Preventing War Rape in DRC

SOSFED works in Fizi Territory, the most underserved of the 9 territories in South Kivu province. Security has been a constant challenge. Two SOSFED centers – at Kikonde and Kazimia – were closed by fighting in 2010 and 2011. In 2012, Mai Mai militia ransacked the Fizi Center and kidnapped an SOSFED field team. For more, visit the SOSFED partner page. SOSFED works in Fizi Territory, the most underserved of the 9 territories in South Kivu province. Security has been a constant challenge. Two SOSFED centers – at Kikonde and Kazimia – were closed by fighting in 2010 and 2011. In 2012, Mai Mai militia ransacked the Fizi Center and kidnapped an SOSFED field team. For more, visit the SOSFED partner page.Read about this campaign in the London Guardian |

For the last four years, AP has partnered with SOS Femmes en Danger (SOSFED), a Congolese NGO, to support survivors of armed sexual violence in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. The program began in 2004 as an act of charity by a group of Congolese women. By 2013, it had evolved into an international campaign. These pages describe the journey.

SOSFED was launched by Marceline Kongolo, a Congolese advocate, to shelter rape survivors while they recover. Marceline has stayed true to this vision, and between 2010 and 2013 the campaign helped 707 survivors to recover at three centers (map). But the campaign also added services as new needs emerged and prepared women for re-entry into society, by teaching them to sew and cultivate. In 2011, SOSFED began to accompany beneficiaries home and help them to reunite with their husbands.

In 2011, the campaign took a major decision. Instead of responding after the fact, SOSFED and AP decided to try to prevent rape. We secured funding from our primary funder, Zivik, to rent fields and install water wells and manioc mills at SOSFED centers. This, we thought, would reduce the time that women spend on the road – and hence their exposure to rape. And so it proved. By the end of 2013, 6,593 families were using the two water wells. Attacks in the Mboko area fell steadily over the four years, and the number of women seeking help from SOSFED fell by half.

AP has supported the campaign in the DRC and from Washington. We have deployed two field officers to work with SOSFED, raised funds, and used the six Ahadi quilts to promote the campaign internationally.

We accompanied Marceline Kongolo to Europe, and hosted her successful visit to the United Nations on March 8, 2012 when she opened an exhibition of advocacy quilts. AP has remained at SOSFED’s side in the years since, offering guidance, outreach and technical support as described on these pages.

As 2014 opens, the endless war in South Kivu may finally be on the wane. The Congolese army is prosecuting rapists. Many Mai Mai fighters, who remain outside the law and are among the most brutal rapists, appear ready to lay down their arms. The fighting has moved away from the populated areas up into the hills.

65,707 Beneficiaries

Between 2010 and 2013, SOSFED assisted 707 survivors of armed sexual violence at its four centers (Kikonde, Kazimia, Mboko, and Fizi Town). An estimated 65,000 villagers used SOSFED’s risk-reduction services in 2013. |

But these gains could quickly be reversed. And even if the threat of war rape diminishes, women will still be exposed to sexual violence in their communities on a daily basis. SOSFED will try to apply what it has learned to this larger and deeper challenge.

Marceline Kongolo founded SOSFED in 2003 after losing her father, brother and grandfather to fighting in the province of Maniema. Marceline’s mother brought her surviving children east and Marceline opened a first center in the village of Kazimia for women and girls, with encouragement from a group of professional women. Marceline has guided SOSFED through its expansion. She has enormous credibility with women because of her own experience and charisma, which were on display during a visit to the UN in March 2012 (above). |

After the past five years, SOSFED is well placed to respond. It can follow the fighting and establish more centers, depending on the need. It can work with village chiefs (Mwami) to promote women’s rights in their villages. It can push the envelope of human rights, and work with new partners like the National Endowment for Democracy and American Bar Association in Washington, to claim legal redress.

Internationally, the campaign will argue that risk reduction should be tested in other conflicts areas, and that modest development interventions can increase protection against war rape. That does not, of course, relieve us of the obligation to stop the war itself. Throughout, the campaign has been generously funded by the Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations through its sister agency Zivik in Berlin; by the Government of Liechtenstein; and by generous private donors. The National Endowment for Democracy has helped SOSFED build on the foundation laid by the program. Many other partners have provided assistance. We thank them all.

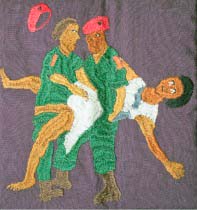

These pages should be read in conjunction with the partner page on SOSFED, and the Ahadi quilt pages. Over 100 women made embroidered squares for the quilts when they were staying at the Mboko and Kikonde centers in 2010. The squares were assembled in the US into quilts which have been widely shown in Europe and North America.

These pages were posted in December 2014.

The Challenge of Sexual Violence in Fizi Territory

|

War rape as seen by the victim: Ecasa M is one of many Congolese rape survivors who embroidered a panel for the Ahadi quilts while recovering at an SOSFED center. Click here for profiles |

SOSFED works in Fizi Territory, one of nine territories in the province of South Kivu and one of the areas in eastern Congo most affected by rape. Fizi attracted international attention after troops from the Congolese Army went on a rampage in Fizi Town on January 1, 2011, under the command of Colonel Kibibi, and raped scores of women. Many of the survivors sought refuge at an SOSFED center.

Fizi Territory has remained deeply threatening to women ever since. Mai Mai militia have terrorized the population (and ransacked two SOSFED centers) and government services are minimal. Yet, in spite of the clear need, Fizi has been shunned by the international community, because of the security risk and poor infrastructure. One UN official described Fizi as “empty.”

