Dave Matthew’s “Don’t drink the water” was the first thing that started playing in my mind as Mr. Xoan explained how he was exposed to Agent Orange. ‘I drank it thinking it came from the rain’, he said. Instead the H2O source was a river exposed to the defoliant.; a river that carried tragedy and the legacy of war through its current.

The family began having children soon after, and out of the 5 children they had 3 of them experienced complications from the exposure, 1 died of a miscarriage and 2 of them were born healthy and later went on to marry; their photos proudly hang on the family’s wall.

The first child born with AO complications was Trung, born in ’79. He had a normal childhood until one day his legs started failing and the arcs on his feet went through a malformation that doesn’t allow him to walk properly and restricts his mobility. As we showed up with Tuan, the outreach worker that oversees Mr. Xoan’s case, Trung began to show us pictures of his father’s visits to the graves of his friends who fought during the war but didn’t make it home.

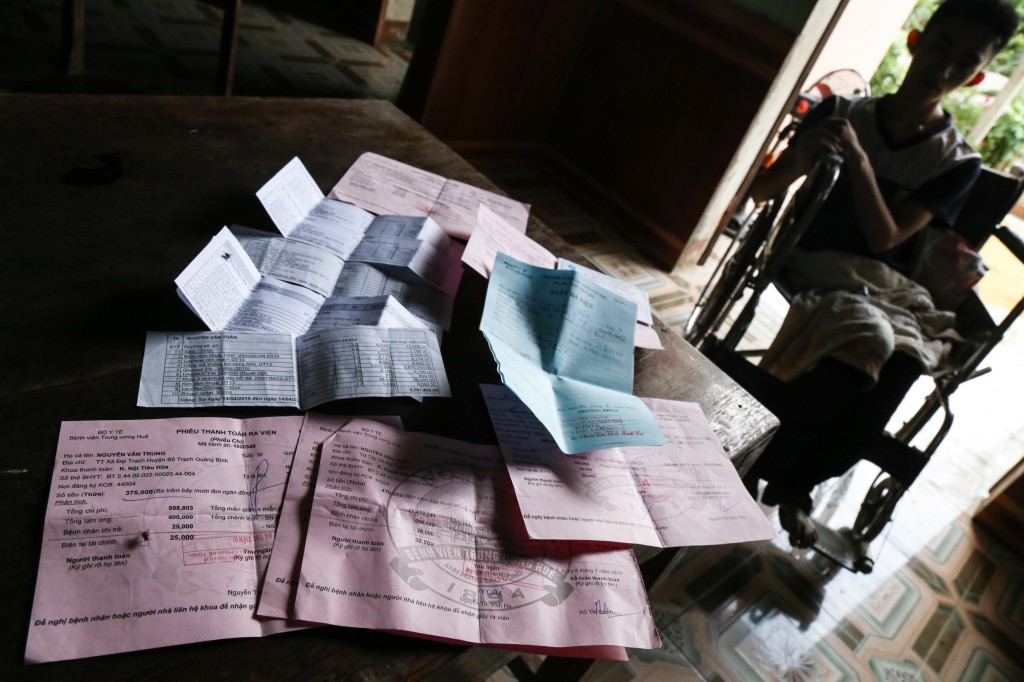

Toan, born in ’95, suffers from similar complications than his brother and a more severe case of malformations on his legs. For a while he tried to walk, but as his legs continued degenerating his classmates began to make fun of him which left his parents with no other choice but to take him out of school. A few months passed and the doctor informed them that a wheelchair would be needed for the rest of his life, if he ever wanted to move around. Both him and his brother not only share similar diagnosis but hemophilia as an added burden in their lives.

