This series of blog posts tells the stories of the people affected by chhaupadi, with a view to explore different aspects of the practice in depth. All testimony and photographs in this series have been made available with the relevant subject’s express consent. A general introduction to chhaupadi is available here and there are more photographs in this album.

14 year-old Sunita Dhugana’s favorite subject at school is math. It might be her deductive mind that makes her the perfect candidate for the first post in this blog series—she gives answers to interview questions that comprehensively cover the practical components of the chhaupadi custom. Sunita uses her experiences to reveal how the cultural prescriptions of menstrual banishment play out in practice, citing fact after fact to illustrate her story in a concrete way.

Sunita Dhungana with Tulasi Kadel standing behind her

“[My family’s] chhau goth has no doors, no window, no lock; it doesn’t feel safe…but at least it has a bed frame”, she says, referring to the hut that was constructed to house all of the female members of her family during their menstrual period. Sunita explains matter-of-factly how it all happens.

A chhau goth (not the one used by Sunita’s family). The dishes in this photograph are used by women and girls only when they are menstruating, and may not be touched by other family members.

Every month, when her time comes, she moves into the chhau goth for four days. She sleeps there and, when she wakes in the mornings, is brought some food by her mother. The food comes on a separate plate that is used only during these four days each month; there are also designated chhaupadi utensils that are segregated in the same way. Sunita has to wash these utensils and plate herself, in a separate bucket of water, because they have been touched by someone who—as far as her grandmother is concerned—is impure. “For drinking, washing and so on,” she explains, “I have to fetch a separate supply of water for myself”.

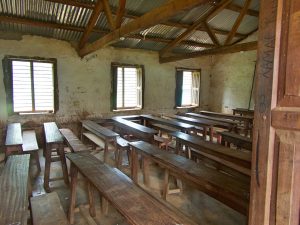

A secondary school classroom in the village of Gutu, Surkhet District, where Sunita lives

When Sunita returns home from school, she goes straight back into the chhau goth, because she is forbidden from entering the family home. “Sometimes my friends, mother or sister keep me company”, she says. “I also help my mother around the house, but I don’t have to do any heavy tasks because she takes care of them.” Sunita realizes that her mother consciously reduces her workload, regardless of whether she is menstruating or not, to give her as much time as possible to study and read. Other girls in her village are not as fortunate and have to carry heavy loads (including water, firewood and fodder), walk long distances and care for dozens of goats, oxen or buffaloes every day—even after nights of exhaustion and poor sleep spent in a chhau goth.

The road Sunita takes to walk to school

Sunita is grateful to her mother for taking on more work to give her all the time she needs to progress at school, but equally disappointed that she has not been convinced by the arguments Sunita has raised with her for ending chhaupadi. “This practice is bad, it leaves me feeling unsafe and vulnerable”, she explains. Nevertheless, she remains hopeful that one day her parents will listen to her and stop forcing her into the chhau goth. After all, she reasons, other girls in the village are being allowed to sleep indoors, slowly but surely. It will only be a matter of time.

Posted By Caroline Armstrong Hall (Nepal)

Posted Jul 13th, 2018

4 Comments

iain

July 13, 2018

This is really great, in that it explains the impact of chhaupadi on the girls. (Not so great when you think of what it must be like in these sheds….) You make Sunita come to life. We need to know the human cost of this practice and really look forward to future blogs and profiles. That will help us to get a good sense of the challenge and start thinking solutions. You’re off to a great start!

Corinne Cummings

July 13, 2018

Hi Caroline, I appreciated your blog post–thank you for sharing Sunita Dhugana’s story. It’s incredible to hear how ingrained this cultural practice is in western Nepal. I am wondering how one could even begin tackling such a loaded issue. It’s great that you had the opportunity to interview Sunita Dhugana and that you will gradually share more stories like hers. Since reading a view articles regarding this cultural practice, I am curious how the younger generation of women within these communities honestly feels about their banishment during menstruation. I would like to hear what young men think too. Do most the young women question this cultural practice and only continue due to the pressure from their elders? I look forward to learning more from you and any other work that you delve into while in Nepal. In addition, I took a look at your Flikr album–you captured excellent photos. I will be on the lookout for more! Good luck with the rest of your journey, Caroline. Best, Corinne

Princia Vas

July 16, 2018

Hey Caroline!

Thank you for sharing the impact of chhaupadi on the girls in Nepal through the story of Sunita! I look forward to learning more about your work in Nepal through different stories, pictures and blog post 🙂

Donna J Olson

July 18, 2018

Caroline,

What a wonderful profile! Thank you for bringing a personal light to chhaupadi! I look forward to hearing more girls’ experiences!