War and Sexual Violence

The challenge of armed sexual violence in Fizi is closely linked to the tense relationship between Rwanda and the DRC. Over two million Rwandans fled to the Congo after the genocide in 1994. Many had participated in the genocide, and in 1997 Rwanda invaded Zaire (as the Congo was then called) in an effort to chase them down. Congolese civilian died in their thousands, but a hard core of Hutu genocidaires formed a new militia (FDLR), and fled deep into the brush. Here they seized control of minerals and other resources and began to prey on local communities and women. Rebels from Burundi (FNL) also sought refuge in the Congo and imposed their will in pockets of territory bordering Lake Tanganyika.

AP began working with SOSFED in 2009. The Congolese Army (FARDC) was in the middle of a major operation to track down the FDLR rebels, known as Kimia 2, but Congolese soldiers were ill-disciplined and wreaked havoc on the local population. Most of the women who sought assistance at SOSFED centers in 2010 and 2011 were raped by government troops.

In 2011, a new threat to women began to emerge. It came from local defense forces known as the Mai Mai. These fighters are fiercely opposed to Rwanda and resent the influence of Rwandan-speaking Congolese in the DRC government and army. But they are also led by ruthless war lords, whose main aim is money and power.

The largest Mai Mai force in Fizi Territory is headed by a former army officer named Amuri Yakatumba. The Mai Mai Yakatumba have been an intimidating presence throughout the life of this program. In late 2011, Yakatumba’s fighters ambushed a team from SOSFED. The three staffers were stripped, robbed and held captive for three days.

In June 2012, Mai Mai Yakatumba ransacked the SOSFED center in Fizi Town and stole sewing machines, beds and food. Fizi Town became so dangerous that no government officials or international officials were allowed to sleep in the town overnight. Yakatumba overplayed his hand in 2013 and by the end of the year he had fled to the hills.

Rape as a Weapon of War

Controversy has raged over whether war rape is a deliberate strategy of war, designed to break the spirit of communities. The evidence from Fizi is mixed. Acts of mass rape are certainly calculated and “strategic.” But AP and SOSFED analyzed case files in 2010 and found that most women were attacked when they were fetching water or alone in the fields. In other words, these rapes were opportunistic, rather than planned. It is clear that any woman from a different tribal group will likely be attacked if she is found alone. Militia groups lack a formal structure of command, so such acts cannot be described as a “policy.” But they are most certainly deliberate, and to all intents, strategic.

|

But his troops remain disaffected and could regroup at any moment. Meanwhile, policy-makers continued to debate the motive of the rapists and ask whether war rape is a deliberate strategy (box).

Seeking shelter: Rape survivors at the SOSFED center in Fizi Town. Seeking shelter: Rape survivors at the SOSFED center in Fizi Town. |

Savage Impact

Every woman who seeks shelter from SOSFED has gone through her own hell. Vumi, 25, told her story shortly after arriving at the SOSFED center in Fizi Town. She was one-month pregnant when she was attacked by four men in uniform while returning from market. She passed out and lay unconscious for most of the night. The following morning she made her way to a local health center. She then returned to her home in Fizi and told her husband, who immediately abandoned her. The same evening she felt pains coming and went to the Fizi hospital, where she miscarried. The hospital asked Vumi for $50 to cover the cost of her operation.

Rape survivors are charged $50 by the cash-strapped Fizi hospital. |

Such is the violence of rape that many women, like Vumi, need immediate medical treatment. The response is inadequate. Agencies offer an emergency “morning after” pill against pregnancy, and treatment against STDs, in the form of a so-called “PEP kit.” But this pill must be taken within 72 hours and many victims are too ashamed to seek help for days and even weeks. Ironically, many of the PEP kits distributed by agencies are unused and have to be destroyed.

Congolese health facilities are too weak and underfunded to respond to the needs of raped women. During a visit in August 2012, AP and SOSFED found that the Fizi hospital lacked running water, electricity, and even a means to dispose of medical waste. The hospital’s only income came from patients like Vumi, who were suffering and impoverished.

Psychological Scars

Rape leaves its victims with a deep feeling of self-loathing and shame. As one survivor, Maombi, told AP’s Walter James in one video interview in 2011: “We are something to get rid of.” This is particularly true of SOSFED beneficiaries, who were all abandoned by their husbands after they were attacked.

Commentators often talk of the “stigma” that comes from rape in Congolese society, but SOSFED has found that most of its beneficiaries feel more stigmatized after they are deserted by their husbands. After Justine was attacked, her husband accused her of being with other men while pretending to farm. Regine, another survivor, says that her husband left her because he was worried that that she had contracted a disease. Recovery, for Justine and Regine, means being reunited with their husbands.

Some survivors women have to deal with the added trauma of impregnation during a rape. Out of the 112 women taken in by SOSFED in 2013, seven were impregnated by their attackers. Abortion is strictly taboo in the DRC and not an option. But the women were also prevented from keeping their children by pressure from other villagers, and were forced to give the babies over for adoption (box).

There is even a question about identification. Many agencies insist on the confidentiality of rape victims, and worry that they will be re-traumatized and even

The Youngest Victims

Children born of rape are one of war’s saddest casualties. Seven of the 130 women who sought protection at SOSFED in 2013 were impregnated by their attackers. This left them with an agonizing choice, between bringing up children that were conceived in violence and giving the babies over to adoption. Even if they had wanted to keep the children, they would have been ostracized by other villagers. As a result, the babies joined the huge pool of Congolese orphans. Abortion is illegal and socially reviled in the DRC. |

if they go public. SOSFED and AP have found no evidence of this. Indeed, SOSFED’s beneficiaries have been almost desperate to tell their story. This is not only their right – it is also therapeutic.

