My tasks at Umoja sound simple. Rebecca is going to Sante Fe in July to sell Umoja’s jewelry at an exclusive crafts fair; she will also go to Washington, DC, to have a market fair at the Vital Voices office. In preparation for her trip, I am to photograph each piece of jewelry, create a product catalog with all of the items that lists the measurements (weight, size) of each piece, a compelling story about the necklace or bracelet’s origins, and come up with names for each one. I will interview two women who have participated in training workshops with Vital Voices at the village, and tell the story of their lives – before and after Umoja. And, I will create a shortened version of the product catalog that has the ex-works price (labor costs + materials + +overhead + 15% profit margin) listed for each item so buyers can know how much each item costs and how many can be made per month. It’s simply a matter of collect the data and reporting it, yes? No, actually. “Yes” assumes there is a system, a method for gathering information, for recording it in village books. It is natural, for me (Westerner) to assume this information would be available, I just have to ask for it.

So I asked Rebecca, how much do you spend on beads per month? And she pauses, eyes widening – Per month? Oh, she looks down, then to the women beading around her. I have no idea, she shrugs. I break it down: where do you buy the beads? She replies: Nairobi, sometimes here at Archer’s Post, where the price is double. Me: Okay, how many times do you go to Nairobi to buy beads, and about how many do you buy each time? Rebecca: (thinking) I go maybe three times a month – no, two times – it depends. And when I go, I get what we need; that changes. Me: And how much are the beads in Nairobi? Rebecca: Some colors are one price, other colors are more expensive. Me, talking to you: this is not simple.

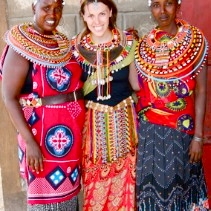

Photo: Kate Cummings, Umoja Uaso. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009. Kenya

Photo: Kate Cummings, Umoja Uaso. Partner: Vital Voices, 2009. Kenya

The systems We have in the West – rote, boring, established – are not here, in the desert, in northern Kenya, with women who have not gone through Our systems and cannot automatically spit out what We want. I am proud of them, actually, for functioning without Our systems (I’m including you in this, forgive me but We are responsible), but in order for them to receive a fair price for their beautiful jewelry through Our outlet, Umoja has to develop these cogs in the system: minimum wage, hours worked for each item, materials used for each item, and how much the community spends per month on the whole production, the business. The weight of this task felt like an anvil on my chest when I finally saw the enormity of what I was supposed to do in, now, 5 days. So we start (there is no time for waiting, in this sun, in this role of responsibility).

Rebecca, we are going to have to time five women – your fastest and most skilled beaders – making five different products, your most popular (I wait for resistance. None; I continue). I will have to sit with them from the moment they begin making the jewelry to the second they finish, timing all breaks taken (still no complaint). I will have to weigh every bead, piece of plastic, rubber and string used – before they finish and after. Someone will have to take care of their children; it could take days. –And Rebecca, what does she say?—You come tomorrow, at 8 in the morning, and we will begin.

And when I come at 8am, they are there, waiting for me under the acacia tree. They are seated (with natural elegance) on the cowskin rug, each of them assigned to one of five pieces. Systems! Who needs a system when there is such diligence and commitment? I know, diligence can benefit from structure. What I mean is: too bad we do not find this diligence, this willingness and openness, throughout the systems We have – a trust in the possibility for improving one’s habits because, simply, maybe there is room for positive change. It is complicated – my head already wants to return to the commitment under the acacia. And we will, when I can settle the sandstorms that have swept from outside my hut into my head – I am still adjusting to the role of system-starter, of translating the pace of Samburu into the international marketplace.

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Jul 2nd, 2009