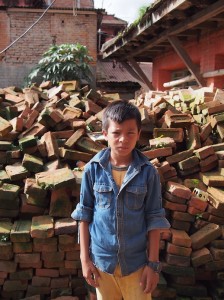

Muskan Tamang, looking very serious for a 13 year old girl. Her mom works a carpet factory in the off season and the brick factory in the dry season. Her dad has been gone for the past year, to work in Bahrain. She aspires to be a nurse.

Tuesday was a long day of interviews which started with an extra long bus ride from Kathmandu to Bhaktapur. Our first interview of the day was with Muskan Tamang. She gave the impression of a quiet and serious young girl. Eventually it became apparent that most students 12 or older tended to have a more serious attitude given that as they transitioned into their teenage years their families seemed to expect more of them as well. This transition from childhood to adulthood is something we all expect, but the timing can vary greatly between countries or economic circumstances. In the United States, childhood seems to last longer and longer, for better or worse. Sociologists have in fact created a new term to define the extra time adults in the United States seem to need to actually become independent, functioning members of society. They call this period “emerging adulthood” and it generally occurs in the late teens through the twenties. For me this is such a stark contrast to the pre-teens I’ve interviewed who are already expected to take on adult work in their families.

This expectation makes it especially difficult for the students to avoid assisting their families in the brick kiln, even when CONCERN-Nepal is funding their education. Some students still work in the kilns to varying degrees. In most instances it is not more than an hour or two, but there are rare students who are expected to do much more, like Bishal Manandhar.

Bishal is 13 years old and from Ramechhap, a rural area to the southeast of Kathmandu. Although he has only spent 6 months in the kilns, compared to some children who have already worked as many as 6 years in the kilns, he had one of the most grueling schedules of any of the children we’ve interview and had suffered additional hardship on top of that. Last dry season he would wake up at midnight and begin making bricks. He would make bricks until 9 am and then he would go to school. After school he would work for another hour or two. His parents, who are both illiterate made the decision to work in the kilns after their home was destroyed in the earthquake. While working at the kilns he was injured and received no compensation or medical attention.

Bishal worked 10 hours a day while the brick factories were open. Being able to attend school under the circumstances was at best a mixed blessing. While staying in school will give him a better chance at finding work outside the kilns later, adult expectations weigh heavy on Bishal and its obvious that this kind of hard labor is taking its toll.

In contrast to Muskan and Bishal are Alina and Yamsay Tamang, who are only nine and seven years old respectively. Below is a video of them taken by staff at CONCERN-Nepal, happily flipping bricks as if its just another game for them.

In the interview, they boasted of their expert skills in brick flipping. During the interviews they were all smiles as they talked about their life in Bhaktapur. Even with the difficult circumstances the younger brother Yamsay is top of his class and even helps his sister study since their parents are illiterate and unable to help. For now they are young and things are still easy compared to Bishal’s daily life, but how many more years until they face the same difficulties? When will their childhood abruptly change to adulthood?

Posted By Lauren Purnell

Posted Jul 17th, 2016

263 Comments

Laura Stateler

July 18, 2016

I loved the video you attached with this blog. The stories and hardships that these young kids face is very sad, but seeing a video of them still with a youthful nature was good! You do a great job of being informative while bringing humanity and a spirit to the people who you are meeting!

Rachael Hughen

July 19, 2016

Its so strange to see the kids laughing and joking around while working in a brick kiln, something that our country considers a huge human rights violation. These kids seem so strong and resilient that no matter what conditions they seem to be put through, they still act like kids! However, makes me think about how this type of work will affect their education, health, etc. in the long run. Heartbreaking to see that once they reach pre- teen age they grow up so fast… do you think that by removing these children from a life of hard labour and placing them in school full time they will regain some of their youth, or is this early mental maturation permanent?