Data failure

It is difficult to measure the extent of sexual violence in the eastern DRC because the international community has retreated from any centralized data collection. Between 2003 and 2008, the DRC country office of the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) collected data under its country program. This produced some useful estimates, and also prompted the Congolese government to pass a new law on rape.

In 2008, the UN peace-keeping operation (MONUC, later MONUSCO) took over international coordination of sexual violence. This diluted UNFPA’s focus and energy. UNFPA continued to collect data and serve as the UN focal point, but ran up against resistance from NGOs which refused to share data. Congolese NGOs like SOSFED tried to report to UNFPA but had little incentive because they received no feedback on how their data was used.

Discouraged, UNFPA handed over to the Congolese government in 2012. This has further undermined data collection because the government has been unwilling to publicize data that could embarrass its own soldiers and provides few details. The lack of a credible focal point for data collection hampers efforts to create a coordinated response among NGOs and leads to distorted reporting by the UN. Thus, the UN Security Council was able to confirm only 167 cases of war rape in South Kivu in 2011, and 244 in 2012. This is a clear under-estimate, totally lacking in credibility. None of SOSFED’s data or cases were included.

Legal Impunity

Justice can play an important role in helping women to recover from rape, and seeking legal recourse is a fundamental right. But Congolese have little confidence in their legal system, which is rarely accessible to the poor and imposes hidden fees. Survivors of sexual violence have additional reasons to be concerned. None of SOSFED’s beneficiaries have been able to identify their assailants (who often use fake uniforms). In addition, they fear that working with a lawyer might invite unwelcome publicity. Until 2013, SOSFED’s own staff shared these concerns. They have recently begun to reconsider, and SOSFED hopes to work with the American Bar Association, which has a team in Uvira, to help survivors submit legal complaints.

The UN Response

Throughout the four years of this campaign, SOSFED and AP worked alongside the largest UN peace-keeping operation in the world. MONUSCO is credited with bringing some stability to the Kivus and its presence has probably prevented full-scale war. A special UN intervention force certainly helped to suppress the M23 rebellion in September 2013. But this massive UN presence has also done little to reduce or prevent sexual violence in Fizi Territory, beyond distributing mobile phones near UN military bases. MONUSCO soldiers have been reluctant to intervene for fear of starting hostilities, and never respond to one-off attacks against women. MONUSCO’s ability to investigate is also limited by a shortage of helicopters and strict security rules.

Equally worrying, UN officials have begun to express doubts about the overall seriousness of sexual violence and ask whether it has been exaggerated by NGOs to appeal to donors. MONUSCO does, however, have an effective and committed unit on sexual violence in Bukavu.

In the face of so many different challenges, Congolese women have to fall back on their advocates, like SOSFED, and their own powers of recovery. It is unreasonable to expect them to address the root cause of sexual violence – namely the lawlessness and lack of discipline. But can they change their own behavior so as to reduce their exposure to rape? This has emerged as the chief focus for the campaign by SOSFED and AP, in the DRC and internationally.

Rehabilitation

I Fear Nothing: this video by AP is a tribute to Congolese women. |

SOSFED’s approach to war rape differs from others who work with survivors in South Kivu. Instead of trying to heal the “psychosocial” wounds, SOSFED provides a physical shelter where a woman can be free from the pressures of family life, draw comfort from other women who have gone through a similar experience, and learn a skill.

After three months, SOSFED accompanies the survivor home. The campaign does not assume she has recovered – and indeed, it may be that no one ever fully recovers from war rape. But she will have recovered her confidence and her ability to function as a member of society.

As this video shows, Congolese women have to be strong and resilient.

SOSFED opened a first center for women in the village of Kazimia, in 2004. Three more centers followed, in Kikonde, Mboko and Fizi Town. Between 2010 and 2013, the centers cared for 707 survivors.

SOSFED centers provide a space where survivors can rest, take comfort in the company of other women, and receive services. Centers also prepare survivors for the stress of re-entry into society. SOSFED centers provide a space where survivors can rest, take comfort in the company of other women, and receive services. Centers also prepare survivors for the stress of re-entry into society. |

SOSFED offers different services, starting with three cooked meals a day and a bed. Staff are trained to provide counseling, but this is not SOSFED’s speciality and seriously traumatized women are referred to other organizations with greater expertise. In general, SOSFED firmly believes that recovery is best achieved by being in the company of other women and by being active. This philosophy comes directly from Marceline Kongolo, who has herself suffered great loss within her own family. She says: “If a woman feels worthless, as she does after rape, the solution is to restore her sense of self-worth.” Rebuilding a survivor’s confidence helps her to re-enter society and even to recover.

SOSFED makes sure that beneficiaries are busy from the moment they arrive. Starting in 2010, the campaign has rented fields near the centers where beneficiaries can work the land together, plant manioc and vegetables, and collect the harvest. This builds friendships as well as skills, and provides a sense of accomplishment. SOSFED also offers training in cooking and preparing food, particularly manioc. Sewing is another skill that is both therapeutic and useful.

Medical Care

SOSFED is not a health specialist and has little option but to refer sick women to the local hospital or health center – even though these facilities are often in disrepair and underfunded. In an effort to ensure that all beneficiaries are at least seen by a doctor, and pump some money into the local health system, the campaign offered to cover the cost of a medical check-up in 2013. Seriously ill women were referred to the emergency hospital in Baraka, run by Medecins Sans Frontieres.

Even this encountered obstacles. Some women were afraid to meet with a doctor, in case they had contracted HIV-AIDS and this became known publicly. The hospitals, meanwhile, refused to take money directly from SOSFED for fear that this would affect their government subsidy. In spite of the challenges, 90 women received a medical check-up and treatment in 2013.

