Vietnam Disability Quilt

Background

Background

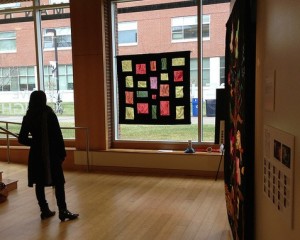

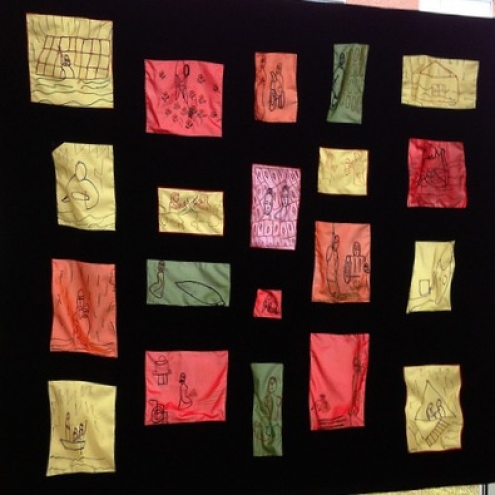

Climate change and disability: Cao Thi Men, a survivor of the Vietnam War, produced several squares for the Vietnam Disability Quilt that warn of the impact of climate change and flooding on people with disability. The squares for this quilt were embroidered onto chiffon and silk cloth in 2012 by Cao Thi Men and Long Ngru, two Vietnamese women who overcame devastating injuries to become skilled craftswomen. They worked under the auspices of the Association for the Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities (AEPD), an AP partner based in Quang Binh province, Vietnam. Jesse Cottrell, who served at AEPD as a Peace Fellow in 2012, oversaw the quilting project. It began when AP asked Jesse to explore the possibilities of making a quilt during his training in Washington. When he arrived in Vietnam, Jesse put out feelers among AEPD’s members and was given the names of Ms Cao and Ms Long. Cao Thi Men was six when a bomb blast shattered her spine during the Vietnam War. She was bedridden for thirty years before an outreach worker from the AEPD persuaded her to visit the hospital. A doctor removed the shrapnel, and her life began to change. Two years later, she started to attend AEPD meetings. With Hun’s help, she secured a job weaving conical hats with the local women’s union, the first job of her life. Ms. Cao also made her first friends. Most were also persons with a disability who had also dealt with depression and social exclusion. Jesse met Ms Cao and asked if she wanted to participate in the quilting project. He later explained in a blog: “Ms. Cao quickly said yes. I didn’t need to explain how other PWDs could benefit from hearing her story. She understood that quilting was a way for her to comfort others, just as Mr. Hun had helped her. “‘Sorry, I could only make 12 (panels),’ Ms. Cao told me when I came to her house to pick up her panels for the quilt. I hadn’t asked for more than one or two. Instead, Ms. Cao had singlehandedly made enough panels to make a whole quilt!” The squares in the quilt tell the story of Ms Cao’s life. Most are grim. One shows a mangled body. Another shows a frowning, legless woman next to a bomb. In other panels, Ms Cao recalls her experience during the 2009 floods and makes a larger point about the likely impact of climate change on persons with disabilities. One tile depicts a PWD trapped on the roof as a flood engulfs her home below. Another tile shows a PWD carrying her dog on her head, above the water.  Long Ngru was one of two Vietnamese artists who produced squares for the Vietnam Disability Quilt. The second quilter, Long Ngru, was 19 when she was hit by a motorbike and crippled for life. She spent the next 13 years of her life in a wheelchair, often depressed. According to Ms. Long, this changed after she was introduced to AEPD. Ms Long attended a training at AEPD and discovered a supportive community of other PWDs who were also trying to deal with depression and social exclusion. After another training she received a grant from AEPD that paid for a refrigerator and helped her to open a cafe. Ms. Long also met her future husband – another person with a disability – at the training. The two were was married a year later and now run the cafe together while raising their first child. Ms. Long’s told Jesse that she wanted her quilt squares to express the happiness she felt after AEPD helped her to meet other PWDs and start a family. Ms Cao also wanted to convey optimism and social inclusion. “This one shows that disabled people can be useful in society,” she said, displaying a panel of a crippled person farming. “And this other one shows me making conical hats for a living.” She smiled as she said this. Ms. Cao is happy with her new life. After Jesse brought the embroidered squares back to the US, they were assembled by AP’s Program Manager Karin Orr, Karin’s aunt Teresa Orr, and Nancy Evans from the Faithful Circle Quilting Guild in Columbia, Maryland. The quilt was exhibited for the first time in January 2013 at Kean University, where it hung against a window. This allowed sunlight to pour through the fabric and bring out the strong message behind this exquisite piece of art. The quilt was again shown in November 2013 at the Textile Museum display in Washington, where it stood in the entrance.  On Display: The Quilt has been displayed at several exhibitions in the US. It hung for nine months at the Kean University Human Rights Gallery.  Reading about the Vietnam Disability Quilt. |

