocks to begin the process of assembling the two quilts. She approached her mother’s quilting guild in Indianapolis. Four quilters – Charlotte’s mother Sarah, Jane Lee, Cathy Banks, and Kathleen Springer – agreed to participate. Charlotte then found another expert quilter in New Jersey, Onalie Gagliano, who agreed to take on the Maasai Girls Quilt. Onalie has a deep affection for Kakenya, and has twice visited the school with her own daughters. She was particularly taken by the humorous images.  Center of Attention: The Maasai Girls Quilt on display at the UN in New York, March 2012. The quilters worked together by phone and email to make their designs as compatible as possible, and their two quilts were shown for the first time at the United Nations exhibition on March 8, 2012, where they drew praise (pictured left). The quilts were then shown at Kean University between January and September 2013. The Rehema Widows Quilt will be shown next at the textile Museum in Washington. One of those present at the UN on March 8 was Megan Orr, who visited the show shortly before leaving for Kenya to work at Enoosaen as a Peace Fellow. Megan herself loved the quilts, and one of the first things she did on arriving in Enoosaen was bring up the photos on her laptop. As she later wrote in a blog, the girls expressed little interest because they did not know what the UN was. But they went wide-eyed with fascination when Megan brought up the photos of their own panels and showed them the finished quilt, so beautifully arranged by Onalie. It helped Megan to understand the empowering impact of technology: “These girls were fascinated and completely plugged into the reality that they were on the Internet.” This was one of the few times that AP has been able to return and reconnect artists with the quilts they had helped to make. It will not be the last. |

Maasai Girls

Maasai Girls

|

|

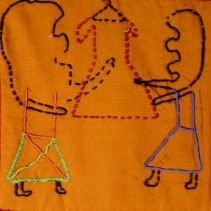

Lynn Lynn is one of 7 orphans at Kakenya Center. Her panel represents her dream to grow up and be able to help other needy children. In the picture, she is giving a dress to an orphan. |

|

|

|

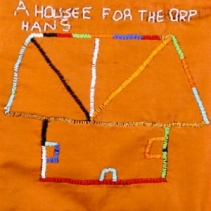

Napukenya While Maasai have traditionally lived in manyatta homes, education will free Napukenya to live in a concrete house and build a better life for herself than her grandparents could. |

|

|

|

Nasieku “My picture is about helping the needy,” says Nasieku. “It is so wonderful to help the needy.” |

|

|

|

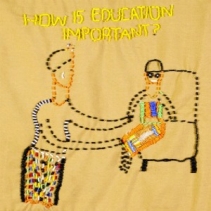

Faith Faith says, “Education is important because it allows us to read and write and spell, even though many Maasai people are not given this chance.” Her panel shows the school she dreams of building. |

|

|

|

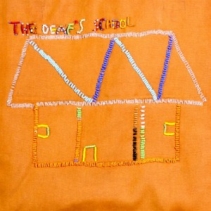

Gladys Gladys’ dream is to become a doctor and to build a special school for the blind. The house in her panel is what she hopes this school will look like. |

|

|

|

Sharon Sharon’s panel depicts her dream of becoming a surgeon. “I thank God for giving me an interesting dream,”she says. |

|

|

|

Jackeline Jackeline’s dream is to become a lawyer. “Some girls drop out of school because of being pregnant or orphans. Every child has a right to education, and we should help them,” she says. |

|

|

|

Vivian Vivian wants to study hard so that she will not have to dig and work hard as a farmer. Instead, her dream for the future is to become a pilot. |

|

|

|

Peyiai Peyiai dreams of becoming a pilot because she believes that she will be able to help the needy and the poor. Her panel shows her flying an airplane. |

|

|

|

Naomi Naomi’s panel represents her dream of building a hospital in her community and becoming a surgeon. “I wrote a heading saying ‘health for everybody,’” she says.“That is why I want to be a doctor in the future.” |