Conjugal Visits

Family visits were also introduced in 2013. SOSFED continued to insist that only women (and babies) can stay at a center, but the women become increasingly anxious as the time approaches for them to return home, and a short visit from family members – or a husband – is proof that they will be welcomed home. Sixty-eight such visits were made in 2013.

Giving survivors the chance to seek legal redress speeds their recovery, but as noted earlier justice is not yet part of SOSFED’s toolkit. Few victims are able to identify their attackers and village women have little confidence in the justice system. At the same time, women also understand that their rights have been violated and on at least one occasion in 2011 women in Mboko went en masse to the local army base demanding an end to the attacks.

In 2013, emboldened by the availability of information and the growing number of prosecutions, several women approached the Fizi center in 2013 seeking legal advice. SOSFED has approached the local affiliate of the American Bar Association, which offers legal assistance in South Kivu. Working through village chiefs, the two partners hope to help women lodge complaints in 2014.

When all is said and done, no one can say whether survivors of war rape ever fully recover from such a devastating experience. A better question, in the view of SOSFED, is whether the women can re-enter society with confidence. All of the services described on this page have this aim.

Sewing as Therapy

Sewing was introduced at SOSFED centers in 2010, when beneficiaries produced embroidered squares for the Ahadi quilt project. Many of the women had never sewn before, but they found the experience comforting and were pleased by their handiwork. Demand for sewing increased after Anna McGuire, a high school student in the US, donated $500 for the purchase of two sewing machines. These are used for training. Two local tailors provide basic instruction, and courses are open to all women from the community – 98 took advantage in 2013. Beneficiaries take the skill back when they return home. One group of returnees has even purchased their own machine. Click here for a video on Ahadi quilts Click here to meet the Ahadi quilters |

Reintegration

|

Preparing to return: Mmunga Selemani, one of two SOSFED reintegration officers, advises women at the Fizi Center before they leave for home. Mmunga and his colleagues accompany survivors and work with village chiefs to ease their re-entry. |

Most of the women who seek shelter with SOSFED were spurned by their husbands after being attacked, and ostracized by other villagers. Helping them to recover means helping them to reunite with their husbands. This may be hard for western feminists to accept, but it is a central fact of Congolese life.

In one typical case, a 38-year old woman was raped by three armed men in her fields. After the incident, her husband banished her from the home and left to work in the mines. Before leaving, he said he would probably find another wife. The woman stayed with her aunt for two months, rarely venturing outside, and became an object of derision in the village. After hearing about SOSFED from the radio, she sought shelter at the Mboko center. Even in the center, however, her anxiety increased as the time came for her to return home. She worried that other villagers would think she had spent the three months working as a prostitute at an army camp.

Faced by such cases, the program decided in 2011 to hire reintegration officers to accompany the women back home. Each returnee would also receive $20 to invest. Between 2011 and 2013 reintegration officers Wilondja Lubunga (in Mboko) and Mmunga Selamani (Fizi Town) travelled hundreds of miles and conducted countless sessions with estranged couples and village chiefs.

This process begins the moment a woman arrives at a center, still shell-shocked from her ordeal. Once they know where she lives Mmunga or Wilondja will depart by foot, bicycle or motorbike for her village. Here they meet with the woman’s family, husband, and neighbors. If they find resentment or resistance to the woman’s return, they will consult with the village chief. They will then return with the woman when it comes time for her to go home.

Reintegration is one of the program’s most successful components. Of the 112 women who returned home in 2013, only four were still separated from their husbands at the end of the year. The overall success rate between 2010 and 2013 was over 98%.

Support from the Chief

Village chiefs, known as Mwami, have been central to the success of the campaign and it is one of SOSFED’s great achievements to have coopted and motivate these powerful local leaders. AP met with several chiefs during an evaluation mission in 2012, and found them to be highly sensitive to the damage done by rape.

Many traditional leaders have been personally exposed to sexual violence, and this gives them a further incentive to help. Mwacha Malisho Felix said that his own wife had been raped by rebels from Burundi several years earlier. He understood that victims of rape are not to blame, and that helping them also helps their families and village.

Lukozi Anzolone, the deputy Mwami of Kaseke village, was happy to intervene after one of his villagers, Nyasa, returned home from the Fizi center and ran into trouble with her husband. Initially, the man remained at Nyasa’s side, but he then began to drink and swear at her. Swearing turned to violence and after two weeks, he abandoned his family.

Mwami Anzolone knew that Nyasa’s situation was precarious because she had eight children. But he also had an additional incentive, in that he was related to Nyasa’s husband.

Hail to the Mwami

Village chiefs like Asalo Bilengane, 74, the Mwami of Lukongo village, play a key role in helping rape survivors reintegrate. A public display of support from a Mwami can restore a survivor’s social standing and put pressure on unreasonable husbands. SOSFED has build a friendship with 15 Mwami, and hopes to work with them to combat domestic violence and seek legal redress for survivors. |

Mwami Anzolone was still trying to win Nyasa’s husband around when our AP mission departed the village. We also learned later that the Mwami had allocated three plots of farming land for Nyasa and her friends. Chiefs dispose of all public land in their village, and this makes them particularly important to widows, divorcees and survivors of SGBV.