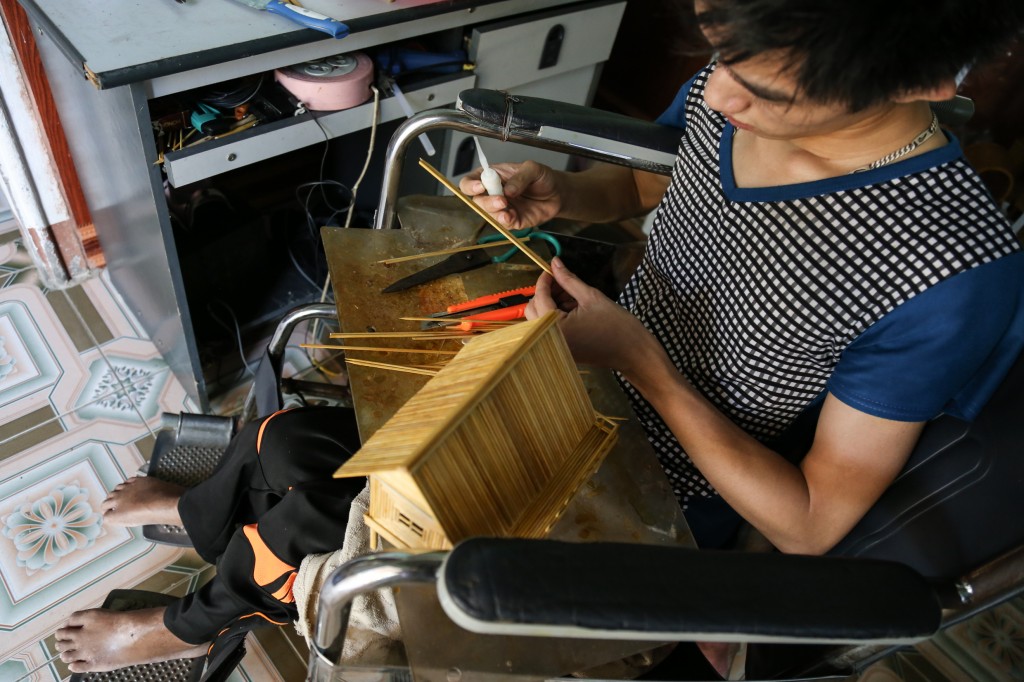

Toan could have so much to complain about, yet shows so little resentment and instead is trying to become a productive young man. The first things you notice as you walk into his house is this sort of artist’s studio with chopsticks, glue, varnish and others spread neatly on top of a table. Toan has been fortunate enough to have found a mentor of sorts in one of the people that go to his self-support group. Encouraged by Toan’s positive attitude, his mentor taught him how to make handicrafts out of simple items that he buys for him at the local market. The results are remarkable, yet Toan’s dreams don’t end there. “I wan’t to learn how to develop webpages so that I can work from home”, he tells me, a goal that is currently only limited by the lack of a computer and internet connection. However, Toan doesn’t see that as very far from becoming a reality. “I’m already reading about it from books I get from the market”, he added.

Last came Lien, born in ’92 with cerebral palsy. We met her (on a soon-to-be stormy day) laying in bed, pressing her nails against her hands and grinding her teeth, as a sign that ‘the weather was about to change’, said her mother. At times, she presses her nails so hard against her hands that they end up cutting her palms and drying them out. Given this, her parents give her folded carton to hold in her hands to protect her from further cutting.

‘It is a full time job, 24 hours of the day are invested in taking care of Lien; she constantly needs for one of us to help her’, says her mother, Phan Thi Do.

As we went around meeting the different families suffering from the effects of Agent Orange (AO) exposure, a clear pattern began to appear -one of the mother as the main caregiver. It wasn’t that the father was absent, it was just that the mother’s dedication and willingness to sacrifice for her children who suffered the most was extraordinary.

I entered Lien’s room and her mother welcomed me with a smile, while she continued wiping her daughter’s face with a damp cloth. Soon after, Mr. Xoan silently peeked into the room and IMG_3042 was made. I couldn’t help but to shed a tear as I looked at my DSLR display and noticed how the photo told the story of so many families exposed to AO; a story of thousands of mothers taking the huge responsibility of caring after their children while the father figure sheepishly looked from afar.

Moreover, in one of the many visits to Mr. Xoan’s family we found to our surprise that neither him nor Toan or Trung were around. ‘They went to Hue for their hemophiliac monthly treatment’, Mrs. Phan said. The treatment costs 6 million vnd (270.6 usd), an amount that their insurance covers at 80%. In the end, the fact that all men were unexpectedly gone turned out to be a blessing in disguise, as were able to witness the close connection that can only be present between a mother and her daughter.

For the next 5 hours we bore witnesses to how important Mrs. Phan has become to her daughter Lien, who caresses her mother’s arms and lays on her shoulder every time she can. That gesture could be interpreted as Lien’s demonstrating her affection and gratitude for the sacrifice her mother makes day by day.

As I continued to look for details that will help tell Mrs. Phan’s family story, I notice a photo laying next to the kitchen but not hanging on the wall. The photo showed several discrepancies from the way her children actually looked, specifically the straight and tall posture that all of them exerted, so I inquired about it. ‘A friend of mine took our faces from different photos and photoshopped them to the bodies’, I was told.

Perhaps this was the way Mr. Xoan and Mrs. Phan want to remember their family: healthy, looking good and with no sign of that damn herbicide that changed their lives forever.

Posted By Armando Gallardo (Vietnam)

Posted Sep 9th, 2015