Quilt

Quilt

|

|

|

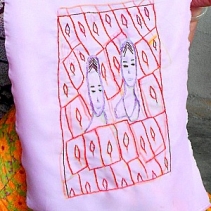

Cao Thi Men A PWD waves for help from her roof during a flood. |

|

|

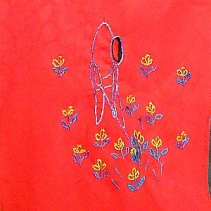

Cao Thi Men A PWD tends to a bed of roses. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men A PWD plays the guitar for an able-bodied person. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men An amputee organizes agricultural products, proving that PWDs can contribute to society. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men A person holds the family dog over her head during a flood. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men A PWD seeks shelter on her roof during major flooding. |

|

|

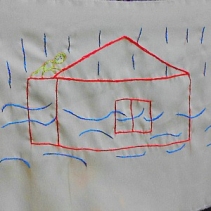

Long Ngru A scene in which a PWD lives through major flooding. |

|

|

Long Ngru Long Ngru depicts herself in a wheelchair sewing baby clothes for her daughter. Her husband is also a PWD. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men PWDs sit on their roofs during a flood. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men A PWD in an agricultural community. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men Ms. Cao depicts herself next to the missile that hit and crippled her. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men An able- bodied person helps someone in a wheelchair. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men PWDs in a major flood. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men Ms. Cao depicts a PWD farming, to prove that PWDs can be useful in society. |

|

|

Cao Thi Men A person with disabilities. |

|

Cao Thi Men A PWD working on a farm. |

Poster

Artists

Artists

Cao Thi Men

Profile by 2012 Peace Fellow Jesse Cottrell In 1973, six year old Cao Thi Men and her little sister were Shrapnel from the bomb had cut Ms. Cao’s spinal cord and was embedded in her lower back, leaving her in agony. Surgeons couldn’t extract the shrapnel without risking her life. “I considered suicide,” Ms. Cao told me. When Mr. Hun, an outreach worker from the AEPD first visited Ms Cao in 2007, she had already spent more than three decades confined to bed and was very depressed. But Hun, who himself has a disability, persisted. It took two years, but Ms Cao finally agreed to seek medical help. Surgeons were able to removed the shrapnel from her spine. The change was dramatic. The pain was gone and although Ms Cao couldn’t walk, she regained enough movement in her legs to leave her bed without assistance for the first time since she was a child. It took another two years for Mr. Hun to convince Ms. Cao to attend her first AEPD training, in basket weaving. She was a natural. With Hun’s help, she secured a job weaving conical hats with the local women’s union, the first job of her life. Ms. Cao also made her first friends, most of them PWDs who had also dealt with depression and social exclusion. When I asked her if she wanted to participate in the AP quilting project, Ms. Cao quickly said yes. I didn’t need to explain how other PWDs could benefit from hearing her story. She understood that quilting was a way for her to comfort others, just as Mr. Hun had helped her. “Sorry, I could only make 12 (panels),” Ms. Cao told me when I came to her house to pick up her panels for the quilt. I hadn’t asked for more than one or two. Instead, Ms. Cao had single-handedly made enough panels to make a whole quilt! It was also apparent that she had sewn her life story. One panel shows a mangled body. Another shows a frowning, legless woman next to a bomb.

Yet another depicts a PWD trapped on the roof as a flood engulfs her home below, as almost happened to Ms. Cao during Vietnam’s historic floods in 2010. This underscores the challenge that will face many PWDs from climate change – and this theme is apparent in many of the quilt panels. Yet, amidst the stories of struggle and sorrow, Ms. Cao’s panels are of optimism and social inclusion. “This one shows that disabled people can be useful in society,” she said, displaying a panel of a crippled person farming. “And this other one shows me making conical hats for a living.” She smiled as she said this. Ms. Cao is happy with her new life. She laughs when she plays with her nieces. She smiles with pride when she shows visitors her beautiful woven bowls. It was only when I asked Ms. Cao what she thought of AEPD and Mr. Hun that the look on her face changed, hinting at pain she’d only recently overcome. “They gave me my life back,” she told me, with tears in her eyes. “I owe them everything.”

Long Ngru

|

playing in a field when they heard the screech of an incoming American plane. Instinctively the young Cao Thi Men wrapped herself over her younger sibling. Her first memory after regaining consciousness is of her baby sister, screaming but unharmed. Her next memory is trying in vain to move her legs.

playing in a field when they heard the screech of an incoming American plane. Instinctively the young Cao Thi Men wrapped herself over her younger sibling. Her first memory after regaining consciousness is of her baby sister, screaming but unharmed. Her next memory is trying in vain to move her legs.