Investing in Return

Ebunga Asende, the Mwami of Lusenda Katungulu village, remembers opening his door to a woman who was covered in blood. She had been attacked in the fields and crawled down the mountain. The chief counseled 14 couples in the first six months of 2012 and was so concerned at the increasing reports of sexual violence that he has personally forbidden women in the village to farm alone. He has also helped SOSFED beneficiaries like Therese (photo) to find appropriate land when they return. Ebunga Asende, the Mwami of Lusenda Katungulu village, remembers opening his door to a woman who was covered in blood. She had been attacked in the fields and crawled down the mountain. The chief counseled 14 couples in the first six months of 2012 and was so concerned at the increasing reports of sexual violence that he has personally forbidden women in the village to farm alone. He has also helped SOSFED beneficiaries like Therese (photo) to find appropriate land when they return. |

In an effort to ease their reintegration, SOSFED asks all women to join or form a farming group when they return home. Most women own a small plot of family land, and the group will works on one plot after another. This approach has the double advantage of providing protection and labor. In addition, working with other women builds the confidence of rape survivors, because it indicates they are welcomed back into society. One survivor, Nyasa, from Kaseke village, linked up with three other women. She said she had “trained” the women to work together and expressed gratitude to Mwami Anzalone, who found them three small parcels of land.

All returnees after 2011 received $20 when they departed SOSFED for home. This small grant provides a financial cushion for re-entry. When she talked to AP and SOSFED, Justine from Sebele had not yet been reunited with her husband (a fisherman) and was trying to fill the gap left by his sales. She put her $20 towards renting land. Teresa, from the village of Lusenda/Katungulu, used her $20 grant to rent farming land. Regine, in Sebele village, purchased 30 liters of cooking oil and then resold it in smaller quantities, thus earning a small profit. Nyasa, in Kaseke, who had been abandoned by her drunken husband, used her $20 grant to buy and sell charcoal. Nyasa needed the money badly. Her eight children were all studying at school, at a cost to Nyasa of $40 a month.

Risk Reduction

SOSFED’s campaign against war rape uses small development interventions to help women reduce their exposure to sexual violence, while they are recovering at a center and after they return home. This strategy originated from a rough survey of SOSFED beneficiaries that was conducted by AP and SOSFED at the centers in 2010. The survey found that most of the women had been attacked when they traveling alone to fetch wood or water, or when they were working in the fields. Every time they left home there was a risk that they would run into an army patrol or group of militia.

Based on this finding, the program decided to bring several essential services – cultivation, water, fuel, and food processing – to the women. The results have been encouraging. Between 2010 and 2013 only one of SOSFED’s 707 beneficiaries was attacked while staying at a center or after returning home. Equally encouraging, the services have allowed thousands of women living close to the centers to avoid back-breaking, risky travel.

To the Fields

The story begins with agriculture. Almost all of SOSFED’s beneficiaries come from farming communities, and in 2009 SOSFED rented some fields near Mboko where they could cultivate while staying at the center. Initially, it was a free-for-all. Some of the women even got into fights. But the 2010 survey also suggested a reason to persevere. If women were being attacked when they went out alone into the fields to cultivate, why not give them the chance to cultivate together and in security?

Does Risk Reduction Work?

It is hard to prove conclusively that the interventions described on this page have reduced sexual violence, but the evidence is encouraging. Around 6,500 women used the four main risk-reduction services in 2013 and drastically reduced their travel. By 2013, attacks against women had fallen sharply around the Mboko center and some notorious villages experienced no attacks during 2013. The number of women seeking shelter at SOSFED shelters halved between 2010 and 2013. |

The program tested this theory out in 2010 by renting ten hectares of land at Mboko. Around half of the women agreed to participate and earned $26 each from the food they grew. The following year, 2011, the project rented 40 hectares and made cultivation mandatory. All 170 beneficiaries took part and planted vegetables, beans, yams, sweet potatoes and manioc. The land was rich and yielded three harvests for the vegetables, and one for manioc (the staple food). The women kept or sold 70% of the produce for their families, and gave the rest to the SOSFED centers for cooking.

Field work: 130 women grew food in security at SOSFED centers in 2013. They then took the practice back home. By year’s end, over 300 village women were cultivating together alongside former SOSFED beneficiaries. |

This outcome was so encouraging that the program rented the same amount of land in 2012, and again in 2013. By now, the benefits were plain to see. Communal farming kept the women busy and safe. It taught them how to cultivate. It produced a prodigious amount of food – 147,500 kilos in 2013 alone. Finally, it helped to spread the message of risk reduction among surrounding villages. SOSFED gave each woman $20 on condition that she formed or joined a farming group on her return.

Inevitably strains appeared. As news of the program spread, several local women demanded to be included at the Fizi Center and threatened to destroy produce if they were refused. SOSFED’s center managers admitted 15 local women in 2013, but then decided not to give into the blackmail. A vicious blight, known as mosaic, attacked the 2013 manioc crop, but SOSFED’s local friends found money for pesticide. The rising cost of land made it hard to find land close to the centers, but SOSFED’s German donor agreed to carry the extra cost. As each challenge was met, it looked more and more likely that agriculture would remain at the heart of risk reduction.

Fresh Water

The next risk reduction service was water. Until August 2011, fresh water was in short supply in Mboko. Fresh water was shipped in an available at several taps, but it was expensive and ran out quickly. This forced women to draw water from the nearby lake, which was heavily polluted, or walk up to 20 kilometers in search of fresh water. As well as back-breaking, this exposed them to attack on the roads.

The well in Mboko will protect women in the area by reducing the distance traveled to retrieve water. |

The campaign sought and received approval from Zivik, our German donor, to install a water well at Mboko. SOSFED’s dynamic program manager Amisi Mas drew up a contract with a technical organization (ACTED) and oversaw construction of the well during the summer of 2011 with support from Peace Fellow Walter James. Walter and Amisi watched with pride as the local village chief inaugurated the well by sprinkling beer around the new pump, according to tradition.

Within days, the well was being used by hundreds of local families and women from the SOSFED center. The demand was such that SOSFED closed the well for several hours a day to preserve the water table. A team of seven villagers from the neighborhood watched over the pump and ensured that the queues were orderly. This has preserved the pump from breaking down (the normal fate of wells in this area.)