|

|

|

Lyn Lyn says, “I drew about how I will use my education in the future when I get knowledge and grow up.” She depicted an airplane flying to North and South America and says she will become an optician in the United States. |

|

|

|

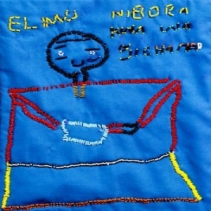

Nenkoitoi Nenkoitoi’s picture shows a small girl in a wheelchair who is an orphan. When she grows up, she wants to be a doctor and use her salary to build houses for the blind, disabled, and deaf. |

|

|

|

Juliet Juliet’s panel shows her dream of using her education to build a beautiful house for her parents, including a new farm and cows. |

|

|

|

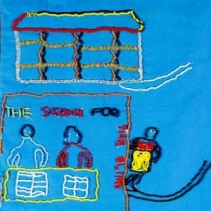

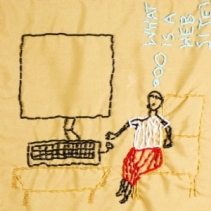

Brenda Brenda’s panel shows someone using a computer. She says that it represents how a person can acquire education and how this allows them to have knowledge and skills needed to operate technology. |

|

|

|

Shura “My picture is about when I grow up and build our nation,” says Shura. She dreams of becoming a nurse and of helping children with special needs. |

|

|

|

Kakenya “In the future,” says Kakenya, “I have a dream that I would like to advise and teach Kenyans why it is important to educate girls.” Her panel is about girls who are denied education. |

|

|

Rehema Widows

Rehema Widows

|

|

Naori Naori’s picture shows the plight of all Maasai women, having to lug materials and build their home, while the men sit and watch them, yelling and beating the women at their leisure. |

|

|

|

Ann Ann’s panel is about how she spent her life working very hard to earn money for her children’s school fees, selling what little Ann’s second panel shows how, if she is not forced to remarry one of her dead husband’s relatives, a widow will be forced to leave the family farmstead and all that she has worked for. She is left with nothing. |

|

|

|

Anonymous This panel is about a woman who was forced to marry a much older man as his second wife, and she recalls the pain of having been pregnant and already with one child at age 14 or 15. Artist photo unavailable. |

|

|

|

Sarah Sarah says, “I had so many challenges because I was very unhappy when [my] husband passed away… life was very hard for me, so I went to ask for help from my in-laws but was rejected. I had no money for food or school fees for my 7 children.” |

|

|

|

Nairikungera Nairikungera’s panel shows another struggle women face: her family’s mud hut burns down, and since it is considered below a man’s status to touch the dung used to rebuild it, she must reconstruct it all herself. |

|

|

|

Parakwo Parakwo’s panel is very explicit. It shows the fear in the girl’s face as she is circumcised. |

|

|

|

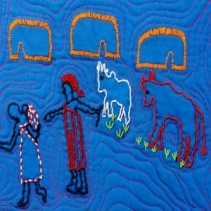

Eunice Eunice’s panel shows a grouping of traditional Maasai houses, or manyatta, where special ceremonies are held. The widows are forced to stay separated from the rest and face discrimination from the rest of the community. |

|

|

|

Rose Rose’s (photo unavailable) panel is about a girl who desperately wanted to stay in school with the boys but was dragged forcibly out of school when she was to begin grade 4. |

|

|

|

Nairekumurran Nairekumurran’s panel shows a man threatening a woman with a knife. She says that she wants all who see it to know that this kind of violence is one of many challenges that women face. |

|

|

|

Noonkipa Noonkipa’s panel depicts a girl who has just given birth. The women around her have decided that since she was not circumcised before as they think she should be, they will forcibly circumcise her while she is unable to resist. |

|

|

|

Josephine When Josephine’s husband died, she refused to marry her brother-in-law. Her panel shows the consequences of this decision: a woman is crying because her in-laws are rejecting her and her young child. |

|

|