Walking into town with Kakenya is an event. Old women stop her every ten feet, touching her head to remind her that she is still the child and they are her elders. “She is my mother,” Kakenya whispers – and after she has said this a dozen times, we come to learn that in this village, raising a child is indeed a communal effort. Older men, carrying their smoothed sticks with metal club-heads (a symbol of power among the Maasai) reach for Kakenya’s braided crown: “taqwenya” they say and she replies, facing the ground, “igo.” The children stand on the edges of the red path, giggling; some of the brave ones run up to Kakenya and remind her who they were last year, or the one before, when they were even smaller. “It is you? No!” Kakenya yells, laughing as soon as she realizes the adolescent is not the five year-old she remembers.

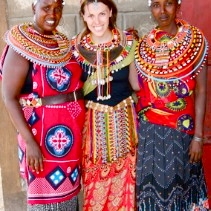

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Enoosaen, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

Photo: Kate Cummings. Location: Enoosaen, Kenya. Partner: Vital Voices

And there are some people she has to pass by, just to make it to the town center before the day is through. “You see that man? He was my fifth grade teacher. And him? Oooh, I dated him for awhile. Yes! I know, he looks older; the alcohol they drink here, it turns your skin so quickly.” And so we move down the impromptu line of greeters, each one shouting a hello to the American woman who was once just another child in this town. Lately we have been catching motorbikes from the farm instead of walking the 45 minutes to town, giving Kakenya a moment’s peace. Nearly everyone Kakenya has ever sat next to in class, gone on a date with, sold milk alongside, greets her from the earthen curbs of Enoosaen – and not all of them want to welcome her home.

Meetings in town start late and run even later, and as the hours wear on Kakenya slumps further down in her chair. There are board meetings for her school; gatherings with mentors and mentees of the youth mentoring program she is managing; hours spent with village elders who offer to quell tensions between Kakenya and members of the community who take advantage of her projects funds when she is away. After meetings, some people lag behind, looking for a moment with Kakenya. She sighs as she makes her way out of the room, always the last to leave – “did you see that man talking to me? He wants me to send his girl to the US. What does he think I can do? I’m just a student, too.” These interactions are the most exhausting for Kakenya – and they happen at the tailor’s, outside the store, while we are waiting for a car to go home. Unlike appeals from strangers in Nairobi, these requests cannot simply be ignored; Kakenya is the child of a village that is collectively responsible for her education in the US.

Kakenya is determined to return to Kenya with her husband and son as soon as possible, and this means she will be visiting her hometown more regularly. In short, her family is still here, her projects are here – she cannot push aside the requests of her extended Enoosaen family. And when difficulties arise with board members and other participants in her projects, Kakenya cannot simply replace these challenging people; they are her relatives, her neighbors – and, as they remind her, they are the ones who enabled her to start her life in the West. With the groundbreaking of her school behind her and the students now sitting in classrooms, Kakenya is faced with the complications of a dream coming true, in a town that both hungers for opportunity and starves its own chances for a different future. There is a saying in Asian cultures – “the finger pointing at the moon is not the moon.” Kakenya, despite her talents and profound generosity, is not the moon – nor is she supposed to be. She is doing her best to point out the true source of this community’s wealth (for one, it’s girls), and one too many minds clouded by desire and acquisition see Kakenya, fresh off the plane, as their single portal to a different life.

Posted By Kate Cummings

Posted Aug 5th, 2009