The Mboko well proved so successful that the program built a second well at the Fizi Center in September 2013. The Fizi well opened – on schedule and under budget – to much the same fanfare and the event was covered by four local radio stations. As at Mboko, SOSFED selected a small group of volunteers to monitor the pump and its use.

6,693 families drew water from SOSFED wells in 2013. |

Alternative Cooking Fuel

The third risk reduction intervention addressed the need for cooking fuel. Women in Fizi Territory face two options. They can buy charcoal, which sells for about $10 a sack – way beyond the means of most families. Or they can go out into the forests and collect firewood. As the 2010 survey found, collecting wood exposes women to attack (not to mention its impact on deforestation).

The campaign responded by developing an alternative fuel. Peace Fellow Ned Meerdink worked with a visionary local environmentalist, Clement Kitambala, to produce cooking brickettes from agricultural waste. Clement built a strange-looking contraption which mashed the waste into a pulp. The pulp was then shaped into brickettes and dried. Ned’s video of the process has been translated into Swahili and is one of the most-watched videos in AP’s library.

SOSFED tested out the new fuel in the two centers that were open at the time – Mboko and Kikonde. The Kikonde center closed in 2011 because of security, but many of the former beneficiaries continued to meet at Kikonde and kept the brickette-maker. About 170 survivors formed a cooperative to produce brickettes, which they sold to Tanzania on the other side of the lake.

Meanwhile, in Mboko, SOSFED staff found that the coals burned up before food was properly cooked. They considered converting the portable iron stoves (known as bombolas) that were used for cooking, but decided this would be too expensive. So they asked Clement to design a cheap new stove made of bricks and clay that could be built into the floor and use the new fuel. By the end of 2013, several villages near Mboko had almost completely converted to the new fuel.

300 families cooked with alternative fuel in 2013. |

Fizi Town proved more difficult, because the trade in wood charcoal was both lucrative and controlled by the local military. Each sack of charcoal sold for about $11 – which was the equivalent of two weeks’ pay for the average soldier. After one government official in Fizi Town publicly applauded SOSFED for promoting the new fuel, the man received threats. But Mboko suggests that the new fuel has a future.

Manioc

By 212 the program was helping survivors to grow food, cook food and draw fresh water, in security and within easy reach of their homes. It was time to consider food processing. Manioc (also known as cassava) is a versatile staple food, but it has to go through many stages before it can reach the dinner table. Manioc is planted early in the year, harvested in December, left to dry in the fields for several weeks, and then milled into flour.

This final stage – milling – is time-consuming, expensive and even dangerous. Women can grind the manioc themselves, which is back-breaking work, or they can take their manioc to have it ground into flour at a manioc mill. Prior to 2012, there were two manioc mills in Mboko, and both kept kept 12% of the manioc they processed as a fee. This forced many women to travel long distances in search of a better price. As with the search for water and wood, this exposed them to attack.

By the end of 2013, 1,600 families were using the manioc mill at Mboko. A second mill has been purchased for the Fizi Center. |

Applying the logic of risk reduction, the campaign purchased a manioc mill in 2011. Once installed next to the Mboko center it proved an instant attraction. Customers were charged a fee of only 4% to cover the cost of fuel and pay for the salaries of four guards (who included 3 rape survivors).

Information

The fifth and final piece of the risk reduction strategy is information. This began on a modest note in 2011 when AP and SOSFED listed ten ways to avoid attack, and printed these out on several posters which were placed strategically on the road to Mboko.

After posters, the campaign turned to radio. Congolese get their information through radio, and several local stations reached an audience of thousands. The campaign received a boost when Mr Jack, a popular deejay, coined a song about SOSFED which became an instant hit (photo). Radio Message Du Peuple, in Uvira, then agreed to cover SOSFED’s activities. It was followed by stations in Baraka, Mboko and Fizi Town, and the UN’s Radio Okapi.

In 2013, SOSFED signed an agreement with Radio Bonesha in Burundi, which has tens of thousands of listeners. By the end of the year, six radio stations had produced 53 programs on SOSFED, and program manager Amisi Mas had given 31 interviews. Almost half of the women who sought shelter at SOSFED in 2013 learned of the program through radio, and several women would come by the centers each day seeking advice. Any woman in Fizi Territory who listened to the radio would have heard of SOSFED.

Measuring Impact

Common sense would suggest that this deluge of information, like all of the risk reduction strategies described on this page, has helped to reduce attacks against women. SOSFED’s own data suggests as much. The number of survivors seeking refuge at SOSFED’s two centers fell from 260 in 2010 to 130 in 2013. By 2013 many villages that had been extremely dangerous for women in 2010 were free from violence. (They included the village of Kenya near Mboko, which attracted rapists from Burundi, Rwanda and the Congo in the early years because many families were of mixed ethnicity.)

Sound investment

Mr Jack is one of two Congolese deejays who have produced songs promoting SOSFED and risk reduction. Mr Jack’s jingle can be heard here. At one point, in 2011, it was playing fifteen times a week on several radio stations. Towards the end of 2013 a second deejay, Ganzoliso, penned another song about the program entitled ujumbe (Swahili for “message”). Ujumbe quickly became popular, particularly with children. |

In addition, the women who sought shelter at Mboko in 2013 came from further and further afield, as areas closer to Mboko were pacified. Fizi Town has remained more dangerous and unsettled than Mboko, but even around Fizi Town the data from 2013 suggests a decline in rape.

How much is due to SOSFED’s campaign? Certainly, the retreat of the Mai Mai and better discipline among Congolese troops has helped to reduce violence against women. It is also hard for SOSFED to show cause and effect, because the campaign never produced a baseline survey from which to measure progress. (Most of the risk reduction interventions described on this page were introduced as new needs arose and on an ad hoc basis).

