After a couple weeks of planning and adjusting to life in Kathmandu, it was time for the trip that Vicky and I had been most looking forward to: traveling to Bardiya. During Nepal’s civil war (1996-2006), the district of Bardiya had the highest concentration of enforced disappearances in all of Nepal, though families throughout the country were affected by these crimes.

Nepal is currently undergoing a phase of transitional justice (TJ), a period of reconstruction and reconciling as the country rebuilds following the war. In the academic world, technical jargon is often used to describe transitional justice, but at its base, TJ is about addressing the needs of people whose lives were disrupted by war, who are too often forgotten in the transitional phase.

In Nepal, primarily men were disappeared,* and many women lost their husbands, brothers, and fathers – their family’s breadwinners – and have endured great economic difficulty alongside their grief. The families affected by the civil war are at the heart of the work we do for the Advocacy Project and we were eager to meet them. We knew that the women’s group we have been hearing about since we signed up for our fellowships live in Bardiya.

Now we just had to get to them.

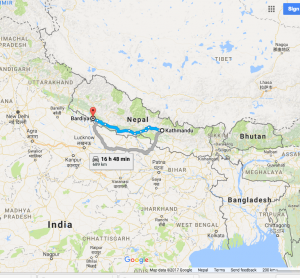

Only two highways pass through Kathmandu, limiting our route options. Our bus would traverse the Naravaangadh-Muglin road, traveling halfway across the country. The journey is expected to take about 17 hours on a good day. We had been warned by friends to expect buses without shock absorbers, extreme potholes and hairpin turns at high altitudes. The route to Bardiya runs South and West and is expected to take about 17 hours on a good day. Luckily, Prabal, our friend and trusty NEFAD partner would be along for the ride. Prabal is a student at Kathmandu University studying Development. One of the great joys of being in Nepal has been working closely with him. He is dedicated to serving other people, eager to learn, and a wonderful colleague. You will be hearing more about him in posts to come.

Prabal, Vicky and I loaded up our backpacks, hauling an additional duffle bag filled with 30 embroidery hoops, to bring to the ladies in the embroidery group, and settled into the bus. Let’s just say our friends’ prophesies about the jarring ride, honking buses, and abrupt twists and turns along cliff edges lived up to their descriptions. Seat belts were generally not functional on the bus, so we bounced our way through the first part of the trip, trying not to look down too frequently out the window.

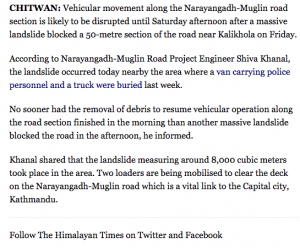

About four hours into the ride, the bus halted abruptly. As we waited, thinking this would be a temporary pause, Vicky received the message you don’t want to see when you are embarking on a 17 hour journey. Scrawled across her phone screen was a headline from one of Kathmandu’s largest newspapers, the Himalayan Times: “Massive landslide blocks Narayaangadh-Muglin road section again.”

The “again” tacked on to the end of that headline hints at the realities of life in Nepal during monsoon season. Even for Nepal, where some landslides are to be expected due to rainy conditions and steep mountainsides along the roads and highways, this landslide was significant enough to make front page news.

After clicking the headline, we realized that there were now 8,000 cubic meters of rubble between us and Bardiya.Not having access to reliable internet, or being able to reach my notebook, I started to record our thoughts as the events unfolded. You can listen to our real time impressions and the background bustle of the bus below:

At this point, the bus cut the engine, the fans, and the air conditioning. We sat, sweltered, and waited. I was most impressed to see mothers and small children waiting out the heat and playing calmly. In the United States, I don’t know if I’ve ever witnessed that kind of patience from kids traveling. After a period, Prabal leaned forward and asked us, “have you ever spent the night on a bus before?” Vicky returned his question with another,

“Are you trying to prepare us?”

To be continued…

*A note on terminology: The action “to be/was/were disappeared” is used in human rights circles to underline the fact that enforced disappearances were not an abstract event, but rather a crime committed by perpetrators.

Click here to donate to our ![]() project for the Bardiya Conflict Victims Cooperative.

project for the Bardiya Conflict Victims Cooperative.

Posted By Kirstin Yanisch (Nepal)

Posted Jul 18th, 2017