And yet, over 6,000 women were benefitting from SOSFED’s risk reduction interventions by 2013. Whether these women were able to avoid attack as a result is impossible to know, but their lives were certainly less risky for not having to spend several days a month on the road or in the fields. This seems a good reason to invest in risk reduction, while ensuring that future experiments start out with a strong evaluation plan.

International Outreach

On the world stage: Congolese advocates Marceline Kongolo (left) and Chouchou Namegabe received the Fern Holland award from Vital Voices in 2009 at a star-studded ceremony in Washington. Actor Ben Affleck presented the awards. |

The fight against sexual violence is of universal interest and this campaign has worked hard to take the message of risk reduction to an international constituency. Between 2010 and 2013 AP and SOSFED reached out to UN agencies, diplomats, celebrities, NGOs, students, and event quilters.

It began in 2010, when AP nominated Marceline Kongolo for the prestigious Fern Holland award. The award is given out each year to a courageous advocate by Vital Voices at a star-studded ceremony in Washington. After many adventures, Marceline reached Washington the night before the ceremony – her first visit outside the DRC. She appeared on stage with fellow Congolese advocate, ChouChou Namagabe, to receive her award from the actor Ben Affleck (photo).

During her 2010 visit to Washington Marceline met with the US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the designer Diane Von Furstenberg, who has supported SOSFED ever since. The program has donated an advocacy quilt to Ms Von Furstenberg as an expression of appreciation.

Diane Von Furstenberg with the Second Ahadi (Promise) quilt. |

The Ahadi (“promise”) quilts have played a leading role in the international campaign. During the summer of 2010, Peace Fellows helped 120 survivors to produce over a hundred embroidered squares about their lives. The squares were brought back to the US and shared out between two quilting guilds in Michigan and Maryland. By March 2011, the American quilters had produced six striking quilts. In the process, they learned a lot about the pressures facing women in the Congo. As they explain in this video, it came as a shock.

AP took one of the quilts to Geneva in March 2011 for inclusion in an exhibition of quilts at the UN Human Rights Council. The quilt then traveled to Berlin for the tenth anniversary of the Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations (IFA). All six quilts were then shown for the first time at Georgetown University. AP has since exhibited Ahadi quilts at the UN on March 8, 2012, at Kean University, and at the Textile Museum, in Washington, in November 2013. AP took one of the finished quilts back to the DRC in 2012 to be shown at the centers, but it was received with lukewarm interest.

|

At the UN: Margot Wallstrom, the UN Special Representative on Armed Sexual Violence (left) and Marceline Kongolo (center) were keynote speakers at an exhibition of advocacy quilts, held at the UN on March 8, 2012. |

The UN as Partner

The United Nations is a natural partner for SOSFED and the campaign has approached several different members of the UN family inside and outside the DRC. Within the DRC, the two partners have met with the office of the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) in Kinshasa and Bukavu and with human rights officials from MONUSCO, to encourage the UN to collect data more systematically. So far, this has not been successful, but the effort will continue.

The program has had more success in the United States and Europe. AP invited Marceline kongolo to the US in 2012, to open a major exhibition of advocacy quilts at the United Nations on march 8, 2012. Marceline appeared on the stage alongside Dr. Babatunde Osotimehin, the UNFPA Executive Director, Margot Wallstrom, the UN’s Special Representative on Armed Sexual Violence, and the deputy American ambassador. Two Ahadi quilts featured in the exhibition, which was viewed by an estimated 80,000 visitors.

AP has since met with Ms Wallstrom’s successor, Zainab Hawa Bangura, in New York, and briefed senior UN officials who work on armed sexual violence at the UN in New York. Given its global reach, the UN is best placed to help other advocates learn from SOSFED, and replicate the model of risk reduction.

|

Weaving a friendship: Marceline Kongolo met Anna McGuire, 12, on a visit to the US in 2012. Anna, 12, raised $500 to buy sewing machines for SOSFED. |

Embassies and Universities

The campaign has reached out to governments and embassies, including USAID and the US State Department in Washington; the Embassies of the DRC, Germany, the Netherlands, the UK in Washington; and the German embassies in New York and Bamako (Mali). Late in 2013, AP received a special visit from Her Excellency Aurelia Frick, the Foreign Minister of Liechtenstein, on her way to the UN General Assembly (photo). Liechtenstein has supported the program generously since 2012.

Universities are also receptive to SOSFED’s message. The issue of sexual violence is generally too harsh to appeal to high schools, although Anna McGuire, from the Pyle School in Washington, was 13 when she raised $500 on a webpage to send two sewing machines to SOSFED in 2012. Marceline Kongolo met with Anna during her visit to the US in March 2012 (photo). Older students have responded with passion and interest. Bianca DiPersio, 21, organized a fundraiser at the University of Massachusetts in Lowell which raised $2,000. Students have exhibited the Ahadi quilts at an event on campus rape at the University of Virginia, and at Wisconsin University.

Ministerial visit: Ambassador Claudia Fritsche (second from left) and Her Excellency Aurelia Frick, Foreign Minister of Liechtenstein, visited the AP office in Washington in September 2013 for a briefing on risk reduction in the DRC. Liechtenstein has supported SOSFED since 2012. |

Finally, there are the friends – ordinary people who are inspired by Marceline Kongolo’s dignity and message. They have ranged from celebrities like Dianne Von Furstenberg, to Louis Leroux, a French Canadian who met Marceline and was instantly converted. Louis passed away from cancer in 2013, but not before he had raised hundreds of dollars for SOSFED in Canada and drawn French Canadians to SOSFED’s Facebook pages. Marceline was devastated at the news.

The Challenge Ahead

Looking to the future, AP will continue to explore new avenues for promoting SOSFED’s model. In February 2014, AP briefed officials at the World Bank as part of an effort to secure the support of aid agencies for risk reduction. AP will also enlist the support of law schools and the American Bar Association, to help SOSFED integrate justice into the program. AP will take the model of risk reduction to Mali, where hundreds of women were raped after the war in 2012. And of course, the search for funds goes on: SOSFED is fortunate to have a generous Board and many Congolese friends, but the bulk of its funding will likely come from abroad for a long time to come.

The Campaign Team

A score of dedicated individuals have worked for this campaign since 2010, in the Congo and in the US.

In the DRC, the core SOSFED team has remained relatively unchanged over the four years. Marceline Kongolo, who launched SOSFED in 2003, has remained president and in overall charge. Marceline is the public face of the organization, and as such she deals with donors.

Marceline also manages money, with help from two accountants (Julie Nzgire, followed by Anny Konga). Together they have collected and filed hundreds of receipts from all corners of the region.

Amisi Mas, SOSFED’s program manager, coordinates the field team, makes sure that the centers at Mboko and Fizi are supplied, manages offshoot activities like communal farming and sewing, and collects material for donor reports. Amisi is probably the busiest man in the campaign, and arguably its most indispensable member. He has boundless energy and never turns down a challenge, whether it be transporting sand by boat for the Mboko water well or securing visas for AP Peace Fellows.

Bakombwa Djuma works from SOSFED’s liaison office in Baraka, and coordinates activities at the two centers of Mboko and Fizi, with help from Dorkas Nyassa. Mariamu Bashishibe runs the Mboko center with help from Chamalungu Nabeshi and Lubunga Wilondja, one of SOSFED’s two repatriation officers. Mariamu formerly worked for Women to Women International and is a talented seamstress. She drew on her skills for the Ahadi quilt project.

Sangho Laliya ran the Kikonde center until it was closed down in 2011. Sangho then moved to Fizi Town in early 2012 to manage SOSFED’s new center. Soigne Mwenyimali served as her deputy before leaving the team in 2013.

Amisi Mas in a Hurry

Amisi Mas Awi, SOSFED’s program manager, arrived in Uvira from his home country, Kenya, in 2003 just as Marceline and her family arrived from Maniema. He may be the perfect field officer for such a difficult working environment. As brave as he is energetic, Amisi has survived motorcycle accidents and detention by the feared Mai Mai leader Yakatumba. Amisi’s network of contacts stretches far and wide. As an enthusiastic follower of Facebook, he also manages SOSFED’s social media. In 2013, Amisi trained village chiefs under a project funded by the National Endowment for Democracy. Next to Marceline, he most admires SOSFED’s Board of directors. |

Mmunga Selemani also followed Sangho from Kikonde, to serve as her repatriation officer. In addition to this core team, several other SOSFED part-time employees and volunteers deserve special mention. They include Kimongo Djuma, the chauffeur. Jonathan Mussa, who helps Amisi post content to the SOSFED Facebook page; and Naombe Baruani, a local artist, who helped survivors design their squares for the Ahadi quilts. Others will be added to this page as their details become available.

http://www.advocacynet.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Picture-2.png

AP Support for the Campaign

Four Peace Fellows played a key role in helping AP to launch the campaign from the US and manage it during the early years. Ned Meerdink opened the door in 2008 (box) and did two tours as a Peace Fellow, in 2008 and 2009. Ned helped to design AP’s proposal to Zivik in 2009. After Zivik funding came through in 2010, he served as AP’s field officer under January 2011.

Walter James also served as a Peace Fellow in Uvira in 2010. A fluent French-speaker who had worked in Senegal, Walter volunteered as a Peace Fellow at Arche d’Alliance, a Congolese NGO that supported mobile legal clinics. Like Ned, he was attracted by the challenges of working in Uvira and offered to take over as the campaign field officer when Ned pulled out at the end of 2010.

Walter was joined in the summer of 2011 by Peace Fellow Charlie Walker, from the UK. Charlie had worked at Uvira and knew MONUSCO. She was particularly interested in the Ahadi quilt project and worked with the tailor at Uvira to make several sample bags from embroidery. AP later showed the bags to Diane Von Furstenberg, who handed them on to her designer. Charlie also produced strong videos on the Ahadi quilt project and risk reduction.

By 2012 the campaign was running smoothly in the DRC, and there was clearly less need for a full-time field officer from AP. In line with policy, AP was also scaling down and shifting more funds to SOSFED. After overcoming threats, malaria and typhoid, Walter pulled out at the end of 2011.

In 2011, AP’s Iain Guest took over the campaign at AP. Iain made five field trips to the DRC in 2012 and 2013. Karin Orr managed accounts and made one evaluation trip to Burundi in March 2012.

The First Fellow

|

Other AP associates and friends who have worked on the campaign from Washington include Laura Jones, who posted web pages; Jennica Sehorn and Kelly Payton, who helped with exhibitions; Megan Orr, who edited several videos from footage taken in the DRC; Anna McGuire, who raised money for SOSFED; and Tamara Brunhart at the embassy of Liechtenstein, who helped facilitate her government’s very welcome support for the campaign. Our thanks to them all.

http://www.advocacynet.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/Picture-31.png

Photos

http://www.advocacynet.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/sosfed-300×300.jpg

Videos

Newsletters

Liechtenstein Support For Rape Survivors Offers Hope For Dilapidated Congolese Hospital

War Rape in the Congo – Why the Human Security Report is Wrong

The women who are profiled on these pages either gave permission for their photos to be used or expressly asked that they be identified. All of the women who participated in the Ahadi quilt project provided written authorization.